Related Research Articles

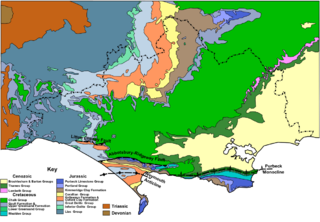

Dorset is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. Covering an area of 2,653 square kilometres (1,024 sq mi); it borders Devon to the west, Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north-east, and Hampshire to the east. The great variation in its landscape owes much to the underlying geology, which includes an almost unbroken sequence of rocks from 200 to 40 million years ago (Mya) and superficial deposits from 2 Mya to the present. In general, the oldest rocks appear in the far west of the county, with the most recent (Eocene) in the far east. Jurassic rocks also underlie the Blackmore Vale and comprise much of the coastal cliff in the west and south of the county; although younger Cretaceous rocks crown some of the highpoints in the west, they are mainly to be found in the centre and east of the county.

The geology of Hampshire in southern England broadly comprises a gently folded succession of sedimentary rocks dating from the Cretaceous and Palaeogene periods. The lower (early) Cretaceous rocks are sandstones and mudstones whilst those of the upper (late) Cretaceous are the various formations which comprise the Chalk Group and give rise to the county's downlands. Overlying these rocks are the less consolidated Palaeogene clays, sands, gravels and silts of the Lambeth, Thames and Bracklesham Groups which characterise the Hampshire Basin.

Poole Bay is a bay in the English Channel, on the coast of Dorset in southern England, which stretches 16 km from Sandbanks at the mouth of Poole Harbour in the west, to Hengistbury Head in the east. Poole Bay is a relatively shallow embayment and consists of steep sandstone cliffs and several 'chines' that allow easy access to the sandy beaches below. The coast along the bay is continuously built up, and is part of the South East Dorset conurbation, including parts of the towns of Poole, Bournemouth and Christchurch. The bay is also called Bournemouth Bay, because much of it is occupied by Bournemouth.

The Lambeth Group is a stratigraphic group, a set of geological rock strata in the London and Hampshire Basins of southern England. It comprises a complex of vertically and laterally varying gravels, sands, silts and clays deposited between 56-55 million years before present during the Ypresian age. It is found throughout the London Basin with a thickness between 10m and 30m and the Hampshire Basin with a thickness between 50m and less than 25m. Although this sequence only crops out in these basins, the fact that it underlies 25% of London at a depth of less than 30m means the formation is of engineering interest for tunnelling and foundations.

The Fylde is a coastal plain in western Lancashire, England. It is roughly a 13-mile-long (21-kilometre) square-shaped peninsula, bounded by Morecambe Bay to the north, the Ribble estuary to the south, the Irish Sea to the west, and the foot of the Bowland hills to the east which approximates to a section of the M6 motorway and West Coast Main Line.

The geology of London comprises various differing layers of sedimentary rock upon which London, England is built.

The Geology of Kansas encompasses the geologic history of the US state of Kansas and the present-day rock and soil that is exposed there. Rock that crops out in Kansas was formed during the Phanerozoic eon, which consists of three geologic eras: the Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic. Paleozoic rocks at the surface in Kansas are primarily from the Mississippian, Pennsylvanian and Permian periods.

The Hampshire Basin is a geological basin of Palaeogene age in southern England, underlying parts of Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, Dorset, and Sussex. Like the London Basin to the northeast, it is filled with sands and clays of Paleocene and younger ages and it is surrounded by a broken rim of chalk hills of Cretaceous age.

The geology of East Sussex is defined by the Weald–Artois anticline, a 60 kilometres (37 mi) wide and 100 kilometres (62 mi) long fold within which caused the arching up of the chalk into a broad dome within the middle Miocene, which has subsequently been eroded to reveal a lower Cretaceous to Upper Jurassic stratigraphy. East Sussex is best known geologically for the identification of the first dinosaur by Gideon Mantell, near Cuckfield, to the famous hoax of the Piltdown man near Uckfield.

The geology of the Isle of Wight is dominated by sedimentary rocks of Cretaceous and Paleogene age. This sequence was affected by the late stages of the Alpine Orogeny, forming the Isle of Wight monocline, the cause of the steeply-dipping outcrops of the Chalk Group and overlying Paleogene strata seen at The Needles, Alum Bay and Whitecliff Bay.

