A definition is a statement of the meaning of a term. Definitions can be classified into two large categories: intensional definitions, and extensional definitions. Another important category of definitions is the class of ostensive definitions, which convey the meaning of a term by pointing out examples. A term may have many different senses and multiple meanings, and thus require multiple definitions.

In any of several fields of study that treat the use of signs—for example, in linguistics, logic, mathematics, semantics, semiotics, and philosophy of language—an intension is any property or quality connoted by a word, phrase, or another symbol. In the case of a word, the word's definition often implies an intension. For instance, the intensions of the word plant include properties such as "being composed of cellulose ", "alive", and "organism", among others. A comprehension is the collection of all such intensions.

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are at least two main versions of nominalism. One version denies the existence of universals – things that can be instantiated or exemplified by many particular things. The other version specifically denies the existence of abstract objects – objects that do not exist in space and time.

A syllogism is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

A proposition is a central concept in the philosophy of language, semantics, logic, and related fields, often characterized as the primary bearer of truth or falsity. Propositions are also often characterized as being the kind of thing that declarative sentences denote. For instance the sentence "The sky is blue" denotes the proposition that the sky is blue. However, crucially, propositions are not themselves linguistic expressions. For instance, the English sentence "Snow is white" denotes the same proposition as the German sentence "Schnee ist weiß" even though the two sentences are not the same. Similarly, propositions can also be characterized as the objects of belief and other propositional attitudes. For instance if one believes that the sky is blue, what one believes is the proposition that the sky is blue. A proposition can also be thought of as a kind of idea: Collins Dictionary has a definition for proposition as "a statement or an idea that people can consider or discuss whether it is true."

In logic, extensionality, or extensional equality, refers to principles that judge objects to be equal if they have the same external properties. It stands in contrast to the concept of intensionality, which is concerned with whether the internal definitions of objects are the same.

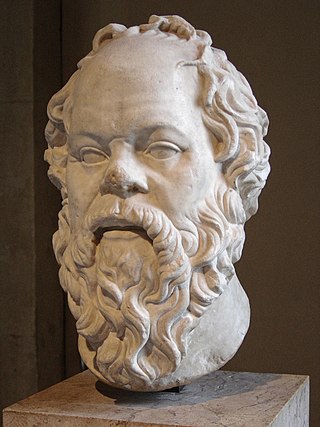

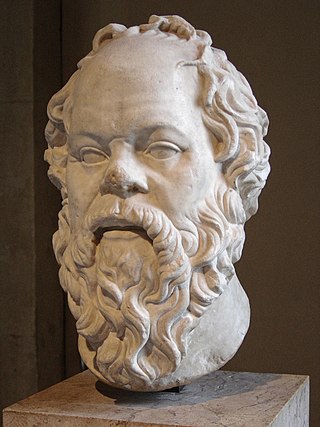

In logic and formal semantics, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly by his followers, the Peripatetics. It was revived after the third century CE by Porphyry's Isagoge.

Intuitionistic type theory is a type theory and an alternative foundation of mathematics. Intuitionistic type theory was created by Per Martin-Löf, a Swedish mathematician and philosopher, who first published it in 1972. There are multiple versions of the type theory: Martin-Löf proposed both intensional and extensional variants of the theory and early impredicative versions, shown to be inconsistent by Girard's paradox, gave way to predicative versions. However, all versions keep the core design of constructive logic using dependent types.

In the philosophy of mathematics, logicism is a programme comprising one or more of the theses that – for some coherent meaning of 'logic' – mathematics is an extension of logic, some or all of mathematics is reducible to logic, or some or all of mathematics may be modelled in logic. Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead championed this programme, initiated by Gottlob Frege and subsequently developed by Richard Dedekind and Giuseppe Peano.

In logic and philosophy, a property is a characteristic of an object; a red object is said to have the property of redness. The property may be considered a form of object in its own right, able to possess other properties. A property, however, differs from individual objects in that it may be instantiated, and often in more than one object. It differs from the logical/mathematical concept of class by not having any concept of extensionality, and from the philosophical concept of class in that a property is considered to be distinct from the objects which possess it. Understanding how different individual entities can in some sense have some of the same properties is the basis of the problem of universals.

Montague grammar is an approach to natural language semantics, named after American logician Richard Montague. The Montague grammar is based on mathematical logic, especially higher-order predicate logic and lambda calculus, and makes use of the notions of intensional logic, via Kripke models. Montague pioneered this approach in the 1960s and early 1970s.

In semiotics, linguistics, anthropology, and philosophy of language, indexicality is the phenomenon of a sign pointing to some element in the context in which it occurs. A sign that signifies indexically is called an index or, in philosophy, an indexical.

The Categories is a text from Aristotle's Organon that enumerates all the possible kinds of things that can be the subject or the predicate of a proposition. They are "perhaps the single most heavily discussed of all Aristotelian notions". The work is brief enough to be divided not into books, as is usual with Aristotle's works, but into fifteen chapters.

In logic, a categorical proposition, or categorical statement, is a proposition that asserts or denies that all or some of the members of one category are included in another. The study of arguments using categorical statements forms an important branch of deductive reasoning that began with the Ancient Greeks.

Logic is the formal science of using reason and is considered a branch of both philosophy and mathematics and to a lesser extent computer science. Logic investigates and classifies the structure of statements and arguments, both through the study of formal systems of inference and the study of arguments in natural language. The scope of logic can therefore be very large, ranging from core topics such as the study of fallacies and paradoxes, to specialized analyses of reasoning such as probability, correct reasoning, and arguments involving causality. One of the aims of logic is to identify the correct and incorrect inferences. Logicians study the criteria for the evaluation of arguments.

Trope denotes figurative and metaphorical language and one which has been used in various technical senses. The term trope derives from the Greek τρόπος (tropos), "a turn, a change", related to the root of the verb τρέπειν (trepein), "to turn, to direct, to alter, to change"; this means that the term is used metaphorically to denote, among other things, metaphorical language.

An interpretation is an assignment of meaning to the symbols of a formal language. Many formal languages used in mathematics, logic, and theoretical computer science are defined in solely syntactic terms, and as such do not have any meaning until they are given some interpretation. The general study of interpretations of formal languages is called formal semantics.

In knowledge representation, a class is a collection of individuals or individuals objects. A class can be defined either by extension, or by intension, using what is called in some ontology languages like OWL. According to the type–token distinction, the ontology is divided into individuals, who are real worlds objects, or events, and types, or classes, who are sets of real world objects. Class expressions or definitions gives the properties that the individuals must fulfill to be members of the class. Individuals that fulfill the property are called Instances.

In logic, extensional and intensional definitions are two key ways in which the objects, concepts, or referents a term refers to can be defined. They give meaning or denotation to a term.