An oil refinery or petroleum refinery is an industrial process plant where petroleum is transformed and refined into useful products such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, asphalt base, fuel oils, heating oil, kerosene, liquefied petroleum gas and petroleum naphtha. Petrochemical feedstock like ethylene and propylene can also be produced directly by cracking crude oil without the need of using refined products of crude oil such as naphtha. The crude oil feedstock has typically been processed by an oil production plant. There is usually an oil depot at or near an oil refinery for the storage of incoming crude oil feedstock as well as bulk liquid products. In 2020, the total capacity of global refineries for crude oil was about 101.2 million barrels per day.

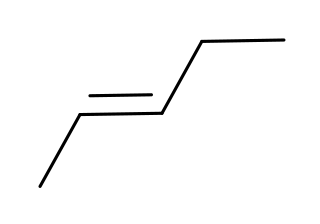

Propylene, also known as propene, is an unsaturated organic compound with the chemical formula CH3CH=CH2. It has one double bond, and is the second simplest member of the alkene class of hydrocarbons. It is a colorless gas with a faint petroleum-like odor.

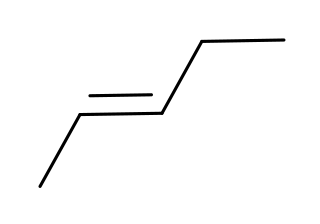

Butene, also known as butylene, is an alkene with the formula C4H8. The word butene may refer to any of the individual compounds. They are colourless gases that are present in crude oil as a minor constituent in quantities that are too small for viable extraction. Butene is therefore obtained by catalytic cracking of long-chain hydrocarbons left during refining of crude oil. Cracking produces a mixture of products, and the butene is extracted from this by fractional distillation.

The Fischer–Tropsch process (FT) is a collection of chemical reactions that converts a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, known as syngas, into liquid hydrocarbons. These reactions occur in the presence of metal catalysts, typically at temperatures of 150–300 °C (302–572 °F) and pressures of one to several tens of atmospheres. The Fischer–Tropsch process is an important reaction in both coal liquefaction and gas to liquids technology for producing liquid hydrocarbons.

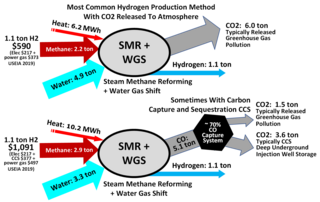

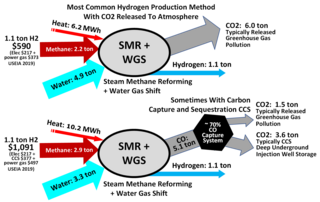

Steam reforming or steam methane reforming (SMR) is a method for producing syngas (hydrogen and carbon monoxide) by reaction of hydrocarbons with water. Commonly natural gas is the feedstock. The main purpose of this technology is hydrogen production. The reaction is represented by this equilibrium:

A visbreaker is a processing unit in an oil refinery whose purpose is to reduce the quantity of residual oil produced in the distillation of crude oil and to increase the yield of more valuable middle distillates by the refinery. A visbreaker thermally cracks large hydrocarbon molecules in the oil by heating in a furnace to reduce its viscosity and to produce small quantities of light hydrocarbons.. The process name of "visbreaker" refers to the fact that the process reduces the viscosity of the residual oil. The process is non-catalytic.

Catalytic reforming is a chemical process used to convert petroleum refinery naphthas distilled from crude oil into high-octane liquid products called reformates, which are premium blending stocks for high-octane gasoline. The process converts low-octane linear hydrocarbons (paraffins) into branched alkanes (isoparaffins) and cyclic naphthenes, which are then partially dehydrogenated to produce high-octane aromatic hydrocarbons. The dehydrogenation also produces significant amounts of byproduct hydrogen gas, which is fed into other refinery processes such as hydrocracking. A side reaction is hydrogenolysis, which produces light hydrocarbons of lower value, such as methane, ethane, propane and butanes.

The Claus process is the most significant gas desulfurizing process, recovering elemental sulfur from gaseous hydrogen sulfide. First patented in 1883 by the chemist Carl Friedrich Claus, the Claus process has become the industry standard.

Pentenes are alkenes with the chemical formula C

5H

10. Each molecule contains one double bond within its molecular structure. Six different compounds are in this class, differing from each other by whether the carbon atoms are attached linearly or in a branched structure and whether the double bond has a cis or trans form.

Fluid Catalytic Cracking (FCC) is the conversion process used in petroleum refineries to convert the high-boiling point, high-molecular weight hydrocarbon fractions of petroleum into gasoline, alkene gases, and other petroleum products. The cracking of petroleum hydrocarbons was originally done by thermal cracking, now virtually replaced by catalytic cracking, which yields greater volumes of high octane rating gasoline; and produces by-product gases, with more carbon-carbon double bonds, that are of greater economic value than the gases produced by thermal cracking.

Hydrodesulfurization (HDS), also called hydrotreatment or hydrotreating, is a catalytic chemical process widely used to remove sulfur (S) from natural gas and from refined petroleum products, such as gasoline or petrol, jet fuel, kerosene, diesel fuel, and fuel oils. The purpose of removing the sulfur, and creating products such as ultra-low-sulfur diesel, is to reduce the sulfur dioxide emissions that result from using those fuels in automotive vehicles, aircraft, railroad locomotives, ships, gas or oil burning power plants, residential and industrial furnaces, and other forms of fuel combustion.

Merox is an acronym for mercaptan oxidation. It is a proprietary catalytic chemical process developed by UOP used in oil refineries and natural gas processing plants to remove mercaptans from LPG, propane, butanes, light naphthas, kerosene and jet fuel by converting them to liquid hydrocarbon disulfides.

A delayed coker is a type of coker whose process consists of heating a residual oil feed to its thermal cracking temperature in a furnace with multiple parallel passes. This cracks the heavy, long chain hydrocarbon molecules of the residual oil into coker gas oil and petroleum coke.

The Penex process is a continuous catalytic process used in the refining of crude oil. It isomerizes light naphtha (C5/C6) into higher-octane, branched C5/C6 molecules. It also reduces the concentration of benzene in the gasoline pool. It was first used commercially in 1958. Ideally, the isomerization catalyst converts normal pentane (nC5) to isopentane (iC5) and normal hexane (nC6) to 2,2- and 2,3-dimethylbutane. The thermodynamic equilibrium is more favorable at low temperature.

William C. Pfefferle was an American scientist and inventor.

Petroleum refining processes are the chemical engineering processes and other facilities used in petroleum refineries to transform crude oil into useful products such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), gasoline or petrol, kerosene, jet fuel, diesel oil and fuel oils.

Petroleum naphtha is an intermediate hydrocarbon liquid stream derived from the refining of crude oil with CAS-no 64742-48-9. It is most usually desulfurized and then catalytically reformed, which rearranges or restructures the hydrocarbon molecules in the naphtha as well as breaking some of the molecules into smaller molecules to produce a high-octane component of gasoline.

In the petroleum refining and petrochemical industries, the initialism BTX refers to mixtures of benzene, toluene, and the three xylene isomers, all of which are aromatic hydrocarbons. The xylene isomers are distinguished by the designations ortho –, meta –, and para – as indicated in the adjacent diagram. If ethylbenzene is included, the mixture is sometimes referred to as BTEX.

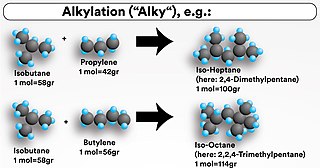

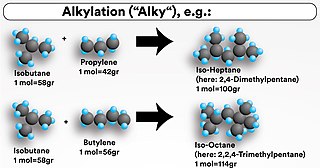

An alkylation unit (alky) is one of the conversion processes used in petroleum refineries. It is used to convert isobutane and low-molecular-weight alkenes (primarily a mixture of propene and butene) into alkylate, a high octane gasoline component. The process occurs in the presence of an acid such as sulfuric acid (H2SO4) or hydrofluoric acid (HF) as catalyst. Depending on the acid used, the unit is called a sulfuric acid alkylation unit (SAAU) or hydrofluoric acid alkylation unit (HFAU). In short, the alky produces a high-quality gasoline blending stock by combining two shorter hydrocarbon molecules into one longer chain gasoline-range molecule by mixing isobutane with a light olefin such as propylene or butylene from the refinery's fluid catalytic cracking unit (FCCU) in the presence of an acid catalyst.

Steam cracking is a petrochemical process in which saturated hydrocarbons are broken down into smaller, often unsaturated, hydrocarbons. It is the principal industrial method for producing the lighter alkenes, including ethene and propene. Steam cracker units are facilities in which a feedstock such as naphtha, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), ethane, propane or butane is thermally cracked through the use of steam in steam cracking furnaces to produce lighter hydrocarbons. The propane dehydrogenation process may be accomplished through different commercial technologies. The main differences between each of them concerns the catalyst employed, design of the reactor and strategies to achieve higher conversion rates.