Sino-Tibetan is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. Around 1.4 billion people speak a Sino-Tibetan language. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Sinitic languages. Other Sino-Tibetan languages with large numbers of speakers include Burmese and the Tibetic languages. Four United Nations member states have a Sino-Tibetan language as their main native language. Other languages of the family are spoken in the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif, and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Most of these have small speech communities in remote mountain areas, and as such are poorly documented.

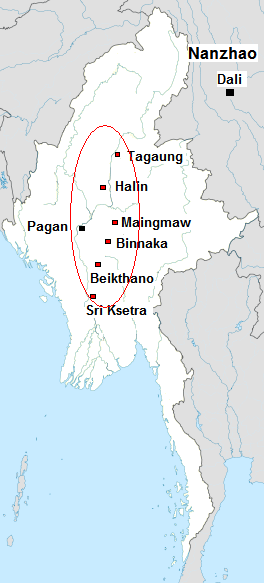

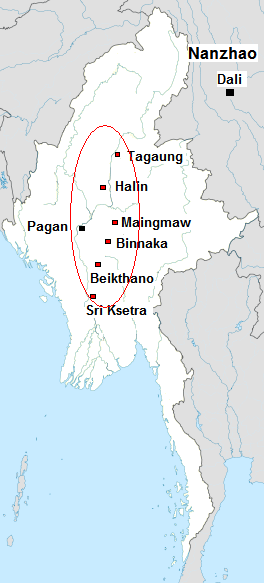

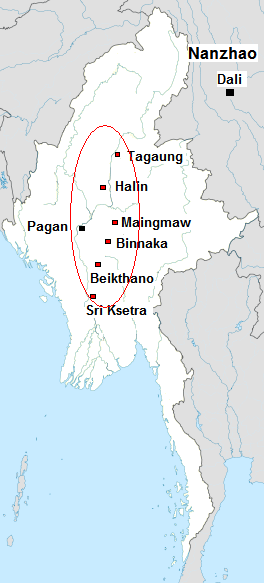

The Pyu city-states were a group of city-states that existed from about the 2nd century BCE to the mid-11th century in present-day Upper Myanmar (Burma). The city-states were founded as part of the southward migration by the Tibeto-Burman-speaking Pyu people, the earliest inhabitants of Burma of whom records are extant. The thousand-year period, often referred to as the Pyu millennium, linked the Bronze Age to the beginning of the classical states period when the Pagan Kingdom emerged in the late 9th century.

Dhammasattha is the Pali name of a genre of literature found in the Indianized kingdoms of Western mainland Southeast Asia principally written in Pali, Burmese, Mon or the Tai languages or in a bilingual nissaya or literal Pali translation. Burmese ဓမ္မသတ် is often transliterated "dhammathat" and the Tai and Mon terms are typically romanized as "thammasāt" or "dhammasāt".

Myazedi inscription, inscribed in 1113, is the oldest surviving stone inscription of the Burmese language. "Myazedi" means "emerald stupa", and the name of the inscription comes from a pagoda located nearby. The inscriptions were made in four languages: Burmese, Pyu, Mon, and Pali, which all tell the story of Prince Yazakumar and King Kyansittha. The primary importance of the Myazedi inscription is that the inscriptions allowed for the deciphering of the written Pyu language.

The kingdom of Pagan was the first Burmese kingdom to unify the regions that would later constitute modern-day Myanmar. Pagan's 250-year rule over the Irrawaddy valley and its periphery laid the foundation for the ascent of Burmese language and culture, the spread of Bamar ethnicity in Upper Myanmar, and the growth of Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar and in mainland Southeast Asia.

Hanlin is a village near Shwebo in the Sagaing Division of Myanmar. In the era of the Pyu city-states it was a city of considerable significance, possibly a local capital replacing Sri Ksetra. Today the modest village is noted for its hot springs and archaeological sites. Hanlin, Beikthano, and Sri Ksetra, the ancient cities of the Pyu Kingdom were built on the irrigated fields of the Dry Zone. They were inscribed by UNESCO on its List of World Heritage Sites in Southeast Asia in May 2014 for their archaeological heritage traced back more than 1,000 years to between 200 BC and 900 AD.

