The Echiura, or spoon worms, are a small group of marine animals. Once treated as a separate phylum, they are now considered to belong to Annelida. Annelids typically have their bodies divided into segments, but echiurans have secondarily lost their segmentation. The majority of echiurans live in burrows in soft sediment in shallow water, but some live in rock crevices or under boulders, and there are also deep sea forms. More than 230 species have been described. Spoon worms are cylindrical, soft-bodied animals usually possessing a non-retractable proboscis which can be rolled into a scoop-shape to feed. In some species the proboscis is ribbon-like, longer than the trunk and may have a forked tip. Spoon worms vary in size from less than a centimetre in length to more than a metre.

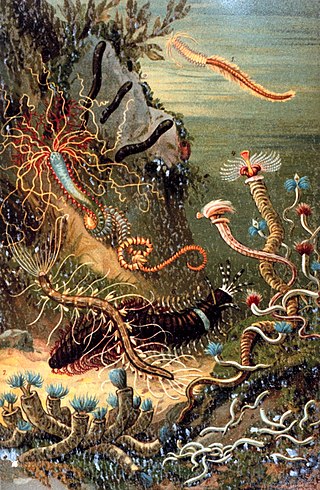

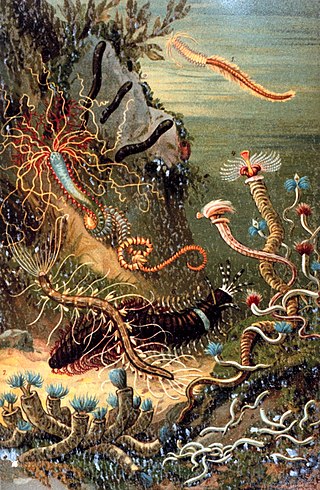

Polychaeta is a paraphyletic class of generally marine annelid worms, commonly called bristle worms or polychaetes. Each body segment has a pair of fleshy protrusions called parapodia that bear many bristles, called chaetae, which are made of chitin. More than 10,000 species are described in this class. Common representatives include the lugworm and the sandworm or clam worm Alitta.

Nereis is a genus of polychaete worms in the family Nereididae. It comprises many species, most of which are marine. Nereis possess setae and parapodia for locomotion and gas exchange. They may have two types of setae, which are found on the parapodia. Acicular setae provide support. Locomotor setae are for crawling, and are the bristles that are visible on the exterior of the Polychaeta. They are cylindrical in shape, found not only in sandy areas, and they are adapted to burrow. They often cling to seagrass (posidonia) or other grass on rocks and sometimes gather in large groups.

Bioturbation is defined as the reworking of soils and sediments by animals or plants. It includes burrowing, ingestion, and defecation of sediment grains. Bioturbating activities have a profound effect on the environment and are thought to be a primary driver of biodiversity. The formal study of bioturbation began in the 1800s by Charles Darwin experimenting in his garden. The disruption of aquatic sediments and terrestrial soils through bioturbating activities provides significant ecosystem services. These include the alteration of nutrients in aquatic sediment and overlying water, shelter to other species in the form of burrows in terrestrial and water ecosystems, and soil production on land.

The Clitellata are a class of annelid worms, characterized by having a clitellum – the 'collar' that forms a reproductive cocoon during part of their life cycles. The clitellates comprise around 8,000 species. Unlike the class of Polychaeta, they do not have parapodia and their heads are less developed.

Epitoky is a process that occurs in many species of polychaete marine worms wherein a sexually immature worm is modified or transformed into a sexually mature worm. Epitokes are pelagic morphs capable of sexual reproduction. Unlike the immature form, which is typically benthic, epitokes are specialized for swimming as well as reproducing. The primary benefit to epitoky is increased chances of finding other members of the same species for reproduction.

Nereididae are a family of polychaete worms. It contains about 500 – mostly marine – species grouped into 42 genera. They may be commonly called ragworms or clam worms.

Alitta virens is an annelid worm that burrows in wet sand and mud. They construct burrows of different shapes They range from being very complex to very simple. Long term burrows are held together by mucus. Their burrows are not connected to each other; they are generally solitary creatures. The spacing between the burrows depends on how readily they can propagate water signals.

Nereis vexillosa belongs to the phylum Annelida, a group known as the segmented worms. It is generally iridescent green and can reach 30 cm in length. It can be distinguished by the size of the upper ligules on the notopodia of the posterior region of the body. The upper ligules are much larger than the lower ligules. It is also without a collar-like structure around the peristomium.

Hesionidae are a family of phyllodocid "Bristle worms". They are marine organisms. Most are found on the continental shelf; Hesiocaeca methanicola is found on methane ice, where it feeds on bacterial biofilms.

Serpula is a genus of sessile, marine annelid tube worms that belongs to the family Serpulidae. Serpulid worms are very similar to tube worms of the closely related sabellid family, except that the former possess a cartilaginous operculum that occludes the entrance to their protective tube after the animal has withdrawn into it. The most distinctive feature of worms of the genus Serpula is their colorful fan-shaped "crown". The crown, used by these animals for respiration and alimentation, is the structure that is most commonly seen by scuba divers and other casual observers.

Alitta succinea is a species of marine annelid in the family Nereididae. It has been recorded throughout the North West Atlantic, as well as in the Gulf of Maine and South Africa.

Phyllodocida is an order of polychaete worms in the subclass Aciculata. These worms are mostly marine, though some are found in brackish water. Most are active benthic creatures, moving over the surface or burrowing in sediments, or living in cracks and crevices in bedrock. A few construct tubes in which they live and some are pelagic, swimming through the water column. There are estimated to be more than 4,600 accepted species in the order.

Platynereis dumerilii is a species of annelid polychaete worm. It was originally placed into the genus Nereis and later reassigned to the genus Platynereis. Platynereis dumerilii lives in coastal marine waters from temperate to tropical zones. It can be found in a wide range from the Azores, the Mediterranean, in the North Sea, the English Channel, and the Atlantic down to the Cape of Good Hope, in the Black Sea, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Sea of Japan, the Pacific, and the Kerguelen Islands. Platynereis dumerilii is today an important lab animal, it is considered as a living fossil, and it is used in many phylogenetic studies as a model organism.

The annelids, also known as the segmented worms, are a large phylum, with over 22,000 extant species including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to various ecologies – some in marine environments as distinct as tidal zones and hydrothermal vents, others in fresh water, and yet others in moist terrestrial environments.

Scolelepis squamata is a species of polychaete worm in the family Spionidae. It occurs on the lower shore of coasts on either side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Dipolydora commensalis is a species of polychaete worm in the family Spionidae. It has a commensal relationship with a hermit crab and occurs on the lower shore of coasts on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Neanthes fucata is a species of marine polychaete worm in the family Nereididae. It lives in association with a hermit crab such as Pagurus bernhardus. It occurs in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean, the North Sea and the Mediterranean Sea.

Tylorrhynchus heterochetus, also known as the Japanese palolo is a species of edible ragworm.