Silphidae is a family of beetles that are known commonly as large carrion beetles, carrion beetles or burying beetles. There are two subfamilies: Silphinae and Nicrophorinae. Nicrophorines are sometimes known as sexton beetles. The number of species is relatively small at around two hundred. They are more diverse in the temperate region although a few tropical endemics are known. Both subfamilies feed on decaying organic matter such as dead animals. The subfamilies differ in which uses parental care and which types of carcasses they prefer. Silphidae are considered to be of importance to forensic entomologists because when they are found on a decaying body they are used to help estimate a post-mortem interval.

A crane fly is any member of the dipteran superfamily Tipuloidea, which contains the living families Cylindrotomidae, Limoniidae, Pediciidae and Tipulidae, as well as several extinct families. "Winter crane flies", members of the family Trichoceridae, are sufficiently different from the typical crane flies of Tipuloidea to be excluded from the superfamily Tipuloidea, and are placed as their sister group within Tipulomorpha.

The apple maggot, also known as the railroad worm, is a species of fruit fly, and a pest of several types of fruits, especially apples. This species evolved about 150 years ago through a sympatric shift from the native host hawthorn to the domesticated apple species Malus domestica in the northeastern United States. This fly is believed to have been accidentally spread to the western United States from the endemic eastern United States region through contaminated apples at multiple points throughout the 20th century. The apple maggot uses Batesian mimicry as a method of defense, with coloration resembling that of the forelegs and pedipalps of a jumping spider.

Fucus is a genus of brown algae found in the intertidal zones of rocky seashores almost throughout the world.

Laminaria is a genus of brown seaweed in the order Laminariales (kelp), comprising 31 species native to the north Atlantic and northern Pacific Oceans. This economically important genus is characterized by long, leathery laminae and relatively large size. Some species are called Devil's apron, due to their shape, or sea colander, due to the perforations present on the lamina. Others are referred to as tangle. Laminaria form a habitat for many fish and invertebrates.

The common green bottle fly is a blowfly found in most areas of the world and is the most well-known of the numerous green bottle fly species. Its body is 10–14 mm (0.39–0.55 in) in length – slightly larger than a house fly – and has brilliant, metallic, blue-green or golden coloration with black markings. It has short, sparse, black bristles (setae) and three cross-grooves on the thorax. The wings are clear with light brown veins, and the legs and antennae are black. The larvae of the fly may be used for maggot therapy, are commonly used in forensic entomology, and can be the cause of myiasis in livestock and pets. The common green bottle fly emerges in the spring for mating.

Eristalis tenax, the common drone fly, is a common, migratory, cosmopolitan species of hover fly. It is the most widely distributed syrphid species in the world, and is known from all regions except the Antarctic. It has been introduced into North America and is widely established. It can be found in gardens and fields in Europe and Australia. It has also been found in the Himalayas.

Hermetia illucens, the black soldier fly, is a common and widespread fly of the family Stratiomyidae. Since the late 20th century, H. illucens has increasingly been gaining attention because of its usefulness for recycling organic waste and generating animal feed.

The Coelopidae or kelp flies are a family of Acalyptratae flies, they are sometimes also called seaweed flies, though both terms are used for a number of seashore Diptera. Fewer than 40 species occur worldwide. The family is found in temperate areas, with species occurring in the southern Afrotropical, Holarctic, and Australasian regions.

Bactrocera dorsalis, previously known as Dacus dorsalis and commonly referred to as the oriental fruit fly, is a species of tephritid fruit fly that is endemic to Southeast Asia. It is one of the major pest species in the genus Bactrocera with a broad host range of cultivated and wild fruits. Male B. dorsalis respond strongly to methyl eugenol, which is used to monitor and estimate populations, as well as to annihilate males as a form of pest control. They are also important pollinators and visitors of wild orchids, Bulbophyllum cheiri and Bulbophyllum vinaceum in Southeast Asia, which lure the flies using methyl eugenol.

