Related Research Articles

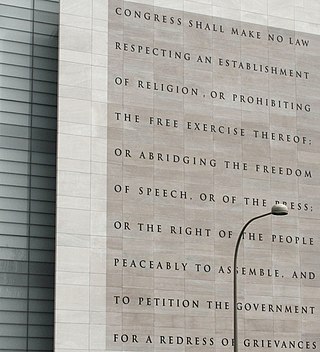

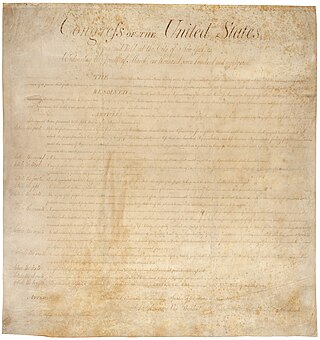

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution prevents Congress from making laws respecting an establishment of religion; prohibiting the free exercise of religion; or abridging the freedom of speech, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly, or the right to petition the government for redress of grievances. It was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights. In the original draft of the Bill of Rights, what is now the First Amendment occupied third place. The first two articles were not ratified by the states, so the article on disestablishment and free speech ended up being first.

In the United States, freedom of speech and expression is strongly protected from government restrictions by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, many state constitutions, and state and federal laws. Freedom of speech, also called free speech, means the free and public expression of opinions without censorship, interference and restraint by the government The term "freedom of speech" embedded in the First Amendment encompasses the decision what to say as well as what not to say. The Supreme Court of the United States has recognized several categories of speech that are given lesser or no protection by the First Amendment and has recognized that governments may enact reasonable time, place, or manner restrictions on speech. The First Amendment's constitutional right of free speech, which is applicable to state and local governments under the incorporation doctrine, prevents only government restrictions on speech, not restrictions imposed by private individuals or businesses unless they are acting on behalf of the government. The right of free speech can, however, be lawfully restricted by time, place and manner in limited circumstances. Some laws may restrict the ability of private businesses and individuals from restricting the speech of others, such as employment laws that restrict employers' ability to prevent employees from disclosing their salary to coworkers or attempting to organize a labor union.

First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, 435 U.S. 765 (1978), is a U.S. constitutional law case which defined the free speech right of corporations for the first time. The United States Supreme Court held that corporations have a First Amendment right to make contributions to ballot initiative campaigns. The ruling came in response to a Massachusetts law that prohibited corporate donations in ballot initiatives unless the corporation's interests were directly involved.

Virginia State Pharmacy Board v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, 425 U.S. 748 (1976), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court held that a state could not limit pharmacists' right to provide information about prescription drug prices. This was an important case in determining the application of the First Amendment to commercial speech.

Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. FCC is the general title of two rulings of the United States Supreme Court on the constitutionality of must-carry regulations enforced by the Federal Communications Commission on cable television operators. In the first ruling, known colloquially as Turner I, 512 U.S. 622 (1994), the Supreme Court held that cable television companies were First Amendment speakers who enjoyed free speech rights when determining what channels and content to carry on their networks, but demurred on whether the must-carry rules at issue were restrictions of those rights. After a remand to a lower court for fact-finding on the economic effects of the then-recent Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act, the dispute returned to the Supreme Court. In Turner II, 520 U.S. 180 (1997), the Supreme Court held that must-carry rules for cable television companies were not restrictions of their free speech rights because the U.S. government had a compelling interest in enabling the distribution of media content from multiple sources and in preserving local television.

Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission, 447 U.S. 557 (1980), was an important case decided by the United States Supreme Court that laid out a four-part test for determining when restrictions on commercial speech violated the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. Justice Powell wrote the opinion of the court. Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. had challenged a Public Service Commission regulation that prohibited promotional advertising by electric utilities. Justice Brennan, Justice Blackmun, and Justice Stevens wrote separate concurring opinions, and the latter two were both joined by Justice Brennan. Justice Rehnquist dissented.

Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 433 U.S. 350 (1977), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld the right of lawyers to advertise their services. In holding that lawyer advertising was commercial speech entitled to protection under the First Amendment, the Court upset the tradition against advertising by lawyers, rejecting it as an antiquated rule of etiquette.

Valentine v. Chrestensen, 316 U.S. 52 (1942), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that commercial speech in public thoroughfares is not constitutionally protected.

44 Liquormart, Inc. v. Rhode Island, 517 U.S. 484 (1996), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that a complete ban on the advertising of alcohol prices was unconstitutional under the First Amendment, and that the Twenty-first Amendment, empowering the states to regulate alcohol, did not lessen other constitutional restraints of state power.

Linmark Associates, Inc. v. Township of Willingboro, 431 U.S. 85 (1977), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States found that an ordinance prohibiting the posting of "for sale" and "sold" signs on real estate within the town violated the First Amendment to the United States Constitution protections for commercial speech.

Bigelow v. Virginia, 421 U.S. 809 (1975), was a United States Supreme Court decision that established First Amendment protection for commercial speech. The ruling is an important precedent on challenges to government regulation of advertising, determining that such publications qualify as speech under the First Amendment.

