Related Research Articles

Revelstoke Dam, also known as Revelstoke Canyon Dam, is a hydroelectric dam spanning the Columbia River, 5 km (3.1 mi) north of Revelstoke, British Columbia, Canada. The powerhouse was completed in 1984 and has an installed capacity of 2480 MW. Four generating units were installed initially, with one additional unit (#5) having come online in 2011. The reservoir behind the dam is named Lake Revelstoke. The dam is operated by BC Hydro.

Andrew Onderdonk was an American construction contractor who worked on several major projects in the West, including the San Francisco seawall in California and the Canadian Pacific Railway in British Columbia. He was born in New York City to an established ethnic Dutch family. He received his education at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

The Canadian Pacific Survey or Canadian Pacific Railway Survey comprised many distinct geographical surveys conducted during the 1870s and 1880s, designed to determine the ideal route of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Although much of the survey's activity focused on locating suitable mountain passes through the Canadian Rockies, Selkirk Mountains, Monashee Mountains, Canadian Cascades and Coast Mountains of western Canada, locating the best route across the rugged terrain of the Canadian Shield north of Lake Superior was also a primary goal. The survey played an important role in the exploration of Canada, especially in the mapping of hitherto-uncharted parts of British Columbia.

Lake Revelstoke or Revelstoke Lake or Revelstoke Lake Reservoir is an artificial lake on the Columbia River, north of the town of Revelstoke, British Columbia and south of Mica Creek. This lake is the reservoir formed by the Revelstoke Dam, which during its construction was also known as the Revelstoke Canyon Dam, inundating the Columbia's canyon in this area and the historic Dalles des Morts and some of the former gold diggings of the Big Bend Gold Rush. The dam's site is at what had been the head of river navigation by steamboat from Northport, Washington via the Arrow Lakes.

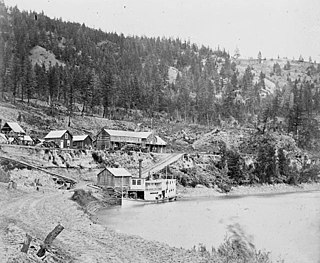

The Big Bend Gold Rush was a gold rush in the Big Bend Country of the Colony of British Columbia in the mid-1860s.

The Enterprise was a passenger and freight sternwheeler that was built for service on the Soda Creek to Quesnel route on the upper Fraser River in British Columbia. It was built at Four Mile Creek near Alexandria by pioneer shipbuilder James Trahey of Victoria for Gustavus Blin Wright and Captain Thomas Wright and was put into service in the spring of 1863. Her captain was JW Doane. The Enterprise was the first of twelve sternwheelers that would work on this section of the Fraser from 1863 to 1921. Though she was not large, she was a wonderful example of the early craft of shipbuilding. All of the lumber she was built from was cut by hand and her boiler and engines had been brought to the building site at Four Mile packed by mule via the wagon road from Port Douglas, 300 miles away.

William Moore was a steamship captain, businessman, miner and explorer in British Columbia and Alaska. During most of British Columbia's gold rushes Moore could be found at the center of activity, either providing transportation to the miners, working claims or delivering mail and supplies.

Many steamboats operated on the Columbia River and its tributaries, in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, from about 1850 to 1981. Major tributaries of the Columbia that formed steamboat routes included the Willamette and Snake rivers. Navigation was impractical between the Snake River and the Canada–US border, due to several rapids, but steamboats also operated along the Wenatchee Reach of the Columbia, in northern Washington, and on the Arrow Lakes of southern British Columbia.

The era of steamboats on the Arrow Lakes and adjoining reaches of the Columbia River is long-gone but was an important part of the history of the West Kootenay and Columbia Country regions of British Columbia Canada. The Arrow Lakes are formed by the Columbia River in southeastern British Columbia. Steamboats were employed on both sides of the border in the upper reaches of the Columbia, linking port towns on either side of the border, and sometimes boats would be built in one country and operated in the other. Tributaries of the Columbia include the Kootenay River which rises in Canada, then flows south into the United States, then bends north again back into Canada, where it widens into Kootenay Lake. As with the Arrow Lakes, steamboats once operated on the Kootenay River and Kootenay Lake.

