Cheminformatics refers to the use of physical chemistry theory with computer and information science techniques—so called "in silico" techniques—in application to a range of descriptive and prescriptive problems in the field of chemistry, including in its applications to biology and related molecular fields. Such in silico techniques are used, for example, by pharmaceutical companies and in academic settings to aid and inform the process of drug discovery, for instance in the design of well-defined combinatorial libraries of synthetic compounds, or to assist in structure-based drug design. The methods can also be used in chemical and allied industries, and such fields as environmental science and pharmacology, where chemical processes are involved or studied.

Quantitative structure–activity relationship models are regression or classification models used in the chemical and biological sciences and engineering. Like other regression models, QSAR regression models relate a set of "predictor" variables (X) to the potency of the response variable (Y), while classification QSAR models relate the predictor variables to a categorical value of the response variable.

Chemical space is a concept in cheminformatics referring to the property space spanned by all possible molecules and chemical compounds adhering to a given set of construction principles and boundary conditions. It contains millions of compounds which are readily accessible and available to researchers. It is a library used in the method of molecular docking.

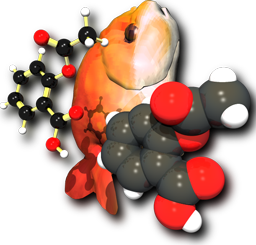

In the field of molecular modeling, docking is a method which predicts the preferred orientation of one molecule to a second when a ligand and a target are bound to each other to form a stable complex. Knowledge of the preferred orientation in turn may be used to predict the strength of association or binding affinity between two molecules using, for example, scoring functions.

PubChem is a database of chemical molecules and their activities against biological assays. The system is maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), a component of the National Library of Medicine, which is part of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH). PubChem can be accessed for free through a web user interface. Millions of compound structures and descriptive datasets can be freely downloaded via FTP. PubChem contains multiple substance descriptions and small molecules with fewer than 100 atoms and 1,000 bonds. More than 80 database vendors contribute to the growing PubChem database.

A structural analog, also known as a chemical analog or simply an analog, is a compound having a structure similar to that of another compound, but differing from it in respect to a certain component.

Open Babel is a free chemical informatics software designed to facilitate the conversion of Chemical file formats and manage molecular data. It serves as a chemical expert system, widely used in fields such as cheminformatics, molecular modelling, and computational chemistry. Open Babel provides both a comprehensive library and command-line utilities, making it a versatile tool for researchers, developers, and professionals.

Molecule mining is the process of data mining, or extracting and discovering patterns, as applied to molecules. Since molecules may be represented by molecular graphs, this is strongly related to graph mining and structured data mining. The main problem is how to represent molecules while discriminating the data instances. One way to do this is chemical similarity metrics, which has a long tradition in the field of cheminformatics.

ISIS/Draw was a chemical structure drawing program developed by MDL Information Systems. It introduced a number of file formats for the storage of chemical information that have become industry standards.

Substructure search (SSS) is a method to retrieve from a database only those chemicals matching a pattern of atoms and bonds which a user specifies. It is an application of graph theory, specifically subgraph matching in which the query is a hydrogen-depleted molecular graph. The mathematical foundations for the method were laid in the 1870s, when it was suggested that chemical structure drawings were equivalent to graphs with atoms as vertices and bonds as edges. SSS is now a standard part of cheminformatics and is widely used by pharmaceutical chemists in drug discovery.

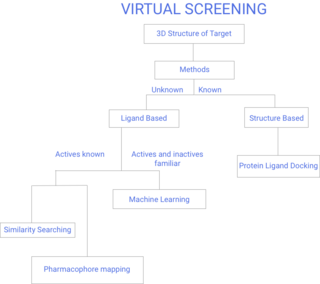

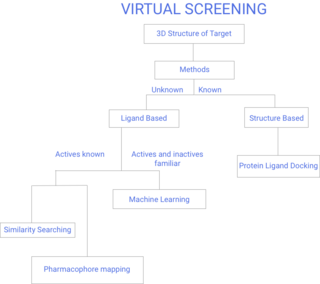

Virtual screening (VS) is a computational technique used in drug discovery to search libraries of small molecules in order to identify those structures which are most likely to bind to a drug target, typically a protein receptor or enzyme.

ChemSpider is a freely accessible online database of chemicals owned by the Royal Society of Chemistry. It contains information on more than 100 million molecules from over 270 data sources, each of them receiving a unique identifier called ChemSpider Identifier.

Druglikeness is a qualitative concept used in drug design for how "druglike" a substance is with respect to factors like bioavailability. It is estimated from the molecular structure before the substance is even synthesized and tested. A druglike molecule has properties such as:

SMILES arbitrary target specification (SMARTS) is a language for specifying substructural patterns in molecules. The SMARTS line notation is expressive and allows extremely precise and transparent substructural specification and atom typing.

Chemical similarity refers to the similarity of chemical elements, molecules or chemical compounds with respect to either structural or functional qualities, i.e. the effect that the chemical compound has on reaction partners in inorganic or biological settings. Biological effects and thus also similarity of effects are usually quantified using the biological activity of a compound. In general terms, function can be related to the chemical activity of compounds.

Antony John Williams is a British chemist and expert in the fields of both nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and cheminformatics at the United States Environmental Protection Agency. He is the founder of the ChemSpider website that was purchased by the Royal Society of Chemistry in May 2009. He is a science blogger and an author.

The ChemDB HIV, Opportunistic Infection and Tuberculosis Therapeutics Database is a publicly available tool developed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to compile preclinical data on small molecules with potential therapeutic action against HIV/AIDS and related opportunistic infections.

Matched molecular pair analysis (MMPA) is a method in cheminformatics that compares the properties of two molecules that differ only by a single chemical transformation, such as the substitution of a hydrogen atom by a chlorine one. Such pairs of compounds are known as matched molecular pairs (MMP). Because the structural difference between the two molecules is small, any experimentally observed change in a physical or biological property between the matched molecular pair can more easily be interpreted. The term was first coined by Kenny and Sadowski in the book Chemoinformatics in Drug Discovery.

A chemical graph generator is a software package to generate computer representations of chemical structures adhering to certain boundary conditions. The development of such software packages is a research topic of cheminformatics. Chemical graph generators are used in areas such as virtual library generation in drug design, in molecular design with specified properties, called inverse QSAR/QSPR, as well as in organic synthesis design, retrosynthesis or in systems for computer-assisted structure elucidation (CASE). CASE systems again have regained interest for the structure elucidation of unknowns in computational metabolomics, a current area of computational biology.

SIRIUS is a Java-based open-source software for the identification of small molecules from fragmentation mass spectrometry data without the use of spectral libraries. It combines the analysis of isotope patterns in MS1 spectra with the analysis of fragmentation patterns in MS2 spectra. SIRIUS is the umbrella application comprising CSI:FingerID, CANOPUS, COSMIC and ZODIAC.