Posadas de Puerto Rico Associates v. Tourism Co. of Puerto Rico, 478 U.S. 328 (1986), was a 1986 appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States to determine whether Puerto Rico's Games of Chance Act of 1948 is in legal compliance with the United States Constitution, specifically as regards freedom of speech, equal protection and due process. In a 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court held that the Puerto Rico government (law) could restrict advertisement for casino gambling from being targeted to residents, even if the activity itself was legal and advertisement to tourists was permitted. The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the Puerto Rico Supreme Court conclusion, as construed by the Puerto Rico Superior Court, that the Act and regulations do not facially violate the First Amendment, nor did it violate the due process or Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The issue of school speech or curricular speech as it relates to the First Amendment to the United States Constitution has been the center of controversy and litigation since the mid-20th century. The First Amendment's guarantee of freedom of speech applies to students in the public schools. In the landmark decision Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the U.S. Supreme Court formally recognized that students do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate".

Government or state interest is a concept in law that allows the state to regulate a given matter. The concept may apply differently in different countries, and the limitations of what should and should not be of government interest vary, and have varied over time.

Sorrell v. IMS Health Inc., 564 U.S. 552 (2011), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that a Vermont statute that restricted the sale, disclosure, and use of records that revealed the prescribing practices of individual doctors violated the First Amendment.

In the United States, some categories of speech are not protected by the First Amendment. According to the Supreme Court of the United States, the U.S. Constitution protects free speech while allowing limitations on certain categories of speech.

Matal v. Tam, 582 U.S. 218 (2017) is a Supreme Court of the United States case that affirmed unanimously the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit that the provisions of the Lanham Act prohibiting registration of trademarks that may "disparage" persons, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols with the United States Patent and Trademark Office violated the First Amendment.

Hate speech in the United States cannot be directly regulated by the government due to the fundamental right to freedom of speech protected by the Constitution. While "hate speech" is not a legal term in the United States, the U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that most of what would qualify as hate speech in other western countries is legally protected speech under the First Amendment. In a Supreme Court case on the issue, Matal v. Tam (2017), the justices unanimously reaffirmed that there is effectively no "hate speech" exception to the free speech rights protected by the First Amendment and that the U.S. government may not discriminate against speech on the basis of the speaker's viewpoint.

Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court of Ohio, 471 U.S. 626 (1985), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that states can require an advertiser to disclose certain information without violating the advertiser's First Amendment free speech protections as long as the disclosure requirements are reasonably related to the State's interest in preventing deception of consumers. The decision effected identified that some commercial speech may have weaker First Amendment free speech protections than non-commercial speech and that states can compel such commercial speech to protect their interests; future cases have relied on the "Zauderer standard" to determine the constitutionality of state laws that compel commercial speech as long as the information to be disclosed is "purely factual and uncontroversial".

References

- ↑ Central Hudson Gas & Elec. v. Public Svc. Comm'n, 447U.S.557 , 562(1980).

- 1 2 Morrison, Alan B. (2004). "How We Got the Commercial Speech Doctrine: An Originalist's Recollections". Case Western Reserve Law Review. 54 (4): 1189. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ Troy, Daniel (Spring 1998). "Taking Commercial Speech Seriously". Free Speech & Election Law Practice Group Newsletter. 2 (1). The Federalist Society. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ Costello, Sean P. (1997). "Strange Brew: The State of Commercial Speech Jurisprudence before and after 44 Liquormart, Inc. v. Rhode Island". Case Western Reserve Law Review. 47 (2): 681.

- ↑ "Today in 1942: SCOTUS Rules That the First Amendment Doesn't Protect Commercial Speech". Legal Research Blog. Thomson Reuters. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ Bigelow v. Virginia, 421 U.S. 809 (S. Ct., 1975).

- ↑ "Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc. (1976)", The Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in America, Routledge, 2015-04-10, pp. 1003–1004, doi:10.4324/9781315699868-714, ISBN 9781315699868 , retrieved 2021-12-03

- ↑ "Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc. (1976)", The Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in America, Routledge, 2015-04-10, pp. 1003–1004, doi:10.4324/9781315699868-714, ISBN 9781315699868 , retrieved 2021-12-03

- 1 2 Lorillard Tobacco Co. v. Reilly , 533U.S.525 , 572(2001).

- ↑ Central Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Public Serv. Comm'n of NY, 447U.S.557, 566(1980).

- ↑ "Repackaging Zauderer". Harvard Law Review . 130: 972. January 5, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ↑ 44 Liquormart, Inc. v. Rhode Island , 517U.S.484 , 517(1996).

- ↑ Kozinski, Alex; Banner, Stuart (May 1990). "Who's Afraid of Commercial Speech?". Virginia Law Review. 76 (4): 627–653. doi:10.2307/1073208. JSTOR 1073208.

- ↑ Krzeminska-Vamvaka, Joanna (2008). "Freedom of Commercial Speech in Europe". Verlag Dr Kovac, Studien zum Völker- und Europarecht. 58: 292. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1443922. SSRN 1443922.

- ↑ "Barthold v. Germany". Columbia Global Freedom of Expression. Columbia University. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ Council of Europe (March 2007). Freedom of expression in Europe Case-law concerning Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (PDF). Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing. p. 79. ISBN 978-92-871-6087-4 . Retrieved 26 January 2018.