Related Research Articles

The Yorkshire Dales are a series of valleys, or dales, in the Pennines, an upland range in England. They are mostly located in the ceremonial county of North Yorkshire, but extend into Cumbria and Lancashire; they were historically entirely within Yorkshire. The majority of the dales are within the Yorkshire Dales National Park, created in 1954. The exception is the area around Nidderdale, which forms the separate Nidderdale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

The mountains of Whernside, Ingleborough and Pen-y-ghent are collectively known as the Three Peaks. The peaks, which form part of the Pennine range, encircle the head of the valley of the River Ribble in the Yorkshire Dales National Park in the North of England.

Ingleborough is the second-highest mountain in the Yorkshire Dales, England. It is one of the Yorkshire Three Peaks, and is frequently climbed as part of the Three Peaks walk. A large part of Ingleborough is designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest and National Nature Reserve and is the home of a new joint project, Wild Ingleborough, with aims to improve the landscape for wildlife and people.

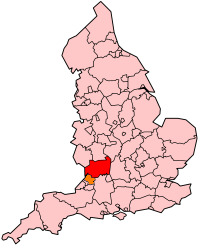

The geology of Shropshire is very diverse with a large number of periods being represented at outcrop. The bedrock consists principally of sedimentary rocks of Palaeozoic and Mesozoic age, surrounding restricted areas of Precambrian metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks. The county hosts in its Quaternary deposits and landforms, a significant record of recent glaciation. The exploitation of the Coal Measures and other Carboniferous age strata in the Ironbridge area made it one of the birthplaces of the Industrial Revolution. There is also a large amount of mineral wealth in the county, including lead and baryte. Quarrying is still active, with limestone for cement manufacture and concrete aggregate, sandstone, greywacke and dolerite for road aggregate, and sand and gravel for aggregate and drainage filters. Groundwater is an equally important economic resource.

Ingleton is a village and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. The village is 17 miles (27 km) from Kendal and 17 miles (27 km) from Lancaster on the western side of the Pennines. It is 9 miles (14 km) from Settle. The River Doe and the River Twiss meet to form the source of the River Greta, a tributary of the River Lune. The village is on the A65 road and at the head of the A687. The B6255 takes the south bank of the River Doe to Ribblehead and Hawes. All that remains of the railway in the village is the landmark Ingleton Viaduct. Arthur Conan Doyle was a regular visitor to the area and was married locally, as his mother lived at Masongill from 1882 to 1917. It has been claimed that there is evidence that the inspiration for the name Sherlock Holmes came from here.

The Yoredale Series, in geology, is a now obsolete term for a local phase of the Carboniferous rocks of the north of England, ranging in age from the Asbian Substage to the Yeadonian Substage. The term Yoredale Group is nowadays applied to the same broad suite of rocks. The name was introduced by J. Phillips on account of the typical development of the phase in Yoredale, Yorkshire.

Carboniferous Limestone is a collective term for the succession of limestones occurring widely throughout Great Britain and Ireland that were deposited during the Dinantian Epoch of the Carboniferous Period. These rocks formed between 363 and 325 million years ago. Within England and Wales, the entire limestone succession, which includes subordinate mudstones and some thin sandstones, is known as the Carboniferous Limestone Supergroup.

Gloucestershire is one of the most geologically and scenically diverse counties in England, with rocks from the Precambrian through to the Jurassic represented. These varying rock-types are responsible for the three major areas of the county, each with its own distinctive scenery and land-use - the Forest of Dean in the west, bordering Wales, the Cotswolds in the east, and in between, the Severn Vale.

The Geology of Yorkshire in northern England shows a very close relationship between the major topographical areas and the geological period in which their rocks were formed. The rocks of the Pennine chain of hills in the west are of Carboniferous origin whilst those of the central vale are Permo-Triassic. The North York Moors in the north-east of the county are Jurassic in age while the Yorkshire Wolds to the south east are Cretaceous chalk uplands. The plain of Holderness and the Humberhead levels both owe their present form to the Quaternary ice ages. The strata become gradually younger from west to east.

The Craven Fault System is the name applied by geologists to the group of crustal faults in the Pennines that form the southern edge of the Askrigg Block and which partly bounds the Craven Basin. Sections of the system's component faults which include the North, Middle and South Craven faults and the Feizor Fault are evident at the surface in the form of degraded faults scarps where Carboniferous Limestone abuts millstone grit. The fault system is approximately coincident with the southwestern edge of the Yorkshire Dales National Park and the northeastern edge of the Bowland Fells.

The geology of Monmouthshire in southeast Wales largely consists of a thick series of sedimentary rocks of different types originating in the Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous, Triassic and Jurassic periods.

The geology of Lancashire in northwest England consists in the main of Carboniferous age rocks but with Triassic sandstones and mudstones at or near the surface of the lowlands bordering the Irish Sea though these are largely obscured by Quaternary deposits.

The geology of County Durham in northeast England consists of a basement of Lower Palaeozoic rocks overlain by a varying thickness of Carboniferous and Permo-Triassic sedimentary rocks which dip generally eastwards towards the North Sea. These have been intruded by a pluton, sills and dykes at various times from the Devonian Period to the Palaeogene. The whole is overlain by a suite of unconsolidated deposits of Quaternary age arising from glaciation and from other processes operating during the post-glacial period to the present. The geological interest of the west of the county was recognised by the designation in 2003 of the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty as a European Geopark.

