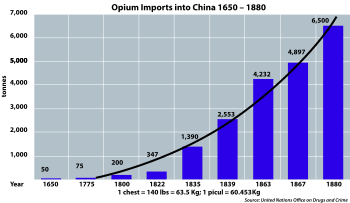

A reduction in import duty by the British government on Chinese tea from 110 per cent to an average of 10 per cent in 1784 caused a surge in domestic demand, which in turn led to a huge silver deficit for the East India Company (EIC), who were the sole importers of the commodity. [2] Silver was the only currency the Chinese would accept in payment for their tea, and to redress the balance in 1793 the EIC acquired a monopoly on opium production in India from the British government. However, as it had been illegal to sell the drug in China since 1800, [3] consignments were sent to Calcutta for auction [4] whereafter private traders smuggled the opium to the southern ports of mainland China. [4] [5]

In 1834 the EIC lost its trading monopoly in China [6] and Lord Napier was appointed as first commissioner of trade for the country. Napier's first visit to the southern port of Canton (now Guangzhou), where the rigid Canton System controlled all trade with China, failed to convince the Chinese authorities to open up further ports for trading. In 1837, the Qing government, having vacillated for a while on the correct approach to the problem of growing opium addiction amongst the people, decided to expel merchant William Jardine of Jardine, Matheson & Co. along with others involved in the illegal trade. Governor-General of Guangdong and Guangxi Deng Tingzhen and the governor of Guangdong along with the Guangdong Customs Supervisor (粵海关部监督) issued an edict to this effect [7] although Jardine remained in the country. Former Royal Navy officer Charles Elliot became Chief Superintendent of British Trade in China in 1838, by which time the number of Chinese opium addicts had grown to between four and twelve million. [8] By the early 19th century, more and more Chinese were smoking British opium as a recreational drug. But for many, what started as recreation soon became a punishing addiction: many people who stopped ingesting opium suffered chills, nausea, and cramps, and sometimes died from withdrawal. Once addicted, people would often do almost anything to continue to get access to the drug. [9] Although some officials argued that a tax on opium would yield a profit for the imperial treasury, the Daoguang Emperor instead decided to stop the trade altogether and severely punish those involved. He then appointed respected scholar and government official Lin Zexu as Special Imperial Commissioner to enforce his will.

Lin and the foreign traders

Any foreigner or foreigners bringing opium to the Central Land, with design to sell the same, the principals shall most assuredly be decapitated, and the accessories strangled; and all property (found on board the same ship) shall be confiscated. The space of a year and a half is granted, within the which, if any one bringing opium by mistake, shall voluntarily step forward and deliver it up, he shall be absolved from all consequences of his crime.

Soon after his arrival in Canton in the middle of 1839, Lin wrote to Queen Victoria in an appeal to her moral responsibility to stop the opium trade. [10] The letter elicited no response (sources suggest that it was lost in transit), [11] but it was later reprinted in the London Times as a direct appeal to the British public. An edict from the Daoguang Emperor followed on 18 March, [12] emphasising the serious penalties for opium smuggling that would now apply.

On 18 March 1839, Lin summoned the twelve Chinese merchants of the Cohong who acted as intermediaries for the foreign opium traders. He told them that all European merchants were to hand over the opium in their possession and cease trading in the drug forthwith. [12] The commissioner went on to call the Cohong "traitors" and accuse them of complicity in the illegal trade; they had three days to persuade the foreigners to forfeit their opium or two of them would be executed and their wealth and lands confiscated. Howqua, the leader of the Cohong passed Lin's orders to the foreign merchants who subsequently convened a meeting of their Chamber of Commerce on 21 March. After the meeting, Howqua was told that Lin's move was a bluff and his threats should be ignored. In fear for his life, the merchant then suggested that surrendering at least some contraband might assuage Lin. Lancelot Dent of Dent & Co. agreed to surrender a small quantity of the drug and others followed suit, even though the amounts offered represented only a tiny fraction of the foreign merchants' total stock, which was worth millions of pounds. [13] The commissioner then backed down on his promise to execute members of the Cohong and instead invited the top foreign merchants including Dent [14] to his residence for interview.