Scathophaga stercoraria, commonly known as the yellow dung fly or the golden dung fly, is one of the most familiar and abundant flies in many parts of the Northern Hemisphere. As its common name suggests, it is often found on the feces of large mammals, such as horses, cattle, sheep, deer, and wild boar, where it goes to breed. The distribution of S. stercoraria is likely influenced by human agriculture, especially in northern Europe and North America. The Scathophaga are integral in the animal kingdom due to their role in the natural decomposition of dung in fields. They are also very important in the scientific world due to their short life cycles and susceptibility to experimental manipulations; thus, they have contributed significant knowledge about animal behavior.

Eristalinae are one of the four subfamilies of the fly family Syrphidae, or hoverflies. A well-known species included in this subfamily is the dronefly, Eristalis tenax.

Rhagoletis juglandis, also known as the walnut husk fly, is a species of tephritid or fruit fly in the family Tephritidae. It is closely related to the walnut husk maggot Rhagoletis suavis. This species of fly belongs to the R. suavis group, which has a natural history consistent with allopatric speciation. The flies belonging to this group are morphologically distinguishable.

Coelopa frigida is a species of seaweed fly or kelp fly. It is the most widely distributed species of seaweed fly. It can be found on most shorelines in the temperate Northern Hemisphere. Other species of seaweed flies include Coelopa nebularum and Coelopa pilipes. C. frigida feeds primarily on seaweed, and groups of C. frigida flies tend to populate near bodies of water. Climate change has led to an increase in C. frigida blooms along shores, which creates a pest problem for human beach-goers. C. frigida is also an important organism for the study of sexual selection, particularly female choice, which is influenced by genetics.

Dryomyza anilis is a common fly from the family Dryomyzidae. The fly is found through various areas in the Northern hemisphere and has brown and orange coloration with distinctive large red eyes. The life span of the fly is not known, but laboratory-reared males can live 28–178 days. D. anilis has recently been placed back in the genus Dryomyza, of which it is the type species. Dryomyzidae were previously part of Sciomyzidae but are now considered a separate family with two subfamilies.

Kelp fly is one common name of species of flies in a number of families of "true flies" or Diptera. They generally feed on stranded and rotting seaweed, particularly kelp in the wrack zone. When conditions are suitable they are very numerous and may be ecologically important in the turnover of organic material on the coast. In this role they also may be an important item in the diet of beach-dwelling animals and birds. The flies most generally referred to as kelp flies are the widely distributed Coelopidae, such as Coelopa pilipes. In popular speech however, they are not clearly distinguished from other flies with similar feeding habits, such as the Heterocheilidae, the Helcomyzinae and sundry members of the Anthomyiidae.

Chaetocoelopa littoralis, commonly known as the hairy kelp fly, is a fly of the family Coelopidae. It is endemic to New Zealand and is widely distributed around the coastline, including offshore islands. These flies are black in appearance and show large variation in size, with males tending to be larger and more robust and 'hairy' than females.

Coelopa is a genus of kelp flies in the family Coelopidae. There are about 14 described species in Coelopa.

Cochliomyia macellaria, also known as the secondary screwworm, is a species of blow fly in the family Calliphoridae. These screwworms are referred to as "secondary" because they typically infest wounds after invasion by primary myiasis-causing flies. While blow flies may be found in every terrestrial habitat, C. macellaria is primarily found in the United States, American tropics, and sometimes southern Canada. They are most common in the southeastern United States in states like Florida. C. macellaria have a metallic greenish-blue thorax and a red-orange head and eyes. These adult blowflies range from 5–8 mm in size.

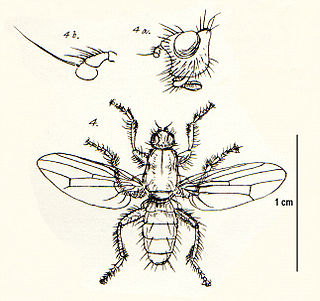

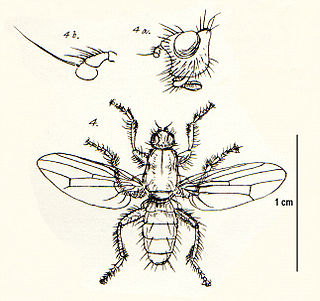

Fucellia maritima is a Palearctic and Nearctic species of kelp fly in the family Anthomyiidae. Adults are found in large numbers from March to September on the British Isles coast. The species is particularly attracted to Fucus sp. and Laminaria sp. seaweed.