Riverside South is an urban development project in the Lincoln Square neighborhood of the Upper West Side of Manhattan, New York City, United States. Developed by the businessman Donald Trump in collaboration with six civic associations, the largely residential complex is on 57 acres (23 ha) of land along the Hudson River between 59th Street and 72nd Street. The $3 billion project, which replaced a New York Central Railroad yard known as the 60th Street Yard, includes multiple residential towers and a extension of Riverside Park.

Pacific Park is a mixed-use commercial and residential development project by Forest City Ratner in Brooklyn, New York City. It will consist of 17 high-rise buildings near Brooklyn's Prospect Heights, adjacent to Downtown Brooklyn, Park Slope, and Fort Greene neighborhoods. The project overlaps part of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, but also extends toward the adjacent brownstone neighborhoods. Of the 22-acre (8.9 ha) project, 8.4 acres (3.4 ha) is located over a Long Island Rail Road train yard. A major component of the project is the Barclays Center sports arena, which opened on September 21, 2012. Formerly named Atlantic Yards, the project was renamed by the developer in August 2014 as part of a rebranding.

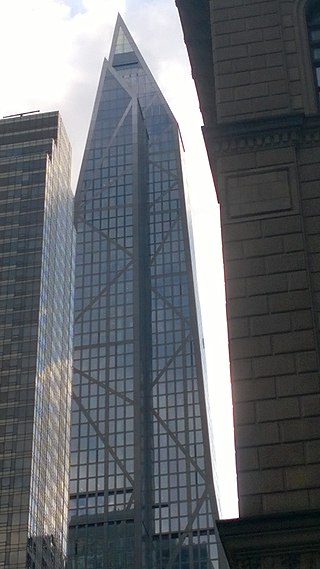

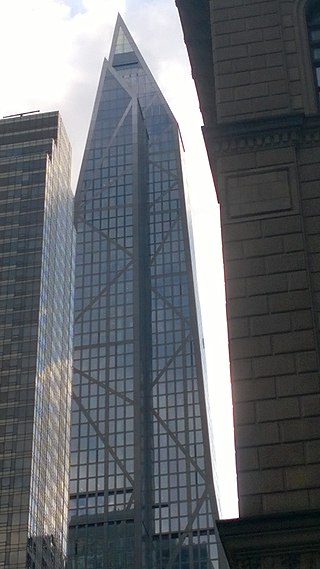

53 West 53 is a supertall skyscraper at 53 West 53rd Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, adjacent to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). It was developed by the real estate companies Pontiac Land Group and Hines. With a height of 1,050 ft (320 m), 53 West 53 is the tenth-tallest completed building in the city as of November 2019.

15 Hudson Yards is a residential skyscraper on Manhattan's West Side, completed in 2019. Located in Chelsea near Hell's Kitchen Penn Station area, the building is a part of the Hudson Yards project, a plan to redevelop the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's West Side Yards.

Essex Crossing is an under-construction mixed-use development in New York City's Lower East Side, at the intersection of Delancey Street and Essex Street just north of Seward Park. Essex Crossing will comprise nearly 2,000,000 sq ft (200,000 m2) of space on 6 acres and will cost an estimated US$1.1 billion. Part of the existing Seward Park Urban Renewal Area (SPURA), the development will sit on a total of nine city blocks, most of them occupied by parking lots that replaced tenements razed in 1967.

One Vanderbilt is a 73-story supertall skyscraper at the corner of 42nd Street and Vanderbilt Avenue in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox for developer SL Green Realty, the skyscraper opened in 2020. Its roof is 1,301 feet (397 m) high and its spire is 1,401 feet (427 m) above ground, making it the city's fourth-tallest building after One World Trade Center, Central Park Tower, and 111 West 57th Street.

Hill West Architects is a New York City based architecture firm which works on the planning and design of high-rise residential and hospitality buildings, retail structures and multi-use complexes. They have participated in the design of prominent structures in the New York City metropolitan area. The firm was founded in 2009 by Alan Goldstein, L. Stephen Hill and David West.