The sidewheeler Idaho was a steamboat that ran on the Columbia River and Puget Sound from 1860 to 1898. There is some confusion as to the origins of the name; many historians have proposed it is the inspiration for the name of the State of Idaho. Considerable doubt has been cast on this due to the fact that it is unclear if the boat was named before or after the idea of 'Idaho' as a territory name was proposed. John Ruckel also allegedly stated he had named the boat after a Native American term meaning 'Gem of the Mountains' he got from a mining friend from what is now Colorado territory. This steamer should not be confused with the many other vessels of the same name, including the sternwheeler Idaho built in 1903 for service on Lake Coeur d'Alene and the steamship Idaho of the Pacific Coast Steamship Line which sank near Port Townsend, Washington.

The Forty-Nine was a steamboat that operated from the mid-1860s to the early 1870s in today's West Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia.

Boat Encampment is a ghost town in the East Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia. The locality was at the tip of the Big Bend on the north shore of the Columbia River. The general vicinity, on the former Big Bend Highway, was by road about 151 kilometres (94 mi) northwest of Golden and 159 kilometres (99 mi) north of Revelstoke.

Lytton was a sternwheel steamboat that ran on the Arrow Lakes and the Columbia River in southeastern British Columbia and northeastern Washington from 1890 to 1904.

Cottonwood Canyon is a canyon along the Fraser River in the North Cariboo region of the Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It is located west of the Cariboo Mountains on the Fraser River south of its confluence with the east-flowing West Road River and north of its confluence with the northwest-flowing Cottonwood River just northwest of the city of Quesnel, The first European explorer was Simon Fraser (explorer) who ran the rapids on the first of June, 1808. One of his canoes became stranded and had to be pulled out of the canyon with a rope. It was one of the obstacles for gold rush-era steamboats operating on the Fraser from Quesnel to Fort George and up the Nechako and Stuart Rivers to Stuart Lake.

This article covers the water based Canadian canoe routes used by early explorers of Canada with special emphasis on the fur trade.

Voyageurs were 18th- and 19th-century French Canadians who transported furs by canoe at the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places and times where that transportation was over long distances. The voyageurs' strength and endurance was regarded as legendary. They were celebrated in folklore and music. For reasons of promised celebrity status and wealth, this position was coveted.

Saskatchewan River fur trade The Saskatchewan River was one of the two main axes of Canadian expansion west of Lake Winnipeg. The other and more important one was northwest to the Athabasca Country. For background see Canadian canoe routes (early). The main trade route followed the North Saskatchewan River and Saskatchewan River, which were just south of the forested beaver country. The South Saskatchewan River was a prairie river with few furs.

The Pemmican War was a series of armed confrontations during the North American fur trade between the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) and the North West Company (NWC) in the years following the establishment of the Red River Colony in 1812 by Lord Selkirk. It ended in 1821 when the NWC merged with the HBC.

La Porte was a boomtown in British Columbia, Canada, during the Big Bend Gold Rush. The site at the foot of the Dalles des Morts, or Death Rapids, was chosen as the location of a ferry and town on April 23, 1866, during the first voyage of the steamboat Forty-Nine up the Columbia River. The name reflected its role as the gateway to the mines.

References

- 1 2 "Death Rapids: Origin notes and history", BC Geographical Name Information Service Archived 2007-08-15 at archive.today

- ↑ "Steamboats of the Columbia" article in Trails In Time website by Walter Volovsek

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe; William Nemos; Alfred Bates (1887). History of British Columbia, 1792-1887. San Francisco, The History company. p. 533. online at Google Books