Dent was warned by his friends [15] that in 1774 an individual who had heeded such a summons ended up garroted [16] so he instead asked Howqua to tell Lin he would meet him provided he received a guarantee of safe conduct. Dent further stalled by sending Robert Inglis, one of his partners, to a meeting with Lin's subordinates. Charles Elliot then ordered all British ships in Canton to head for the safety of Hong Kong island before he himself arrived at the foreign factories on 24 March, 1839, three days after the expiry of Lin's deadline. After raising the Union Jack, the British superintendent of trade announced that all foreign merchants were henceforth under the protection of the British government. [17] Chinese soldiers then sealed off access to the factory area and began a campaign to intimidate the foreign residents trapped inside. Elliot read out a petition stating that all opium was to be handed over, promising compensation from the British government for the costs of the merchandise, with a deadline of six pm on 27 March. By nightfall, British traders had agreed to surrender around 20,000 chests of opium (approximately 1,300 long tons (1,321 t)) [5] with a value of 2,000,000 British pounds. [18] Even though Lin believed that the British had surrendered all their supplies, the factories remained in a state of virtual siege as the commissioner demanded that the Americans, the French, the Indians and the Dutch hand over a further 20,000 chests in total. [19] This would have been impossible; the French were absent from Canton at the time, the Indians and Americans claimed that any opium they held belonged to others while the Dutch did not deal in the drug.

Destruction of opium

At an elevated spot on the shore a space was barricaded in; here a pit was dug, and filled with opium mixed with brine: into this, again, lime was thrown, forming a scalding furnace, which made a kind of boiling soup of the opium. In the evening the mixture was let out by sluices, and allowed to flow out to sea with the ebb tide.

Lin's initial plan called for the transport of the seized opium under Chinese guard to Lankit Island (Longxue Island), some 5 miles (8.0 km) south of the Bogue forts and 35 miles (56 km) from Canton. However, he agreed that men assigned by Elliot could instead carry out the task. [21] Deng Tingzhen together with Lin arrived at the Bogue on 11 April. According to a Chinese account of events, at this point Lin offered three catties [A] of tea for every one of opium surrendered. [22] The Jardine Matheson clippers Austin and Hercules moored in the river and began the transfer of opium in their holds but rough waters forced them to relocate to Chuanbi Island further down river and close to the Shajiao Fort (沙角炮台) outside Humen Town. By 21 May 1839, 20,283 chests had been unloaded at Chuanbi. Pleased with the outcome, Daogguang sent Lin a roebuck venison to symbolise an imminent promotion and a hand-written scroll inscribed with the Chinese characters for good luck and long life. [23] On 24 May, all foreign merchants previously involved in the opium trade received orders from Lin to leave China forever. They departed in a flotilla under the command of Charles Elliot, who by now had become persona non grata with the British government for his acquiescence to Chinese demands.

Lin then set about destroying the seized opium. After encircling the site with a bamboo fence to prevent theft, three stone pits, lined with wood, were dug into which was poured the seized opium along with lime and salt. A minor interruption occurred when one man was caught trying to remove a quantity of the drug—he was beheaded on the spot. [24] Once the pits had been filled with sea water, labourers mixed salt into the irrigated opium burning pond before pouring in the stolen opium and quicklime. When lime reacts with water, it produces high temperatures that dissolve certain opium. The pond water is released into the sea as the tide recedes. On the 23rd, 19,187 boxes and 2,119 bags of opium, totaling 2,376,254 kilogram, were burned. [25] When the task was finished, the American missionary, Elijah Coleman Bridgman, who witnessed events, commented: "The degree of care and fidelity, with which the whole work was conducted, far exceeded our expectations ..." [26]

Aftermath

Once the opium had been destroyed, Elliot promised the merchants compensation for their losses from the British government. However, the country's parliament had never agreed to such an offer, and instead thought that it was the Chinese government's responsibility to pay reparations to the merchants. Frustrated that any repayment for the destroyed opium seemed unlikely, the merchants turned to William Jardine, who had left Canton just prior to Lin's arrival. Jardine believed that open warfare was the only way to force compensation from the Qing authorities and in London he began a campaign to sway the British government, [27] meeting with Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston in October 1839. The following March, in the face of strong opposition from, among others, the Chartists, the pro-war lobby eventually won 271 to 262 in a House of Commons debate on whether to despatch a naval force to China. [28] In the spring of 1840 an expeditionary force of sixteen warships and 31 other ships left India for China, [27] which would become involved in multiple Sino-British battles in the First Opium War that followed.

