Company history

The decision of W.H. Lever to expand into the Congo was in a period after there had been an international campaign against the Congo Free State from 1890, under the leadership of the British activist E. D. Morel. By 1908, under international pressure, Belgium had annexed the Congo Free State, ending direct personal rule by Leopold II and some of his systems responsible for atrocities, creating the Belgian Congo; but forced labour continued.

The joint-stock company to exploit the oil mills of the Belgian Congo was founded on April 14, 1911, following an agreement by the Minister Jules Renkin and the firm's new President of the Board of directors.

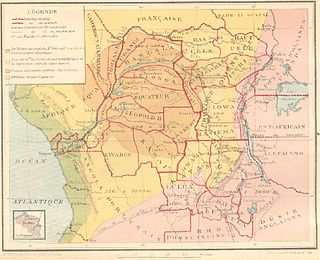

The firm greatly expanded the palm oil business during the Great War. New rail and steamship lines opened to handle the expanded export traffic. [5] The state took over so-called "vacant lands" (land not directly used by local tribes) and redistributed the territory to European companies, to individual white landowners (colons), or to the missions. In this way, an extensive plantation economy developed. The company was allocated 5 state-owned lands for the plantation of Elaeis palms, near five localities: Bumba, (plantation of Alberta) and Barumbu, (plantation of Elisabetha) on the Congo river, Lusanga, (plantations of Leverville) on Kwilu, Basongo on Kasai, Brabanta plantation (Mapangu) and near Ingende, (Flandria plantation) on Ruki. Palm-oil production in the Congo increased from 2,500 tons in 1914 to 9,000 tons in 1921. [6]

As World War II approached, it created the large Elaeis plantation (13,500 hectares) northeast of Bumba on the Aketi road (Yaligimba plantation: 4,000 workers) and two other mixed plantations. Cocoa trees and Heveas in Mokaria (on Yandombo-Basoko road) and Gwaka (on Mongala south of Gemena). Shortly before independence, it will create a tea plantation in Mweso, Kivu.

A research station employing a dozen academics had been established in Yaligimba at the end of the war. Important technological research on machining had been undertaken with other companies in the Mongana pilot plant. DFC also trained, in self-financed schools, their technicians and accountants (in Leverville), their assistant agronomists in Yaeseke, and nurses in Alberta. Major hospitals, managed by doctors, had been established in each plantation. To feed their workers, the DFC had created two large cattle farms, one in the south near Leverville and one in Ubangi in Lombo. The PLCs had a port and storage tanks in Kinshasa, as well as their own boats and their own railcars. They also had a large oil storage capacity in Matadi.

In 1958 the head office was transferred from Brussels to Leopoldville.

In 1957, the company employed 14,780 cutters in Kwilu. Palm Oil production reached 230,000 tons in 1957. [6]

The operations through the subsidiary ceased at Lusanga on Mobutu coming to power in 1965 and the site has fallen to ruin. [7]

Forced labour

Huileries du Congo Belge utilized forced labour. [1] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] Palm cutters failing to meet requirements regarding compulsory cultivation of crops were liable to prison sentences, where the chicotte, a type of whip, was used. [17]

A decree issued 16 March 1922 by the Belgian government in the Congo, which remained in force for the remainder of the colonial period, albeit with a few modifications, made provision for prison sentences of two to three months for "dishonesty" (reneging upon their legal obligations to work), and prison sentences of a fortnight for violations of work discipline. Francois Beissel was dissatisfied with a number of the measures laid down in the decree, and left record of this in a letter dated 22 November 1922, which he wrote to Doctor Albert Duren, Inspector of Industrial Hygiene. Regarding absenteeism, Beissel wrote, "As the man hired could not renege more seriously upon his obligations than by abstaining from work without a plausible excuse, I would venture to hope that the prison sentences recommended would be applied with all due rigor in the case of unjustified, repeated absences. I would be glad to receive some reassurance in this regard." [18]

Reports by Rene Mouchet and Victor Daco show that some limited improvements were made to the condition of the HCB's workers by 1928 and 1929. However, the HCB was still using forced labour. Daco recommended that local workers should be fed just as imported workers were. Accommodations at many camps had been improved, and there were houses made of baked brick or adobe. However some camps, such as the villages of the Yanzi, were still in a deplorable state. Overcrowding continued to be an issue, as houses were too few in number, in Daco's opinion. Daco believed the existing hospitals were in good state, but that there were too few of them, and that the number of beds should be quadrupled. [19]

A report signed on 29 January 1931 by Pierre Ryckmans and two others appointed by the minister discusses the quota system in use by the HCB at the time. Ryckmans' report quoted some directives issued by company headquarters at Leverville for Kwenge sector, dated 23 March 1930. One of the directives stated that, "It is your responsibility to organise the cutters' deliveries so as to obtain on a regular bases an average production of 40 crates per month." Ryckmans recommended that the quotas should vary throughout the year to correlate to the rate at which clusters ripened. The Ryckmans report also stated, "We reckon that the employment of state messengers ought generally to be condemned. They understand just one thing, namely, that they are responsible for getting people to work, and they are ready to use any means possible to carry out this mission." In short, as Jules Marchal summarized the report, "the exploitation of palm groves in Lusanga circle was a system of forced labour pure and simple." [20]