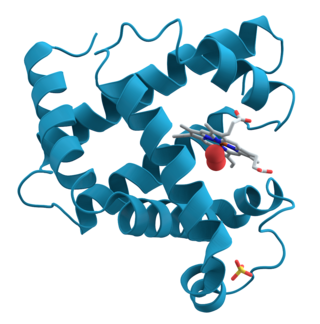

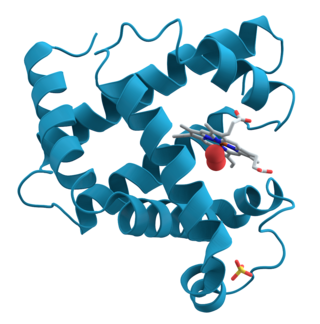

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn are wrapped into 30-nanometer fibers that form tightly packed chromatin. Histones prevent DNA from becoming tangled and protect it from DNA damage. In addition, histones play important roles in gene regulation and DNA replication. Without histones, unwound DNA in chromosomes would be very long. For example, each human cell has about 1.8 meters of DNA if completely stretched out; however, when wound about histones, this length is reduced to about 9 micrometers (0.09 mm) of 30 nm diameter chromatin fibers.

In genetics, a promoter is a sequence of DNA to which proteins bind to initiate transcription of a single RNA transcript from the DNA downstream of the promoter. The RNA transcript may encode a protein (mRNA), or can have a function in and of itself, such as tRNA or rRNA. Promoters are located near the transcription start sites of genes, upstream on the DNA . Promoters can be about 100–1000 base pairs long, the sequence of which is highly dependent on the gene and product of transcription, type or class of RNA polymerase recruited to the site, and species of organism.

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype. These products are often proteins, but in non-protein-coding genes such as transfer RNA (tRNA) and small nuclear RNA (snRNA), the product is a functional non-coding RNA. The process of gene expression is used by all known life—eukaryotes, prokaryotes, and utilized by viruses—to generate the macromolecular machinery for life.

Transcription is the process of copying a segment of DNA into RNA. Some segments of DNA are transcribed into RNA molecules that can encode proteins, called messenger RNA (mRNA). Other segments of DNA are transcribed into RNA molecules called non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs).

In genetics, an enhancer is a short region of DNA that can be bound by proteins (activators) to increase the likelihood that transcription of a particular gene will occur. These proteins are usually referred to as transcription factors. Enhancers are cis-acting. They can be located up to 1 Mbp away from the gene, upstream or downstream from the start site. There are hundreds of thousands of enhancers in the human genome. They are found in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Active enhancers typically get transcribed as enhancer or regulatory non-coding RNA, whose expression levels correlate with mRNA levels of target genes.

A regulatory sequence is a segment of a nucleic acid molecule which is capable of increasing or decreasing the expression of specific genes within an organism. Regulation of gene expression is an essential feature of all living organisms and viruses.

In molecular biology and genetics, transcriptional regulation is the means by which a cell regulates the conversion of DNA to RNA (transcription), thereby orchestrating gene activity. A single gene can be regulated in a range of ways, from altering the number of copies of RNA that are transcribed, to the temporal control of when the gene is transcribed. This control allows the cell or organism to respond to a variety of intra- and extracellular signals and thus mount a response. Some examples of this include producing the mRNA that encode enzymes to adapt to a change in a food source, producing the gene products involved in cell cycle specific activities, and producing the gene products responsible for cellular differentiation in multicellular eukaryotes, as studied in evolutionary developmental biology.

In biology, the epigenome of an organism is the collection of chemical changes to its DNA and histone proteins that affects when, where, and how the DNA is expressed; these changes can be passed down to an organism's offspring via transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Changes to the epigenome can result in changes to the structure of chromatin and changes to the function of the genome. The human epigenome, including DNA methylation and histone modification, is maintained through cell division. The epigenome is essential for normal development and cellular differentiation, enabling cells with the same genetic code to perform different functions. The human epigenome is dynamic and can be influenced by environmental factors such as diet, stress, and toxins.

RNA polymerase II is a multiprotein complex that transcribes DNA into precursors of messenger RNA (mRNA) and most small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and microRNA. It is one of the three RNAP enzymes found in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. A 550 kDa complex of 12 subunits, RNAP II is the most studied type of RNA polymerase. A wide range of transcription factors are required for it to bind to upstream gene promoters and begin transcription.