The Leitrim Group is a lithostratigraphical term coined to refer to the succession of rock strata which occur in Northern Ireland within the Visean and Namurian stages of the Carboniferous Period. The group disconformably overlies the Dartry Limestone of the Tyrone Group.

The geology of national parks in Britain strongly influences the landscape character of each of the fifteen such areas which have been designated. There are ten national parks in England, three in Wales and two in Scotland. Ten of these were established in England and Wales in the 1950s under the provisions of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. With one exception, all of these first ten, together with the two Scottish parks were centred on upland or coastal areas formed from Palaeozoic rocks. The exception is the North York Moors National Park which is formed from sedimentary rocks of Jurassic age.

The geology of Northumberland National Park in northeast England includes a mix of sedimentary, intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks from the Palaeozoic and Cenozoic eras. Devonian age volcanic rocks and a granite pluton form the Cheviot massif. The geology of the rest of the national park is characterised largely by a thick sequence of sedimentary rocks of Carboniferous age. These are intruded by Permian dykes and sills, of which the Whin Sill makes a significant impact in the south of the park. Further dykes were intruded during the Palaeogene period. The whole is overlain by unconsolidated sediments from the last ice age and the post-glacial period.

The Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark is a geopark in the Black Country, a part of the West Midlands region of England. Having previously been an ‘aspiring Geopark’, it was awarded UNESCO Global Geopark status on 10 July 2020.

The geology of the Peak District National Park in England is dominated by a thick succession of faulted and folded sedimentary rocks of Carboniferous age. The Peak District is often divided into a southerly White Peak where Carboniferous Limestone outcrops and a northerly Dark Peak where the overlying succession of sandstones and mudstones dominate the landscape. The scarp and dip slope landscape which characterises the Dark Peak also extends along the eastern and western margins of the park. Although older rocks are present at depth, the oldest rocks which are to be found at the surface in the national park are dolomitic limestones of the Woo Dale Limestone Formation seen where Woo Dale enters Wye Dale east of Buxton.

The geology of Pembrokeshire in Wales inevitably includes the geology of the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park which extends around the larger part of the county's coastline and where the majority of rock outcrops are to be seen. Pembrokeshire's bedrock geology is largely formed from a sequence of sedimentary and igneous rocks originating during the late Precambrian and the Palaeozoic era, namely the Ediacaran, Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian and Carboniferous periods, i.e. between 635 and 299 Ma. The older rocks in the north of the county display patterns of faulting and folding associated with the Caledonian Orogeny. On the other hand, the late Palaeozoic rocks to the south owe their fold patterns and deformation to the later Variscan Orogeny.

Chapel-le-Dale is west-facing valley in the Yorkshire Dales, England. The U-shaped valley of Chapel-le-Dale is one of the few which drain westwards towards the Irish Sea, however, the river that flows through the valley has several names with the Environment Agency and the Ordnance Survey listing it as the River Doe. However, some older texts insist the name of the watercourse through the dale is the River Greta, which runs from a point below the hamlet of Chapel-le-Dale, and onwards past Ingleton. The dale is sparsely populated with only one settlement, the hamlet of Chapel-le-Dale, which has a small chapel.

References

- Individual sheets of the British Geological Survey's 1:50,000 scale (England and Wales) series of geological maps provide coverage of the area: no's 39, 40, 41, 50, 51, 60 & 61

- ↑ Aitkenhead, N.; Barclay, W. J.; Brandon, A.; Chadwick, R.A.; Chisholm, J.I.; Cooper, A.H.; Johnson, E.W. (2002). British Regional Geology: the Pennines and adjacent areas (4th ed.). Nottingham: British Geological Survey. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0852724241.

- ↑ Stone, P.; Millward, D.; Young, B.; Merritt, J.W.; Clarke, S.M.; McCormac, M.; Lawrence, D.J.D. (2010). British Regional Geology: Northern England (5th ed.). Nottingham: British Geological Survey. pp. 77–80. ISBN 9780852726525.

- ↑ "Geology of Britain Viewer". British Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ Waltham, Tony; Lowe, David, eds. (2013). Caves and Karst of the Yorkshire Dales (First ed.). Buxton: British Cave Research Association. pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-0-900265-46-4.

- ↑ Bentley, John (2005). Ingleton Coalfield. Northern Mine Research Society. ISBN 978-0-901450-58-6.

- ↑ http://www.bgs.ac.uk/Lexicon/lexicon.cfm?pub=APY BGS Lexicon of named rock units: Appleby Gp

- ↑ Goudie, Andrew (1990). The Landforms of England and Wales (1st ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd. p. 128. ISBN 0631173064.

- ↑ Aitkenhead, N.; Barclay, W.J.; Brandon, A.; Chadwick, R.A.; Chisholm, J.I.; Cooper, A.H.; Johnson, E.W. (2002). The Pennines and adjacent areas (Fourth ed.). Keyworth, Nottingham: British Geological Survey. p. 106. ISBN 0-85272-424-1.

- ↑ Goudie, Andrew (1990). The Landforms of England and Wales (1st ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd. pp. 217–229. ISBN 0631173064.

- ↑ "Geoindex Onshore". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ "Radon: the invisible gas that's a bigger killer than carbon monoxide". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2021.