The Brooklyn Tower is a supertall mixed-use, primarily residential skyscraper in the Downtown Brooklyn neighborhood of New York City. Developed by JDS Development Group, it is situated on the north side of DeKalb Avenue near Flatbush Avenue. The main portion of the skyscraper is a 74-story, 1,066-foot (325 m) residential structure designed by SHoP Architects and built from 2018 to 2022. Preserved at the skyscraper's base is the Dime Savings Bank Building, designed by Mowbray and Uffinger, which dates to the 1900s.

The Copper are a pair of luxury residential skyscrapers in the Murray Hill neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. The buildings were developed by JDS Development and were designed by SHoP Architects with interiors by SHoP and K&Co. The buildings are one of several major collaborations between JDS and SHoP; others include 111 West 57th Street, also in Manhattan, and The Brooklyn Tower in Brooklyn.

45 Broad Street is a residential building being constructed in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City. The building was originally planned as Lower Manhattan's tallest residential tower. Excavation started in 2017, but as of 2020, construction is on hold.

Yuh-Line Niou is an American politician who served as a member of the New York State Assembly for the 65th district. The Lower Manhattan district, which is heavily Democratic and over 40% Asian American, includes Chinatown, the Financial District, Battery Park City, and the Lower East Side. Niou is the first Asian American elected to the State Assembly for the district. She was a candidate for Congress in New York's newly redrawn 10th congressional district in 2022.

Waterline Square is a 5-acre (2.0 ha), $2.3 billion luxury condominium and rental development near the Hudson River on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. The complex includes three residential towers with 1,132 units and 3 acres (1.2 ha) of park, along with 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2) of amenity space. The residences range in size from one to five bedrooms.

The Alloy Block is an under-construction mixed-use development in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, New York City, near Downtown Brooklyn. The first building at 505 State Street is 482 feet (147 m) high and contains 441 residential units and a retail base. A second building at 80 Flatbush Avenue will contain two schools, and the complex will include three additional buildings, including preexisting structures. The structures are being developed by Alloy Development.

19 Dutch is a residential building in the Financial District neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. The building was developed by Carmel Partners and was designed by GK+V, with SLCE Architects as the architect of record. GK+V also designed the nearby 5 Beekman. The building contains 482 units and retail space on the first several floors. In February 2018, Carmel began leasing out the 97 affordable apartments. Carmel placed the building for sale in 2022, and Amancio Ortega, the founder of Zara, agreed in July 2022 to buy 19 Dutch via his holding firm Pontegadea for about $500 million.

The Bedford Union Armory is a historic National Guard armory building located in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York City. It is a brick and stone castle-like structure built in 1903 and opened in 1908 and was used by the U.S. Army for training, equipment storage and even as a horse stable. The current community center opened in October 2021.

Little Island at Pier 55 is an artificial island and a public park within Hudson River Park, just off the western coast of Manhattan in New York City. Designed by Heatherwick Studio, it is near the intersection of West Street and West 13th Street in the Meatpacking District and Chelsea neighborhoods of Manhattan. It is located atop Hudson River's Pier 55, connected to the rest of Hudson River Park by footbridges at 13th and 14th Streets. Little Island has two concession stands, a small stage, and a 687-seat amphitheater.

St. John's Terminal, also known as 550 Washington Street, is a building on Washington Street in the Hudson Square neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. Designed by Edward A. Doughtery, it was built in 1934 by the New York Central Railroad as a terminus of the High Line, an elevated freight line along Manhattan's West Side used for transporting manufacturing-related goods. The terminal could accommodate 227 train cars. The three floors, measuring 205,000 square feet (19,000 m2) each, were the largest in New York City at the time of their construction.

Sutton 58 is a residential skyscraper in the Sutton Place neighborhood of Midtown East, Manhattan in New York City.

Carmel Place is a nine-story apartment building at 335 East 27th Street in the Kips Bay neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. Completed in 2016, it was New York City's first microapartment building. The project won a competition sponsored by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development to design, construct and operate a "micro-unit" apartment building on a city-owned site and pilot the use of compact apartments to accommodate smaller households.

DXA Studio is an American architecture firm based in New York City and known for its work on the conversion of the William Ulmer Brewery in Brooklyn and the design of The Rowan Astoria, a residential development in Queens that set a record in 2021 for the most expensive condominium unit sold in the borough.