Eukaryotic transcription is the elaborate process that eukaryotic cells use to copy genetic information stored in DNA into units of transportable complementary RNA replica. Gene transcription occurs in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. Unlike prokaryotic RNA polymerase that initiates the transcription of all different types of RNA, RNA polymerase in eukaryotes comes in three variations, each translating a different type of gene. A eukaryotic cell has a nucleus that separates the processes of transcription and translation. Eukaryotic transcription occurs within the nucleus where DNA is packaged into nucleosomes and higher order chromatin structures. The complexity of the eukaryotic genome necessitates a great variety and complexity of gene expression control.

ChIP-sequencing, also known as ChIP-seq, is a method used to analyze protein interactions with DNA. ChIP-seq combines chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with massively parallel DNA sequencing to identify the binding sites of DNA-associated proteins. It can be used to map global binding sites precisely for any protein of interest. Previously, ChIP-on-chip was the most common technique utilized to study these protein–DNA relations.

Long non-coding RNAs are a type of RNA, generally defined as transcripts more than 200 nucleotides that are not translated into protein. This arbitrary limit distinguishes long ncRNAs from small non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), and other short RNAs. Given that some lncRNAs have been reported to have the potential to encode small proteins or micro-peptides, the latest definition of lncRNA is a class of transcripts of over 200 nucleotides that have no or limited coding capacity. However, John S. Mattick and colleagues suggested to change definition of long non-coding RNAs to transcripts more than 500 nt, which are mostly generated by Pol II. That means that question of lncRNA exact definition is still under discussion in the field. Long intervening/intergenic noncoding RNAs (lincRNAs) are sequences of transcripts that do not overlap protein-coding genes.

RNA polymerase II holoenzyme is a form of eukaryotic RNA polymerase II that is recruited to the promoters of protein-coding genes in living cells. It consists of RNA polymerase II, a subset of general transcription factors, and regulatory proteins known as SRB proteins.

Epigenomics is the study of the complete set of epigenetic modifications on the genetic material of a cell, known as the epigenome. The field is analogous to genomics and proteomics, which are the study of the genome and proteome of a cell. Epigenetic modifications are reversible modifications on a cell's DNA or histones that affect gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. Epigenomic maintenance is a continuous process and plays an important role in stability of eukaryotic genomes by taking part in crucial biological mechanisms like DNA repair. Plant flavones are said to be inhibiting epigenomic marks that cause cancers. Two of the most characterized epigenetic modifications are DNA methylation and histone modification. Epigenetic modifications play an important role in gene expression and regulation, and are involved in numerous cellular processes such as in differentiation/development and tumorigenesis. The study of epigenetics on a global level has been made possible only recently through the adaptation of genomic high-throughput assays.

RNA polymerase IV is an enzyme that synthesizes small interfering RNA (siRNA) in plants, which silence gene expression. RNAP IV belongs to a family of enzymes that catalyze the process of transcription known as RNA Polymerases, which synthesize RNA from DNA templates. Discovered via phylogenetic studies of land plants, genes of RNAP IV are thought to have resulted from multistep evolution processes that occurred in RNA Polymerase II phylogenies. Such an evolutionary pathway is supported by the fact that RNAP IV is composed of 12 protein subunits that are either similar or identical to RNA polymerase II, and is specific to plant genomes. Via its synthesis of siRNA, RNAP IV is involved in regulation of heterochromatin formation in a process known as RNA directed DNA Methylation (RdDM).

H3K4me3 is an epigenetic modification to the DNA packaging protein Histone H3 that indicates tri-methylation at the 4th lysine residue of the histone H3 protein and is often involved in the regulation of gene expression. The name denotes the addition of three methyl groups (trimethylation) to the lysine 4 on the histone H3 protein.

H3K27me3 is an epigenetic modification to the DNA packaging protein histone H3. It is a mark that indicates the tri-methylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 protein.

H3R17me2 is an epigenetic modification to the DNA packaging protein histone H3. It is a mark that indicates the di-methylation at the 17th arginine residue of the histone H3 protein. In epigenetics, arginine methylation of histones H3 and H4 is associated with a more accessible chromatin structure and thus higher levels of transcription. The existence of arginine demethylases that could reverse arginine methylation is controversial.

H3S10P is an epigenetic modification to the DNA packaging protein histone H3. It is a mark that indicates the phosphorylation the 10th serine residue of the histone H3 protein.

H3S28P is an epigenetic modification to the DNA packaging protein histone H3. It is a mark that indicates the phosphorylation the 28th serine residue of the histone H3 protein.