| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

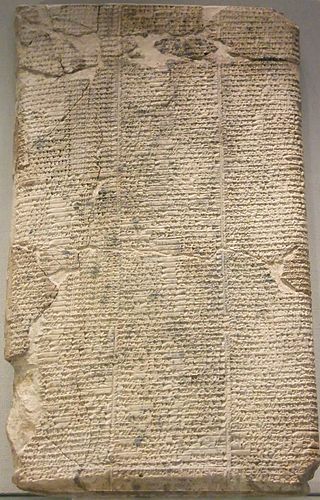

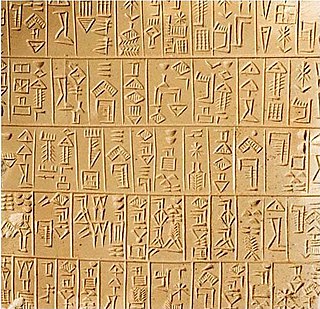

The "Debate between bird and fish" is an essay written in the Sumerian language on clay tablets, dating back to the mid to late 3rd millennium BC. It belongs to the genre of Sumerian disputation.

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

The "Debate between bird and fish" is an essay written in the Sumerian language on clay tablets, dating back to the mid to late 3rd millennium BC. It belongs to the genre of Sumerian disputation.

Six Sumerian disputations are known from Sumerian literature, falling into the literary genre of disputations. Aside from Bird and Fish, other examples include: [1]

These appeared a few centuries after writing was established in Sumerian Mesopotamia. The debates are philosophical and address humanity's place in the world. [2]

The bird and fish debate is a 190-line text of cuneiform script. It begins with a discussion of the gods having given Mesopotamia and dwelling places for humans; for water for the fields, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, and the marshes, marshland, grazing lands for humans, and the birds of the marshes, and fish are all given. The debate then begins starting with Fish addressing Bird. [3]

The initial speech of Fish: [4]

The 2nd and 3rd paragraphs continue:

Bird replies:

Bird continues:

After the initial speech and retort, Fish attacks Bird's nest. Battle ensues between the two of them, in more words. Near the end Bird requests that Shulgi decide in Bird's favor:

Šulgi proclaims:

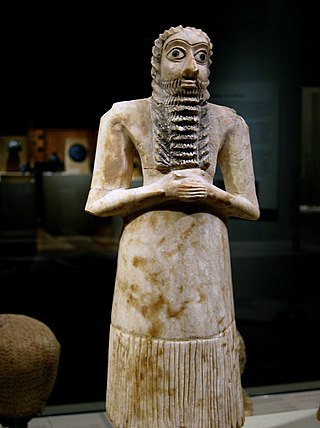

Enlil, later known as Elil and Ellil, is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with wind, air, earth, and storms. He is first attested as the chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon, but he was later worshipped by the Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Hurrians. Enlil's primary center of worship was the Ekur temple in the city of Nippur, which was believed to have been built by Enlil himself and was regarded as the "mooring-rope" of heaven and earth. He is also sometimes referred to in Sumerian texts as Nunamnir. According to one Sumerian hymn, Enlil himself was so holy that not even the other gods could look upon him. Enlil rose to prominence during the twenty-fourth century BC with the rise of Nippur. His cult fell into decline after Nippur was sacked by the Elamites in 1230 BC and he was eventually supplanted as the chief god of the Mesopotamian pantheon by the Babylonian national god Marduk.

Ziusudra of Shuruppak is listed in the WB-62 Sumerian King List recension as the last king of Sumer prior to the Great Flood. He is subsequently recorded as the hero of the Eridu Genesis and appears in the writings of Berossus as Xisuthros.

The Lament for Ur, or Lamentation over the city of Ur is a Sumerian lament composed around the time of the fall of Ur to the Elamites and the end of the city's third dynasty.

Aratta is a land that appears in Sumerian myths surrounding Enmerkar and Lugalbanda, two early and possibly mythical kings of Uruk also mentioned on the Sumerian king list.

Sumerian literature constitutes the earliest known corpus of recorded literature, including the religious writings and other traditional stories maintained by the Sumerian civilization and largely preserved by the later Akkadian and Babylonian empires. These records were written in the Sumerian language in the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC during the Middle Bronze Age.

The Barton Cylinder, also known as CBS 8383, is a Sumerian creation myth, written on a clay cylinder in the mid to late 3rd millennium BCE, which is now in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Joan Goodnick Westenholz suggests it dates to around 2400 BC.

The Gudea cylinders are a pair of terracotta cylinders dating to c. 2125 BC, on which is written in cuneiform a Sumerian myth called the Building of Ningirsu's temple. The cylinders were made by Gudea, the ruler of Lagash, and were found in 1877 during excavations at Telloh, Iraq and are now displayed in the Louvre in Paris, France. They are the largest cuneiform cylinders yet discovered and contain the longest known text written in the Sumerian language.

The "Debate between sheep and grain" or "Myth of cattle and grain" is a Sumerian disputation and creation myth, written on clay tablets in the mid to late 3rd millennium BC.

The Debate between Winter and Summer or Myth of Emesh and Enten is a Sumerian creation myth belonging to the genre of Sumerian disputations, written on clay tablets in the mid to late 3rd millennium BC.

Enlil and Ninlil, the Myth of Enlil and Ninlil, or Enlil and Ninlil: The begetting of Nanna is a Sumerian creation myth, written on clay tablets in the mid to late 3rd millennium BC.

Self-praise of Shulgi is a Sumerian hymn dedicated to the Third Dynasty of Ur ruler Shulgi, written on clay tablets dated to between 2100 and 2000 BC.

The Kesh temple hymn, Liturgy to Nintud, or Liturgy to Nintud on the creation of man and woman, is a Sumerian tablet, written on clay tablets as early as 2600 BCE. Along with the Instructions of Shuruppak, it is the oldest surviving literature in the world.

The Hymn to Enlil, Enlil and the Ekur (Enlil A), Hymn to the Ekur, Hymn and incantation to Enlil, Hymn to Enlil the all beneficent or Excerpt from an exorcism is a Sumerian myth, written on clay tablets in the late third millennium BC.

Enamtila is a Sumerian term meaning "house of life" or possibly "house of creation". It was a sanctuary dedicated to Enlil, likely to have been located within the Ekur at Nippur during the Akkadian Empire. It also referred to various other temples including those to later versions of Enlil; Marduk and Bel as well as one to Ea. It was likely another name for Ehursag, a temple dedicated to Shulgi in Ur. A hymn to Nanna suggests the link "To Ehursag, the house of the king, to the Enamtila of prince Shulgi we go!" Another reference in the Inanna - Dunmuzi text translated by Samuel Noah Kramer references the king's palace by this name and possibly makes references to the "sacred marriage": "In the Enamtila, the house of the king, his wife dwelt with him in joy, in the Enamtila, the house of the king, Inanna dwelt with him in joy. Inanna, rejoicing in his house ...". A fire is reported to have broken out next to the Enamtila in a Babylonian astronomical diary dated to the third century BC. The Enamtila is also referred to as a palace of Ibbi-Sin at Ur in the Lament for Sumer and Ur, "Its king sat immobilised in his own palace. Ibbi-Suen was sitting in anguish in his own palace. In E-namtila, his place of delight, he wept bitterly. The flood dashing a hoe on the ground was levelling everything."

The Song of the hoe, sometimes also known as the Creation of the pickaxe or the Praise of the pickaxe, is a Sumerian creation myth, written on clay tablets from the last century of the 3rd millennium BCE.

The Sumerian disputation poem or Sumerian debate is a genre of Sumerian literature in the form of a disputation. Extant compositions from this genre date to the middle-to-late 3rd millennium BC. There are six primary poems belonging to this genre. The genre of Sumerian disputations also differs from Aesopic disputations as the former contain only dialogue without narration. In their own language, the texts are described as adamin in the doxologies at the end of the poem, which literally means "contests (between) two".

Ur-Ninurta, c. 1859 – 1832 BC or c. 1923 – 1896 BC, was the 6th king of the 1st Dynasty of Isin. A usurper, Ur-Ninurta seized the throne on the fall of Lipit-Ištar and held it until his violent death some 28 years later.

The Debate between tree and reed is a work of Sumerian literature belonging to the genre of disputations poem. It was written on clay tablets and dates to the Third Dynasty of Ur. The text was reconstructed by M. Civil in the 1960s from 24 manuscripts but it is currently the least studied of the disputation poems and a full translation has not yet been published. Some other Sumerian disputations include the dispute between bird and fish, cattle and grain, and Summer and Winter.

The Debate between the hoe and the plough is a work of Sumerian literature and one of the six extant works belonging to this literature's genre of disputations poem. It was written on clay tablets and dates to the Third Dynasty of Ur and runs 196 lines in length. The text was reconstructed by M. Civil in the 1960s. The two protagonists, as in other disputation poems, are two inarticulate things: in this case, two pieces of agricultural equipment, the hoe and the plough. The debate is about which is the better tool.

The Debate between silver and copper is a work of Sumerian literature and one of the six extant works belonging to this literature's genre of disputations poem. It was written on clay tablets and dates to the Third Dynasty of Ur and runs 196 lines in length. The text was reconstructed by M. Civil in the 1960s. Like other Sumerian disputation poems, it features two typically inarticulate things debating over which one is superior.