Legacy

International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking is a United Nations International Day against drug abuse and the illegal drug trade. The honour of having started the campaign against narcotic drugs belongs - in the pre-League time - to the American Bishop Charles H. Brent of the Philippines who, in 1906, drew the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt to the deplorable opium situation in the Far East. [29] It is observed annually on 26 Jun that Chinese government and media commemorate Lin Zexu's effort of dismantling the harmful opium trade in Humen, Guangdong, ending on 25 June 1839.[ citation needed ]

A statue of Lin Zexu stands in Chatham Square in Chinatown, New York City, United States. The base of the statue is inscribed with "Pioneer in the war against drugs" in English and Chinese. [30]

The "Lin Zexu Memorial" to commemorate destruction of the opium opened outside Humen in 1957 and in 1972 was renamed "Anti-British Memorial for Humen People of the Opium War." It later became the "Opium War Museum" with additional responsibility for administration of the ruins of the Shajiao and Weiyuan Batteries. A further "Sea Battle Museum" on the site opened to the public in December 1999. [31]

Notes

Related Research Articles

William Jardine was a Scottish opium trader and physician who co-founded the Hong Kong–based conglomerate Jardine, Matheson & Co. Educated in medicine at the University of Edinburgh, in 1802 Jardine obtained a diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. The next year, he became a surgeon's mate aboard the Brunswick belonging to the East India Company, and set sail for India. In May 1817, he abandoned medicine for trade.

The Treaty of Nanking was the peace treaty which ended the First Opium War (1839–1842) between Great Britain and the Qing dynasty of China on 29 August 1842. It was the first of what the Chinese later termed the "unequal treaties".

The First Opium War, also known as the Anglo-Chinese War, was a series of military engagements fought between the British Empire and the Qing dynasty of China between 1839 and 1842. The immediate issue was the Chinese enforcement of their ban on the opium trade by seizing private opium stocks from mainly British merchants at Guangzhou and threatening to impose the death penalty for future offenders. Despite the opium ban, the British government supported the merchants' demand for compensation for seized goods, and insisted on the principles of free trade and equal diplomatic recognition with China. Opium was Britain's single most profitable commodity trade of the 19th century. After months of tensions between the two states, the Royal Navy launched an expedition in June 1840, which ultimately defeated the Chinese using technologically superior ships and weapons by August 1842. The British then imposed the Treaty of Nanking, which forced China to increase foreign trade, give compensation, and cede Hong Kong Island to the British. Consequently, the opium trade continued in China. Twentieth-century nationalists considered 1839 the start of a century of humiliation, and many historians consider it the beginning of modern Chinese history.

The Opium Wars were two conflicts waged between China and Western powers during the mid-19th century.

Lin Zexu, courtesy name Yuanfu, was a Chinese political philosopher and politician. He was a head of state (Viceroy), Governor General, scholar-official, and under the Daoguang Emperor of the Qing dynasty best known for his role in the First Opium War of 1839–42. He was from Fuzhou, Fujian Province. Lin's forceful opposition to the opium trade was a primary catalyst for the First Opium War. He is praised for his constant position on the "moral high ground" in his fight, but he is also blamed for a rigid approach which failed to account for the domestic and international complexities of the problem. The Emperor endorsed the hardline policies and anti-drugs movement advocated by Lin, but placed all responsibility for the resulting disastrous Opium War onto Lin.

The Thirteen Factories, also known as the Canton Factories, was a neighbourhood along the Pearl River in southwestern Guangzhou (Canton) in the Qing Empire from c. 1684 to 1856 around modern day Xiguan, in Guangzhou's Liwan District. These warehouses and stores were the principal and sole legal site of most Western trade with China from 1757 to 1842. The factories were destroyed by fire in 1822 by accident, in 1841 amid the First Opium War, and in 1856 at the onset of the Second Opium War. The factories' importance diminished after the opening of the treaty ports and the end of the Canton System under the terms of the 1842 Anglo-Chinese Treaty of Nanking. After the Second Opium War, the factories were not rebuilt at their former site south of Guangzhou's old walled city but moved, first to Henan Island across the Pearl River and then to Shamian Island south of Guangzhou's western suburbs. Their former site is now part of Guangzhou Cultural Park.

