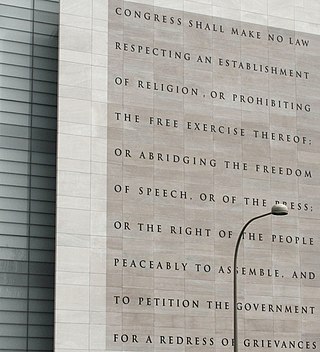

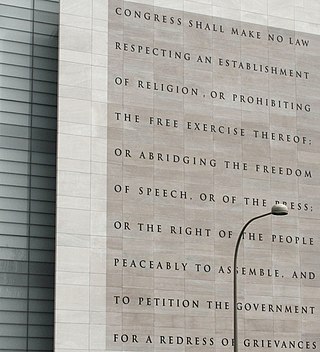

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution prevents Congress from making laws respecting an establishment of religion; prohibiting the free exercise of religion; or abridging the freedom of speech, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly, or the right to petition the government for redress of grievances. It was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights. In the original draft of the Bill of Rights, what is now the First Amendment occupied third place. The first two articles were not ratified by the states, so the article on disestablishment and free speech ended up being first.

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution requires U.S. states to provide attorneys to criminal defendants who are unable to afford their own. The case extended the right to counsel, which had been found under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to impose requirements on the federal government, by imposing those requirements upon the states as well.

Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927), was a United States Supreme Court decision upholding the conviction of an individual who had engaged in speech that raised a clear and present danger to society. While the majority of the Supreme Court Justices voted to uphold the conviction, the ruling has become an important free speech precedent due a concurring opinion by Justice Louis Brandeis recommending new perspectives on criticism of the government by citizens. The ruling was explicitly overruled by Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969.

In the United States, freedom of speech and expression is strongly protected from government restrictions by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, many state constitutions, and state and federal laws. Freedom of speech, also called free speech, means the free and public expression of opinions without censorship, interference and restraint by the government The term "freedom of speech" embedded in the First Amendment encompasses the decision what to say as well as what not to say. The Supreme Court of the United States has recognized several categories of speech that are given lesser or no protection by the First Amendment and has recognized that governments may enact reasonable time, place, or manner restrictions on speech. The First Amendment's constitutional right of free speech, which is applicable to state and local governments under the incorporation doctrine, prevents only government restrictions on speech, not restrictions imposed by private individuals or businesses unless they are acting on behalf of the government. The right of free speech can, however, be lawfully restricted by time, place and manner in limited circumstances. Some laws may restrict the ability of private businesses and individuals from restricting the speech of others, such as employment laws that restrict employers' ability to prevent employees from disclosing their salary to coworkers or attempting to organize a labor union.

First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, 435 U.S. 765 (1978), is a U.S. constitutional law case which defined the free speech right of corporations for the first time. The United States Supreme Court held that corporations have a First Amendment right to make contributions to ballot initiative campaigns. The ruling came in response to a Massachusetts law that prohibited corporate donations in ballot initiatives unless the corporation's interests were directly involved.

Leah Ward Sears is an American jurist and former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia. Sears was the first African-American female chief justice of a state supreme court in the United States. When she was first appointed as justice in 1992 by Governor Zell Miller, she became the first woman and youngest person to sit on Georgia's Supreme Court.

Attorney misconduct is unethical or illegal conduct by an attorney. Attorney misconduct may include: conflict of interest, overbilling, false or misleading statements, knowingly pursuing frivolous and meritless lawsuits, concealing evidence, abandoning a client, failing to disclose all relevant facts, arguing a position while neglecting to disclose prior law which might counter the argument, or having sex with a client.

Watchtower Bible & Tract Society of New York, Inc. v. Village of Stratton, 536 U.S. 150 (2002), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that a town ordinance's provisions making it a misdemeanor to engage in door-to-door advocacy without first registering with town officials and receiving a permit violates the First Amendment as it applies to religious proselytizing, anonymous political speech, and the distribution of handbills.

Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins, 447 U.S. 74 (1980), was a U.S. Supreme Court decision issued on June 9, 1980 which affirmed the decision of the California Supreme Court in a case that arose out of a free speech dispute between the Pruneyard Shopping Center in Campbell, California, and several local high school students.

Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 433 U.S. 350 (1977), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld the right of lawyers to advertise their services. In holding that lawyer advertising was commercial speech entitled to protection under the First Amendment, the Court upset the tradition against advertising by lawyers, rejecting it as an antiquated rule of etiquette.