The geology of Suffolk in eastern England largely consists of a rolling chalk plain overlain in the east by Neogene clays, sands and gravels and isolated areas of Palaeocene sands. A variety of superficial deposits originating in the last couple of million years overlie this 'solid geology'.

The geology of Essex in southeast England largely consists of Cenozoic marine sediments from the Palaeogene and Neogene periods overlain by a suite of superficial deposits of Quaternary age.

The geology of Kent in southeast England largely consists of a succession of northward dipping late Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks overlain by a suite of unconsolidated deposits of more recent origin.

The geology of Norfolk in eastern England largely consists of late Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks of marine origin covered by an extensive spread of unconsolidated recent deposits.

The geology of West Sussex in southeast England comprises a succession of sedimentary rocks of Cretaceous age overlain in the south by sediments of Palaeogene age. The sequence of strata from both periods consists of a variety of sandstones, mudstones, siltstones and limestones. These sediments were deposited within the Hampshire and Weald basins. Erosion subsequent to large scale but gentle folding associated with the Alpine Orogeny has resulted in the present outcrop pattern across the county, dominated by the north facing chalk scarp of the South Downs. The bedrock is overlain by a suite of Quaternary deposits of varied origin. Parts of both the bedrock and these superficial deposits have been worked for a variety of minerals for use in construction, industry and agriculture.

This article describes the geology of the Broads, an area of East Anglia in eastern England characterised by rivers, marshes and shallow lakes (‘broads’). The Broads is designated as a protected landscape with ‘status equivalent to a national park’.

The geology of Kentucky formed beginning more than one billion years ago, in the Proterozoic eon of the Precambrian. The oldest igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rock is part of the Grenville Province, a small continent that collided with the early North American continent. The beginning of the Paleozoic is poorly attested and the oldest rocks in Kentucky, outcropping at the surface, are from the Ordovician. Throughout the Paleozoic, shallow seas covered the area, depositing marine sedimentary rocks such as limestone, dolomite and shale, as well as large numbers of fossils. By the Mississippian and the Pennsylvanian, massive coal swamps formed and generated the two large coal fields and the oil and gas which have played an important role in the state's economy. With interludes of terrestrial conditions, shallow marine conditions persisted throughout the Mesozoic and well into the Cenozoic. Unlike neighboring states, Kentucky was not significantly impacted by the Pleistocene glaciations. The state has extensive natural resources, including coal, oil and gas, sand, clay, fluorspar, limestone, dolomite and gravel. Kentucky is unique as the first state to be fully geologically mapped.

The geology of Israel includes igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rocks from the Precambrian overlain by a lengthy sequence of sedimentary rocks extending up to the Pleistocene and overlain with alluvium, sand dunes and playa deposits.

The geology of national parks in Britain strongly influences the landscape character of each of the fifteen such areas which have been designated. There are ten national parks in England, three in Wales and two in Scotland. Ten of these were established in England and Wales in the 1950s under the provisions of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. With one exception, all of these first ten, together with the two Scottish parks were centred on upland or coastal areas formed from Palaeozoic rocks. The exception is the North York Moors National Park which is formed from sedimentary rocks of Jurassic age.

The geology of the Peak District National Park in England is dominated by a thick succession of faulted and folded sedimentary rocks of Carboniferous age. The Peak District is often divided into a southerly White Peak where Carboniferous Limestone outcrops and a northerly Dark Peak where the overlying succession of sandstones and mudstones dominate the landscape. The scarp and dip slope landscape which characterises the Dark Peak also extends along the eastern and western margins of the park. Although older rocks are present at depth, the oldest rocks which are to be found at the surface in the national park are dolomitic limestones of the Woo Dale Limestone Formation seen where Woo Dale enters Wye Dale east of Buxton.

References

- 1 2 3 British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale geological map series (England and Wales) sheet no 315 Southampton. 1987

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale geological map series (England and Wales) sheet no 314 Ringwood. 2004

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale geological map series (England and Wales) sheet no 329 Bournemouth. 1991

- ↑ "BGS on-line map images, sheet 330 Lymington - Result Details".

- ↑ "New Forest Explorer Guide, Irons Well - Result Details".