Wu Bingjian, trading as "Houqua" and better known in the West as "Howqua" or "Howqua II", was a hong merchant in the Thirteen Factories, head of the E-wo hong and leader of the Canton Cohong. He was once the richest man in the world.

Qishan, courtesy name Jing'an, was a Mongol nobleman and official of the late Qing dynasty. He was of Khalkha Mongol and Borjigit descent, and his family was under the Plain Yellow Banner of the Manchu Eight Banners. He is best known for negotiating the Convention of Chuanbi on behalf of the Qing government with the British during the First Opium War of 1839–42.

A hong was a type of Chinese merchant establishment and its associated type of building. Hongs arose in Guangzhou as intermediaries between Western and Chinese merchants during the 18–19th century, under the Canton System.

The Opium War (鸦片战争) is a 1997 Chinese historical epic film directed by Xie Jin. The winner of the 1997 Golden Rooster and 1998 Hundred Flowers Awards for Best Picture, the film was screened in several international film festivals, notably Cannes and Montreal. The film tells the story of the First Opium War of 1839–1842, which was fought between the Qing Empire of China and the British Empire, from the perspectives of key figures such as the Chinese viceroy Lin Zexu and the British naval diplomat Charles Elliot.

The First Battle of Chuenpi was a relatively minor naval engagement fought between British and Chinese ships at the entrance of the Humen strait (Bogue), Guangdong province, China, on 3 November 1839 near the beginning of the First Opium War. The battle began when the British frigates HMS Hyacinth and HMS Volage opened fire on Chinese ships they perceived as being hostile.

The Second Battle of Chuenpi was fought between British and Chinese forces in the Pearl River Delta, Guangdong province, China, on 7 January 1841 during the First Opium War. The British launched an amphibious attack at the Humen strait (Bogue), capturing the forts on the islands of Chuenpi and Taikoktow. Subsequent negotiations between British Plenipotentiary Charles Elliot and Chinese Imperial Commissioner Qishan resulted in the Convention of Chuenpi on 20 January. As one of the terms of the agreement, Elliot announced the cession of Hong Kong Island to the British Empire, after which the British took formal possession of the island on 26 January.

The Battle of Kowloon was a skirmish between British and Chinese vessels off the Kowloon Peninsula, China, on 4 September 1839, located in Hong Kong, although Kowloon was then part of the Guangdong province. The skirmish was the first armed conflict of the First Opium War and occurred when British boats opened fire on Chinese war junks enforcing a food sales embargo on the British community. The ban was ordered after a Chinese man died in a brawl with drunk British sailors at Tsim Sha Tsui. The Chinese authorities did not consider the punishment to be sufficient as meted out by British officials, so they suspended food supplies in an attempt to force the British to turn over the culprit.

Guan Tianpei, courtesy name Zhongyin (仲因), art name Zipu (滋圃), was a Chinese admiral of the Qing dynasty who served in the First Opium War. His Chinese title was "Commander-in-Chief of Naval Forces". In 1838, he established courteous relations with British Rear-Admiral Frederick Maitland. Guan fought in the First Battle of Chuenpi (1839), the Second Battle of Chuenpi (1841), and the Battle of the Bogue (1841). The British account described his death in the Anunghoy forts during the Battle of the Bogue on 26 February 1841 as follows:

Among these [Chinese officers], the most distinguished and lamented was poor old Admiral Kwan, whose death excited much sympathy throughout the force; he fell by a bayonet wound in his breast, as he was meeting his enemy at the gate of Anunghoy, yielding up his brave spirit willingly to a soldier's death, when his life could only be preserved with the certainty of degradation. He was altogether a fine specimen of a gallant soldier, unwilling to yield when summoned to surrender because to yield would imply treason.

Yang Fang (1770–1846) was a Han Chinese general and diplomat during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Born in Songtao, Guizhou Province, he joined the military as a young man and became a secretary, where he came to the attention of General Yang Yuchun, who recommended him for military school.

Lu Kun, was a Chinese politician of the Qing dynasty. He was a student of politician and scholar Ruan Yuan. He was born in Zhuozhou Prefecture, Shuntian Fu (顺天府).

The history of opium in China began with the use of opium for medicinal purposes during the 7th century. In the 17th century the practice of mixing opium with tobacco for smoking spread from Southeast Asia, creating a far greater demand.