Florida Bar v. Went For It, Inc., 515 U.S. 618 (1995), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld a state's restriction on lawyer advertising under the First Amendment's commercial speech doctrine. The Court's decision was the first time it did so since Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 433 U.S. 350 (1977), lifted the traditional ban on lawyer advertising.

Moore v. City of East Cleveland, 431 U.S. 494 (1977), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court ruled that an East Cleveland, Ohio zoning ordinance that prohibited Inez Moore, a black grandmother, from living with her grandchild was unconstitutional. Writing for a plurality of the Court, Associate Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. ruled that the East Cleveland zoning ordinance violated substantive due process because it intruded too far upon the "sanctity of the family." Justice John Paul Stevens wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment in which he agreed that the ordinance was unconstitutional, but he based his conclusion upon the theory that the ordinance intruded too far upon Moore's ability to use her property "as she sees fit." Scholars have recognized Moore as one of several Supreme Court decisions that established "a constitutional right to family integrity."

McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission, 514 U.S. 334 (1995), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that an Ohio statute prohibiting anonymous campaign literature is unconstitutional because it violates the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protects the freedom of speech. In a 7–2 decision authored by Justice John Paul Stevens, the Court found that the First Amendment protects the decision of an author to remain anonymous.

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963), is a ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States which held that the reservation of jurisdiction by a federal district court did not bar the U.S. Supreme Court from reviewing a state court's ruling, and also overturned certain laws enacted by the state of Virginia in 1956 as part of the Stanley Plan and massive resistance, as violating the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. The statutes struck down by the Supreme Court had expanded the definitions of the traditional common law crimes of champerty and maintenance, as well as barratry, and had been targeted at the NAACP and its civil rights litigation.

Nevada Commission on Ethics v. Carrigan, 564 U.S. 117 (2011), was a Supreme Court of the United States decision in which the court held that the Nevada Ethics in Government Law, which required government officials recuse in cases involving a conflict of interest, is not unconstitutionally overbroad. Specifically, the law requires government officials to recuse themselves from advocating for and voting on the passage of legislation if private commitments to the interests of others materially affect the official's judgment. Under the terms of this law, the Nevada Commission on Ethics censured city councilman Michael Carrigan for voting on a land project for which his campaign manager was a paid consultant. Carrigan challenged his censure in court and the Nevada Supreme Court ruled in his favor, claiming that casting his vote was protected speech. The Supreme Court reversed, ruling that voting by a public official on a public matter is not First Amendment speech.

In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that solicitation of prospective litigants by nonprofit organizations that engage in litigation as a form of political expression and political association constitutes expressive and associational conduct entitled to First Amendment protection.

Elonis v. United States, 575 U.S. 723 (2015), was a United States Supreme Court case concerning whether conviction of threatening another person over interstate lines requires proof of subjective intent to threaten or whether it is enough to show that a "reasonable person" would regard the statement as threatening. In controversy were the purported threats of violent rap lyrics written by Anthony Douglas Elonis and posted to Facebook under a pseudonym. The ACLU filed an amicus brief in support of the petitioner. It was the first time the Court has heard a case considering true threats and the limits of speech on social media.

Reed v. Town of Gilbert, 576 U.S. 155 (2015), is a case in which the United States Supreme Court clarified when municipalities may impose content-based restrictions on signage. The case also clarified the level of constitutional scrutiny that should be applied to content-based restrictions on speech. In 2005, Gilbert, Arizona adopted a municipal sign ordinance that regulated the manner in which signs could be displayed in public areas. The ordinance imposed stricter limitations on signs advertising religious services than signs that displayed "political" or "ideological" messages. When the town's Sign Code compliance manager cited a local church for violating the ordinance, the church filed a lawsuit in which they argued the town's sign regulations violated its First Amendment right to the freedom of speech.

Packingham v. North Carolina, 582 U.S. 98 (2017), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a North Carolina statute that prohibited registered sex offenders from using social media websites was unconstitutional because it violated the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protects freedom of speech.

California Bankers Assn. v. Shultz, 416 U.S. 21 (1974), was a U.S. Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the Bank Secrecy Act, passed by Congress in 1970 requiring banks to record all transactions and report certain domestic and foreign transactions of high-dollar amounts to the United States Treasury, did not violate the First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution.