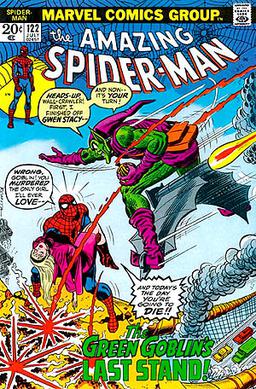

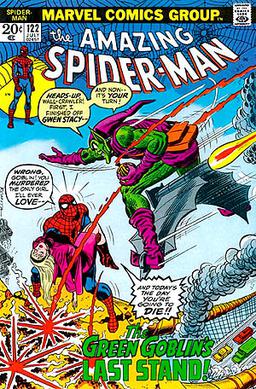

The Silver Age of Comic Books was a period of artistic advancement and widespread commercial success in mainstream American comic books, predominantly those featuring the superhero archetype. Following the Golden Age of Comic Books, the Silver Age is considered to cover the period from 1956 to 1970, and was succeeded by the Bronze Age.

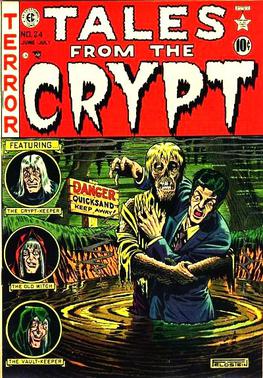

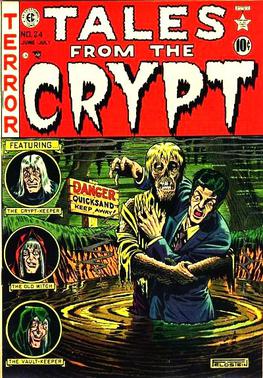

Entertaining Comics, more commonly known as EC Comics, was an American publisher of comic books, which specialized in horror fiction, crime fiction, satire, military fiction, dark fantasy, and science fiction from the 1940s through the mid-1950s, notably the Tales from the Crypt series. Initially, EC was owned by Maxwell Gaines and specialized in educational and child-oriented stories. After Max Gaines' death in a boating accident in 1947, his son William Gaines took over the company and began to print more mature stories, delving into the genres of horror, war, fantasy, science-fiction, adventure, and others. Noted for their high quality and shock endings, these stories were also unique in their socially conscious, progressive themes that anticipated the Civil Rights Movement and the dawn of the 1960s counterculture. In 1954–55, censorship pressures prompted it to concentrate on the humor magazine Mad, leading to the company's greatest and most enduring success. Consequently, by 1956, the company ceased publishing all of its comic lines except Mad.

An American comic book is a thin periodical originating in the United States, on average 32 pages, containing comics. While the form originated in 1933, American comic books first gained popularity after the 1938 publication of Action Comics, which included the debut of the superhero Superman. This was followed by a superhero boom that lasted until the end of World War II. After the war, while superheroes were marginalized, the comic book industry rapidly expanded and genres such as horror, crime, science fiction and romance became popular. The 1950s saw a gradual decline, due to a shift away from print media in the wake of television and the impact of the Comics Code Authority. The late 1950s and the 1960s saw a superhero revival and superheroes remained the dominant character archetype throughout the late 20th century into the 21st century.

The Bronze Age of Comic Books is an informal name for a period in the history of American superhero comic books, usually said to run from 1970 to 1985. It follows the Silver Age of Comic Books and is followed by the Modern Age of Comic Books.

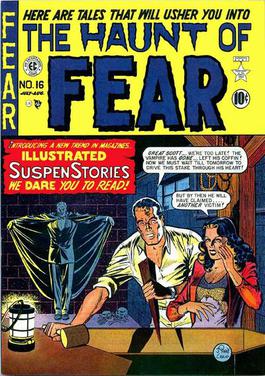

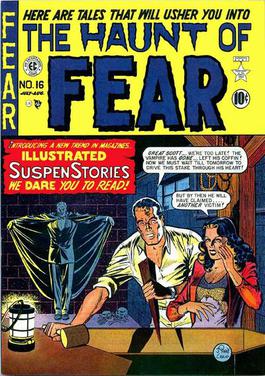

The Haunt of Fear was an American bi-monthly horror comic anthology series published by EC Comics, starting in 1950. Along with Tales from the Crypt and The Vault of Horror, it formed a trifecta of popular EC horror anthologies. The Haunt of Fear was sold at newsstands beginning with its May/June 1950 issue.

Charles Biro was an American comic book creator and cartoonist. He created the comic book characters Airboy and Steel Sterling, and worked on Daredevil Comics and Crime Does Not Pay at Lev Gleason Publications.

Crime SuspenStories was a bi-monthly anthology crime comic published by EC Comics in the early 1950s. The title first arrived on newsstands with its October/November 1950 issue and ceased publication with its February/March 1955 issue, producing a total of 27 issues. Years after its demise, the title was reprinted in its entirety, and four stories were adapted for television in the HBO's Tales From The Crypt.

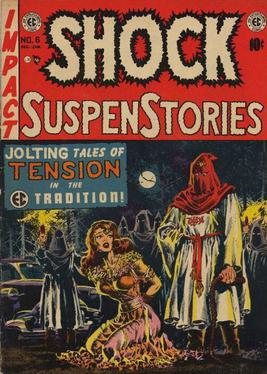

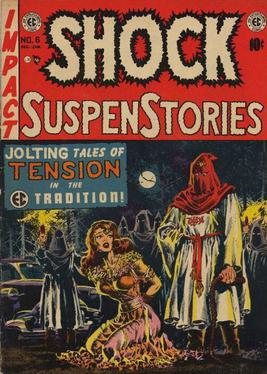

Shock SuspenStories was part of the EC Comics line in the early 1950s. The bi-monthly comic, published by Bill Gaines and edited by Al Feldstein, began with issue 1 in February/March 1952. Over a four-year span, it ran for 18 issues, ending with the December/January 1955 issue.

