This article needs additional citations for verification .(November 2013) |

| Gan | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gann | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 贛語/赣语 Gon nyy | |||||||||||||||||||||

Gan ua (Gan) written in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Native to | China | ||||||||||||||||||||

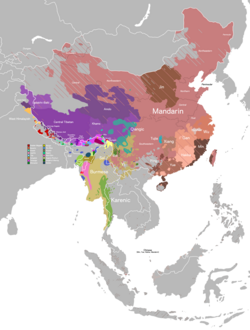

| Region | central and northern Jiangxi, eastern Hunan, eastern Hubei, southern Anhui, northwest Fujian | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | Gan people | ||||||||||||||||||||

Native speakers | 23 million (2021) [1] | ||||||||||||||||||||

Early forms | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Varieties | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese characters Romanization | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Language codes | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 639-3 | gan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Glottolog | ganc1239 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-f | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 贛語 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赣语 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Gan | Gon nyy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Jiangxi dialect | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 江西話 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 江西话 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Gan | Kongsi ua | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Gan,Gann [2] or Kan is a group of Sinitic languages spoken natively by many people in the Jiangxi province of China, as well as significant populations in surrounding regions such as Hunan, Hubei, Anhui, and Fujian. Gan is a member of the Sinitic languages of the Sino-Tibetan language family, and Hakka is the closest Chinese variety to Gan in terms of phonetics.

Contents

- Classification

- Name

- Region

- History

- Antiquity

- Middle Ages

- Late traditional period

- Modern times

- Languages and dialects

- Phonology

- Grammar

- Vocabulary

- Writing system

- See also

- References

- Further reading

- External links

There are different dialects of Gan; the Nanchang dialect is the prestige dialect.