Clear and present danger was a doctrine adopted by the Supreme Court of the United States to determine under what circumstances limits can be placed on First Amendment freedoms of speech, press, or assembly. The test was replaced in 1969 with Brandenburg v. Ohio's "imminent lawless action" test.

Fighting words are spoken words directed to the person of the hearer which would have a tendency to cause acts of violence by the person to whom, individually, the remark is addressed. The term fighting words describes words that when uttered inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.

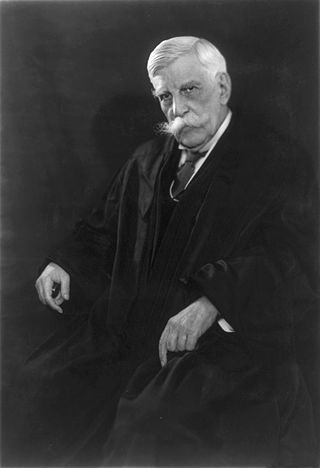

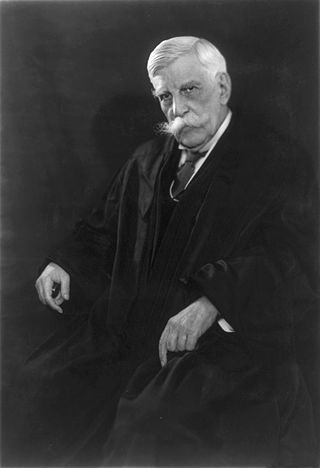

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court concerning enforcement of the Espionage Act of 1917 during World War I. A unanimous Supreme Court, in an opinion by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., concluded that Charles Schenck, who distributed flyers to draft-age men urging resistance to induction, could be convicted of an attempt to obstruct the draft, a criminal offense. The First Amendment did not protect Schenck from prosecution, even though, "in many places and in ordinary times, Schenck, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within his constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done." In this case, Holmes said, "the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent." Therefore, Schenck could be punished.

Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951), was a United States Supreme Court case relating to Eugene Dennis, General Secretary of the Communist Party USA. The Court ruled that Dennis did not have the right under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution to exercise free speech, publication and assembly, if the exercise involved the creation of a plot to overthrow the government. In 1969, Dennis was de facto overruled by Brandenburg v. Ohio.

Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927), was a United States Supreme Court decision upholding the conviction of an individual who had engaged in speech that raised a threat to society. Whitney was explicitly overruled by Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969.

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court holding that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution had extended the First Amendment's provisions protecting freedom of speech and freedom of the press to apply to the governments of U.S. states. Along with Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Co. v. City of Chicago (1897), it was one of the first major cases involving the incorporation of the Bill of Rights. It was also one of a series of Supreme Court cases that defined the scope of the First Amendment's protection of free speech and established the standard to which a state or the federal government would be held when it criminalized speech or writing.

Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States upholding the 1918 Amendment to the Espionage Act of 1917 which made it a criminal offense to urge the curtailment of production of the materials necessary to wage the war against Germany with intent to hinder the progress of the war. The 1918 Amendment is commonly referred to as if it were a separate Act, the Sedition Act of 1918.

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court in which the Court articulated the fighting words doctrine, a limitation of the First Amendment's guarantee of freedom of speech.

"Imminent lawless action" is one of several legal standards American courts use to determine whether certain speech is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. The standard was first established in 1969 in the United States Supreme Court case Brandenburg v. Ohio.

"Shouting fire in a crowded theater" is a popular analogy for speech or actions whose principal purpose is to create panic, and in particular for speech or actions which may for that reason be thought to be outside the scope of free speech protections. The phrase is a paraphrasing of a dictum, or non-binding statement, from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.'s opinion in the United States Supreme Court case Schenck v. United States in 1919, which held that the defendant's speech in opposition to the draft during World War I was not protected free speech under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. The case was later partially overturned by Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969, which limited the scope of banned speech to that which would be directed to and likely to incite imminent lawless action.

Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten, 244 F. 535, was a decision by the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, that addressed advocacy of illegal activity under the First Amendment.

Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315 (1951), was a United States Supreme Court case involving Irving Feiner's arrest for a violation of section 722 of the New York Penal Code, "inciting a breach of the peace," as he addressed a crowd on a street.

In United States law, the bad tendency principle was a test that permitted restriction of freedom of speech by government if it is believed that a form of speech has a sole tendency to incite or cause illegal activity. The principle, formulated in Patterson v. Colorado (1907), was seemingly overturned with the "clear and present danger" principle used in the landmark case Schenck v. United States (1919), as stated by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Yet eight months later, at the start of the next term in Abrams v. United States (1919), the Court again used the bad tendency test to uphold the conviction of a Russian immigrant who published and distributed leaflets calling for a general strike and otherwise advocated revolutionary, anarchist, and socialist views. Holmes dissented in Abrams, explaining how the clear and present danger test should be employed to overturn Abrams' conviction. The re-emergence of the bad tendency test resulted in a string of cases after Abrams employing that test, including Whitney v. California (1927), where a woman was convicted simply because of her association with the Communist Party. The court ruled unanimously that although she had not committed any crimes, her relationship with the Communists represented a "bad tendency" and thus was unprotected. The "bad tendency" test was finally overturned in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) and was replaced by the "imminent lawless action" test.

Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a "breach of peace" ordinance of the City of Chicago that banned speech that "stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, brings about a condition of unrest, or creates a disturbance" was unconstitutional under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.

In the United States, criminal anarchy is the crime of conspiracy to overthrow the government by force or violence, or by assassination of the executive head or of any of the executive officials of government, or by any unlawful means. The advocacy of such doctrine either by word of mouth or writing is a felony in many U.S. states. Circa 1955, the United States Solicitor General said that forty-two States plus Alaska and Hawaii had statutes which in some form prohibited advocacy of the violent overthrow of established government.

In the United States, some categories of speech are not protected by the First Amendment. According to the Supreme Court of the United States, the U.S. Constitution protects free speech while allowing limitations on certain categories of speech.

Advocacy and incitement are two categories of speech, the latter of which is a more specific type of the former directed to producing imminent lawless action and which is likely to incite or produce such action. In the 1957 case Yates v. United States, Justice John Marshall Harlan II ruled that only advocacy that constituted an "effort to instigate action" was punishable.

Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105 (1973), was a United States Supreme Court case involving the First Amendment that reaffirmed and clarified the imminent lawless action test first articulated in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969). Hess is still cited by courts to protect speech threatening future lawless action.

Hate speech in the United States cannot be directly regulated by the government due to the fundamental right to freedom of speech protected by the Constitution. While "hate speech" is not a legal term in the United States, the U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that most of what would qualify as hate speech in other western countries is legally protected speech under the First Amendment. In a Supreme Court case on the issue, Matal v. Tam (2017), the justices unanimously reaffirmed that there is effectively no "hate speech" exception to the free speech rights protected by the First Amendment and that the U.S. government may not discriminate against speech on the basis of the speaker's viewpoint.

Spence v. Washington, 418 U.S. 405 (1974), was a United States Supreme Court case dealing with non-verbal free speech and its protections under the First Amendment. The Court, in a per curiam decision, ruled that a Washington state law that banned the display of the American flag adorned with additional decorations was unconstitutional as it violated protected speech. The case established the Spence test that has been used by the judicial system to determine when non-verbal speech may be sufficiently expressive for First Amendment protections.