John Thomas Alexis Craig, was an American comic book artist notable for his work with the EC Comics line of the 1950s. He sometimes used the pseudonyms Jay Taycee and F. C. Aljohn.

George Roussos, also known under the pseudonym George Bell, was an American comic book artist best known as one of Jack Kirby's Silver Age inkers, including on landmark early issues of Marvel Comics' Fantastic Four. Over five decades, he created artwork for numerous publishers, including EC Comics, and he was a staff colorist for Marvel Comics.

Crestwood Publications, also known as Feature Publications, was a magazine publisher that also published comic books from the 1940s through the 1960s. Its title Prize Comics contained what is considered the first ongoing horror comic-book feature, Dick Briefer's "Frankenstein". Crestwood is best known for its Prize Group imprint, published in the late 1940s to mid-1950s through packagers Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, who created such historically prominent titles as the horror comic Black Magic, the creator-owned superhero satire Fighting American, and the first romance comic title, Young Romance.

Blue Ribbon Comics is the name of two American comic book anthology series, the first published by the Archie Comics predecessor MLJ Magazines Inc., commonly known as MLJ Comics, from 1939 to 1942, during the Golden Age of Comic Books. The revival was the second comic published in the 1980s by Archie Comics under the Red Circle and Archie Adventure Series banners.

Crime Does Not Pay is an American comic book series published between 1942 and 1955 by Lev Gleason Publications. Edited and chiefly written by Charles Biro, the title launched the crime comics genre and was the first "true crime" comic book series. At the height of its popularity, Crime Does Not Pay would claim a readership of six million on its covers. The series' sensationalized recountings of the deeds of gangsters such as Baby Face Nelson and Machine Gun Kelly were illustrated by artists Bob Wood, George Tuska, and others. Stories were often introduced and commented upon by "Mr. Crime", a ghoulish figure in a top hat, and the precursor of horror hosts such as EC Comics's The Crypt Keeper. According to Gerard Jones, Crime Does Not Pay was "the first nonhumor comic to rival the superheroes in sales, the first to open the comic book market to large numbers of late adolescent and young males."

Carroll O. Wessler, better known as Carl Wessler, was an American animator of the 1930s and a comic book writer from the 1940s though the 1980s for such companies as DC Comics, EC Comics, Marvel Comics, and Warren Publishing.

Novelty Press was an American Golden Age comic-book publisher that operated from 1940 to 1949. It was the comic book imprint of Curtis Publishing Company, publisher of The Saturday Evening Post. Among Novelty's best-known and longest-running titles were the companion titles Blue Bolt and Target Comics.

The EC Archives are an ongoing series of American hardcover collections of full-color comic book reprints of EC Comics, published by Russ Cochran and Gemstone Publishing from 2006 to 2008, and then continued by Cochran and Grant Geissman's GC imprint (2011–2012), and finally taken over by Dark Horse in 2013.

Horror comics are comic books, graphic novels, black-and-white comics magazines, and manga focusing on horror fiction. In the US market, horror comic books reached a peak in the late 1940s through the mid-1950s, when concern over content and the imposition of the self-censorship Comics Code Authority contributed to the demise of many titles and the toning down of others. Black-and-white horror-comics magazines, which did not fall under the Code, flourished from the mid-1960s through the early 1980s from a variety of publishers. Mainstream American color comic books experienced a horror resurgence in the 1970s, following a loosening of the Code. While the genre has had greater and lesser periods of popularity, it occupies a firm niche in comics as of the 2010s.

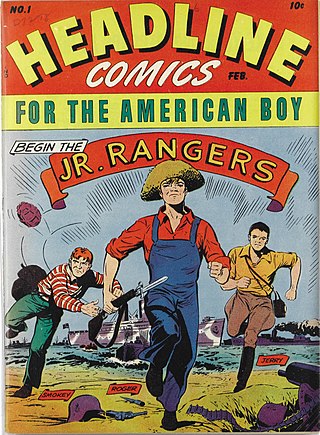

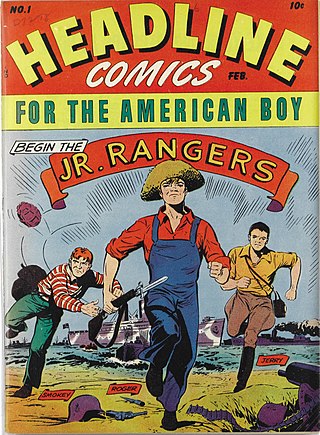

Headline Comics (For The American Boy) was an American comics magazine published by Prize Comics (under the indicia titles American Boys' Comics, Inc. for 21 issues, and Headline Publications, Inc. for 26 issues) from February 1943 – October 1956. The comic was transformed from a boy superhero/adventure title to a crime comic in 1947, with issue #23 (March). The publication became an anthology of the deeds of gangsters and murderers.

Jack Oleck was an American novelist and comic book writer particularly known for his work in the horror genre.

Arnold Book Company (ABC) was a British publisher of comic books that operated in the late 1940s and 1950s, most actively from 1950 to 1954. ABC published original titles like the war comic Ace Malloy of the Special Squadron and the science fiction title Space Comics, and reprints of American horror and crime titles like Adventures into the Unknown, Black Magic Comics, and Justice Traps the Guilty. British contributors to the company's titles include Mick Anglo and Denis Gifford. Arnold Book Company was closely connected to the fellow British comics publisher L. Miller & Son.