Inkstones can be made from a variety of materials,such as ceramics,lacquered wood,glass,or old bricks. However,they are typically made from stones harvested specifically for inkstone-making. [6] Different stones yield different quality ink;as such,the material of an inkstone is critical to its functionality. Inkstones made from the stones of specific quarries,and from specific caves within those quarries,are highly sought out by collectors. [4] [8]

Quality of inkstones

Two types of rock are mainly used to make inkstones: [1]

- underwater eruptive rocks,such as the famous Chinese duānxī stone (端溪),in Japanese tankei 端渓;

- sedimentary rocks such as shexian stone,in Japanese kyūjū 歙州.

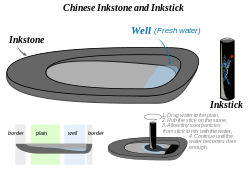

The ink stone consists of a flat part called the “hill”(qiū [丘] or gāng [冈];oka [丘] or [岡] in Japanese),and a hollow part “the sea”,hǎi,海(umi in Japanese) intended to collect the ink created.

An ink stone is most appreciated for the grain,texture or even sound it produces when the Ink stick is rubbed against it in a circular motion:

If you strike the stone hanging on a hook, with a sharp blow with your finger, it should make a beautiful clear sound.” And also: “A good stone is distinguished first and foremost by the fineness and regularity of its grain. It has a softness and mellowness that you feel when you caress it with the palm of your hand. It has a satin sheen. Thanks to these qualities, it picks up the ink as the stick passes over it, accelerating the grinding process and producing fine, dense ink. An infinitesimal part of its grain is also said to pass into the ink, giving it a superior patina. On a stone that is too hard, the stick is not grasped but pushed away, it slips; the grinding is done irregularly and the ink is less beautiful...

The best stones have always come from Chinese quarries on the south bank of the Xijiang in Guangdong. But quarrying these stones was dangerous and strenuous, as they were usually found in caves particularly hard hit by violent floods. Even today, many mines are still in operation, and the oldest stones over a hundred years old, also known as guyàn/ ko-ken (古硯), are much more sought-after than the newer ones known as xinyàn / shin-ken (新硯). Some regions of Japan also produce good quality stones. [1]

A beginner can use very simple stones, which can later be upgraded to higher-quality ink stones as they progress.