An American in Paris is a jazz-influenced orchestral piece by American composer George Gershwin first performed in 1928. It was inspired by the time that Gershwin had spent in Paris and evokes the sights and energy of the French capital in the Années folles.

John Towner Williams is an American composer, conductor, pianist and trombonist. Regarded by many as one of the greatest film composers of all time, he has composed some of the most popular, recognizable, and critically acclaimed film scores in cinematic history in a career that has spanned over six decades. Williams has won 25 Grammy Awards, seven British Academy Film Awards, five Academy Awards, and four Golden Globe Awards. With 52 Academy Award nominations, he is the second most-nominated individual, after Walt Disney. In 2005, the American Film Institute selected Williams's score to 1977's Star Wars as the greatest film score of all time. The Library of Congress also entered the Star Wars soundtrack into the National Recording Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

The 20th Annual Grammy Awards were held February 23, 1978, and were broadcast live on American television. They were hosted by John Denver and recognized accomplishments by musicians from the year 1977.

Symphony No. 5 by Gustav Mahler was composed in 1901 and 1902, mostly during the summer months at Mahler's holiday cottage at Maiernigg. Among its most distinctive features are the trumpet solo that opens the work with a rhythmic motif similar to the opening of Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 5, the horn solos in the third movement and the frequently performed Adagietto.

Stewart Armstrong Copeland is an American musician and composer. He was the drummer of the British rock band the Police, has produced film and video game soundtracks and written various pieces of music for ballet, opera and orchestra and is considered the 10th Best Drummer of all time by Rolling Stone Magazine.

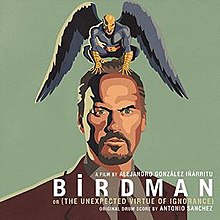

Antonio Sánchez is a Mexican-American jazz drummer and composer best known for his work with jazz guitarist Pat Metheny. In 2014, his popularity increased when he composed an original film score for Birdman, directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu. The soundtrack album was released on October 14, 2014. The score earned him a nomination for the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score and BAFTA Award for Best Film Music; he won the Critics' Choice Movie Award for Best Score and Satellite Award for Best Original Score.

Alejandro González Iñárritu is a Mexican film director, producer, and screenwriter. He is known for telling international stories about the human condition, and his projects have garnered critical acclaim and numerous accolades.

The Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27, is a symphony by the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, written in 1906–07. The premiere was conducted by the composer himself in Saint Petersburg on 8 February 1908. Its duration is approximately 60 minutes when performed uncut; cut performances can be as short as 35 minutes. The score is dedicated to Sergei Taneyev, a Russian composer, teacher, theorist, author, and pupil of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Alongside his Prelude in C-sharp minor, Piano Concerto No. 2 and Piano Concerto No. 3, and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, this symphony remains one of the composer's best known compositions.

Uri Caine is an American classical and jazz pianist and composer.

Unicorn-Kanchana is a British independent record label. Originally known as Unicorn Records, the name Kanchana was added later to distinguish the company from Unicorn Digital of Montréal, Canada which many progressive rock bands like Mystery are signed to. In Hindu and Buddhist mythology, the female name Kanchana means an Apsara, a spirit of the clouds and waters.

The World Soundtrack Awards launched in 2001 by the Film Fest Gent, is aimed at organizing and overseeing the educational, cultural and professional aspects of the art of film music, including the preservation of the history of the soundtrack and its worldwide promotion. The event takes place yearly in Ghent, Belgium with the ceremony usually at the Capitole Concert Hall. Usually, the Brussels Philharmonic conducted by Dirk Brossé performs the awarded music at the ceremony.

Crouch End Festival Chorus (CEFC) is a symphonic choir based in north London which performs in a range of musical styles, including traditional choral repertoire, contemporary classical, rock, pop and film music.

Nigel Westlake is an Australian composer, musician and conductor.

Emily Jordan Bear is an American composer, pianist, songwriter and singer. After beginning to play the piano and compose music as a small child, Bear made her professional piano debut at the Ravinia Festival at the age of five, the youngest performer ever to play there. She gained wider notice from a series of appearances on The Ellen DeGeneres Show beginning at the age of six. She has since played her own compositions and other works with orchestras and ensembles in North America, Europe and Asia, including appearances at Carnegie Hall, the Hollywood Bowl, the Montreux Jazz Festival and Jazz Open Stuttgart. She has won two Morton Gould Young Composer Awards and was the youngest person ever to win the award. She has also won two Herb Alpert Young Jazz Composers Awards.

This is a summary of 2010 in music in the United Kingdom.

Birdman or , or simply Birdman, is a 2014 American black comedy-drama film directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu. It was written by Iñárritu, Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris, Jr., and Armando Bó. The film stars Michael Keaton as Riggan Thomson, a faded Hollywood actor best known for playing the superhero "Birdman", as he struggles to mount a Broadway adaptation of a short story by Raymond Carver. The film also features a supporting cast of Zach Galifianakis, Edward Norton, Andrea Riseborough, Amy Ryan, Emma Stone, and Naomi Watts.

David "Chase" Baird is an American saxophonist, composer and songwriter.

Victor Hernández Stumpfhauser is a Mexican musician and film score composer.

Mike Avenaim, born Michael Avenaim in Sydney, is an Australian-American session drummer, music director, composer, and music producer.

The Revenant: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack is a soundtrack album for the 2015 film, The Revenant, composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alva Noto with additional music by Bryce Dessner. It was released digitally on December 25, 2015, and on CD on January 8, 2016 by Milan Records.