Stalinism is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1924 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalin had previously made a career as a gangster and robber, working to fund revolutionary activities, before eventually becoming General Secretary of the Soviet Union. Stalinism included the creation of a one man totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory of socialism in one country, forced collectivization of agriculture, intensification of class conflict, a cult of personality, and subordination of the interests of foreign communist parties to those of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which Stalinism deemed the leading vanguard party of communist revolution at the time. After Stalin's death and the Khrushchev Thaw, a period of de-Stalinization began in the 1950s and 1960s, which caused the influence of Stalin's ideology to begin to wane in the USSR.

Consumer goods in the Soviet Union were usually produced by a two-category industry. Group A was "heavy industry", which included all goods that serve as an input required for the production of some other, final good. Group B was "consumer goods", final goods used for consumption, which included food, clothing and shoes, housing, and such heavy-industry products as appliances and fuels that are used by individual consumers. From the early days of the Stalin era, Group A received top priority in economic planning and allocation so as to industrialize the Soviet Union from its previous agricultural economy.

Soviet and communist studies, or simply Soviet studies, is the field of regional and historical studies on the Soviet Union and other communist states, as well as the history of communism and of the communist parties that existed or still exist in some form in many countries, both inside and outside the former Eastern Bloc, such as the Communist Party USA. Aspects of its historiography have attracted debates between historians on several topics, including totalitarianism and Cold War espionage.

The first five-year plan of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was a list of economic goals, implemented by Communist Party General Secretary Joseph Stalin, based on his policy of socialism in one country. Leon Trotsky had delivered a joint report to the April Plenum of the Central Committee in 1926 which proposed a program for national industrialisation and the replacement of annual plans with five-year plans. His proposals were rejected by the Central Committee majority which was controlled by the troika and derided by Stalin at the time. Stalin's version of the five-year plan was implemented in 1928 and took effect until 1932.

The Shakhty Trial was the first important Soviet show trial since the case of the Socialist Revolutionary Party in 1922. Fifty-three engineers and managers from the North Caucasus town of Shakhty were arrested in 1928 after being accused of conspiring to sabotage the Soviet economy with the former owners of the coal mines. The trial was conducted on May 18, 1928, in House of Trade Unions, Moscow. Thirty-four of the accused received prison terms, while eleven were sentenced to death. The remainder were acquitted or received suspended sentences.

John Archibald Getty III is an American historian and professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), who specializes in the history of Russia and the history of the Soviet Union.

In Russian, blat is a form of corruption comprising a system of informal agreements, exchanges of services, connections, Party contacts, or black market deals to achieve results or get ahead.

Sheila Mary Fitzpatrick is an Australian historian, whose main subjects are history of the Soviet Union and history of modern Russia, especially the Stalin era and the Great Purges, of which she proposes a "history from below", and is part of the "revisionist school" of Communist historiography. She has also critically reviewed the concept of totalitarianism and highlighted the differences between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in debates about comparison of Nazism and Stalinism.

Elections to the Supreme Soviet were held in the Soviet Union on 12 December 1937. It was the first election held under the 1936 Soviet Constitution, which had formed the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union to replace the old legislature, the Congress of Soviets of the Soviet Union.

I Chose Freedom: The Personal Political Life of a Soviet Official is a book by the Soviet Ukrainian defector Viktor Kravchenko. It was a bestseller in the United States and Europe. The book was written in 1946 and published in 1947. A review was published in The New York Times that year. I Chose Freedom depicts many episodes in Soviet history, including the Soviet famine of 1932–1933, the Gulag system, and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact (1939).

This is a select bibliography of post-World War II English-language books and journal articles about Stalinism and the Stalinist era of Soviet history. Book entries have references to journal reviews about them when helpful and available. Additional bibliographies can be found in many of the book-length works listed below.

This is a select bibliography of English language books and journal articles about the post-Stalinist era of Soviet history. A brief selection of English translations of primary sources is included. The sections "General surveys" and "Biographies" contain books; other sections contain both books and journal articles. Book entries have references to journal articles and reviews about them when helpful. Additional bibliographies can be found in many of the book-length works listed below; see Further reading for several book and chapter-length bibliographies. The External links section contains entries for publicly available select bibliographies from universities.

Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928 is the first volume in the three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin by American historian and Princeton Professor of History Stephen Kotkin. It was originally published in November 2014 by Penguin Random House and as an audiobook in December 2014 by Recorded Books. The second volume, Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941, was published in 2017 by Penguin Random House.

Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941 is the second volume in the three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin by American historian and Princeton Professor of History Stephen Kotkin. Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941 was originally published in October 2017 by Penguin Random House and then as an audiobook in December 2017 by Recorded Books. The first volume, Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928, was published in 2014 by Penguin Random House and the third and final volume, Miscalculation and the Mao Eclipse, is scheduled to be published after 2024.

Stalin's Peasants or Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village after Collectivization is a book by the Soviet scholar and historian Sheila Fitzpatrick first published in 1994 by Oxford University Press. It was released in 1996 in a paperback edition and reissued in 2006 by Oxford University Press. Sheila Fitzpatrick is the Bernadotte E. Schmitt Distinguished Service Professor (Emeritus), Department of History, University of Chicago.

Below is a list of post World War II scholarly books and journal articles written in or translated into English about communism. Items on this list should be considered a non-exhaustive list of reliable sources related to the theory and practice of communism in its different forms.

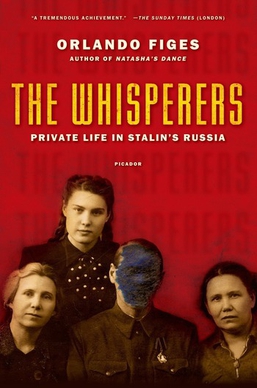

The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia is a history of private life in the Soviet Union during Stalinism, written by Orlando Figes. It was published in 2007 by Metropolitan Books and as an audiobook in 2018 by Audible Studios.

This is a select bibliography of English language books and journal articles about the Soviet Union during the Second World War, the period leading up to the war, and the immediate aftermath. For works on Stalinism and the history of the Soviet Union during the Stalin era, please see Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union. Book entries may have references to reviews published in English language academic journals or major newspapers when these could be considered helpful.

This is a select bibliography of English-language books and journal articles about the history of Ukraine. Book entries have references to journal reviews about them when helpful and available. Additional bibliographies can be found in many of the book-length works listed below. See the bibliography section for several additional book and chapter-length bibliographies from academic publishers and online bibliographies from historical associations and academic institutions.

David Joravsky was an American professor of history, specializing in the Soviet Union's academics in the biological sciences and related politics.