Hercules was built at Calcutta in 1814. She acquired British registry and traded between Britain and India under a license from the British East India Company (EIC), before returning to Calcutta registry. She then traded opium between India and China, and became an opium receiving ship for Jardine Matheson. In 1839 she was one of the vessels that surrendered her store of opium to be burned at the behest of Chinese officials at Canton. This incident was one of the proximate causes of the First Opium War (1839–1842). Her owners apparently sold her to American owners in 1839.

Events from the year 1841 in China.

Events from the year 1839 in China.

References

Citations

- ↑ Wright 2000, p. 21.

- ↑ Zhang 2006, p. 23.

- ↑ Ebrey 2010, p. 236.

- 1 2 Alexander 1856, p. 11.

- 1 2 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Policy Analysis and Research Branch 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ Newbould 1990, p. 111.

- ↑ Canton Free Press, 14 February 1837; reprinted in The Times (London), 31 March 1837

- ↑ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 34.

- ↑ THE OPIUM WARS IN CHINA

- ↑ Teng & Fairbank 1979, p. 23.

- ↑ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 41.

- 1 2 Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 43.

- ↑ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 45.

- ↑ Ouchterlony 1844, p. 13.

- ↑ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 46.

- ↑ Boswell, James (1785). "Affairs of the East Indies". The Scots Magazine. 47. Edinburgh: Sands, Brymer, Murray and Cochran: 355.

- ↑ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 47.

- ↑ Melancon, Glenn (1999), "Honor in Opium? The British Declaration of War on China, 1839-1840", International History Review, 21 (4): 859, doi:10.1080/07075332.1999.9640880

- ↑ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 52.

- ↑ Parker & Wei 1888, p. 6-7.

- ↑ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 53.

- ↑ Parker & Wei 1888, p. 6.

- ↑ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 54.

- ↑ Tamura 1997, p. 98.

- ↑ "China Commemorates Anti-opium Hero". 4 June 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Elijah Coleman Bridgman". The Chinese Repository. VIII: 74. 1840.

- 1 2 Ebrey 2010, p. 239.

- ↑ Beeching 1975, p. 111.

- ↑ Bertil A. RENBORG, , Office on Drugs and Crime, United Nations, 1 Jan 1964.

- ↑ David Chen, Chinatown's Fujianese Get a Statue, New York Times, 20 November 1997.

- ↑ "The Opium War Museum" . Retrieved 24 March 2014.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Robert (1856). The Rise and Progress of British Opium Smuggling: The Illegality of the East India Company's Monopoly of the Drug, and Its Injurious Effects Upon India, China, and the Commerce of Great Britain. Five Letters Addressed to the Earl of Shaftesbury. London: Judd and Glass.

- Beeching, Jack (1975). The Chinese Opium Wars. Hutchinson. ISBN 9780091227302.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, ed. (2010). "9. Manchus and Imperialism: The Qing Dynasty 1644–1900". The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12433-1.

- Hanes, W. Travis; Sanello, Frank (2002). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another . Sourcebooks. ISBN 9781402201493.

- Newbould, Ian (1990). Whiggery and Reform, 1830-41: The Politics of Government. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804717595.

- Ouchterlony, John (1844). The Chinese War: An Account of All the Operations of the British Forces from the Commencement to the Treaty of Nanking. London: Saunders and Otley.

- Parker, Edward Harper; Wei, Yuan (1888). 聖武記 [Chinese Account of the Opium War]. The Pagoda Library. Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh.

- Tamura, Eileen H. (1997). Chapter 2; Civilizations in Collision: China in Transition, 1750–1920. China: Understanding Its Past. Vol. 1. Curriculum Research & Development Group, University of Hawaii and University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824819231.

- Teng, Ssu-yu; Fairbank, John King (1979). China's Response to the West: A Documentary Survey, 1839-1923. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674120259.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Policy Analysis and Research Branch (2010). A Century of International Drug Control. Bulletin on Narcotics. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. ISBN 9789211482454.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)

- Wright, David (2000). Translating Science: The Transmission of Western Chemistry Into Late Imperial China, 1840-1900. Sinica Leidensia. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004117761.

- Zhang, Weibin (2006). Hong Kong: The Pearl Made of British Mastery and Chinese Docile-diligence. Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 9781594546006.

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.

| Destruction of opium at Humen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 虎門銷煙 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 虎门销烟 | ||||||

| |||||||