The Burmish languages are a subgroup of the Sino-Tibetan languages consisting of Burmese as well as non-literary languages spoken across Myanmar and South China such as Achang, Lhao Vo, Lashi, and Zaiwa.

Kyansittha was king of the Pagan dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) from 1084 to 1112/13, and is considered one of the greatest Burmese monarchs. He continued the social, economic and cultural reforms begun by his father, King Anawrahta. Pagan became an internationally recognized power during his 28-year reign. The Burmese language and culture continued to gain ground.

Marc Hideo Miyake is an American linguist who specializes in historical linguistics, particularly the study of Old Japanese and Tangut.

Proto-Tibeto-Burman is the reconstructed ancestor of the Tibeto-Burman languages, that is, the Sino-Tibetan languages, except for Chinese. An initial reconstruction was produced by Paul K. Benedict and since refined by James Matisoff. Several other researchers argue that the Tibeto-Burman languages sans Chinese do not constitute a monophyletic group within Sino-Tibetan, and therefore that Proto-Tibeto-Burman was the same language as Proto-Sino-Tibetan.

Old Burmese was an early form of the Burmese language, as attested in the stone inscriptions of Pagan, and is the oldest phase of Burmese linguistic history. The transition to Middle Burmese occurred in the 16th century. The transition to Middle Burmese included phonological changes as well as accompanying changes in the underlying orthography. Word order, grammatical structure and vocabulary have remained markedly comparable, well into Modern Burmese, with the exception of lexical content.

The Pyu script is a writing system used to write the Pyu language, an extinct Sino-Tibetan language that was mainly spoken in present-day central Burma. It was based on the Brahmi-based scripts of both north and south India. The best available evidence suggests that the Pyu script gradually developed between the 2nd and 6th centuries CE. The Pyu script's immediate precursor appears to be the Kadamba script of southwest India. The early period Pyu inscriptions always included interlinear Brahmi scripts. It was not until the 7th and 8th centuries that Sri Ksetra's inscriptions appeared all in the Pyu script, without any interlinear Brahmi.

Sri Ksetra, located along the Irrawaddy River at present-day Hmawza, was once a prominent Pyu settlement. The Pyu occupied several sites across Upper Myanmar, with Sri Ksetra recorded as the largest, the city wall enclosing an area of 1,477 hectares, although a recent survey found it enclosed 1,857 hectares within its monumental brick walls, with an extramural area of a similar size, being the largest Southeast Asian city before Angkor times. Issues surrounding the dating of this site has meant the majority of material is dated between the seventh and ninth centuries AD, however recent scholarship suggests Pyu culture at Sri Ksetra was active centuries before this.

The Early Pagan Kingdom was a city-state that existed in the first millennium CE before the emergence of the Pagan Empire in the mid 11th century. The Burmese chronicles state that the "kingdom" was founded in the second century CE. The seat of power of the small kingdom was first located at Arimaddana, Thiri Pyissaya, and Tampawaddy until 849 CE when it was moved to Pagan (Bagan).

Mruic or Mru–Hkongso is a small group of Sino-Tibetan languages consisting of two languages, Mru and Anu-Hkongso. Their relationship within Sino-Tibetan is unclear.

The Sawlumin inscription is one of the oldest surviving stone inscriptions in Myanmar. The slabs were mainly inscribed in Burmese, Pyu, Mon and Pali, and a few lines in Sanskrit. According to an early analysis, the stele was founded in 1079 by King Saw Lu of Pagan (Bagan).

The Gubyaukgyi temple, located just south of Bagan, Myanmar, in Myinkaba Village, is a Buddhist temple built in 1113 AD by Prince Yazakumar, shortly after the death of his father, King Kyansittha of the Pagan Dynasty. The temple is notable for two reasons. First, it contains a large array of well-preserved frescoes on its interior walls, the oldest original paintings to be found in Bagan. All of the frescoes are accompanied by ink captions written in Old Mon, providing one of the earliest examples of the language's use in Myanmar. Second, the temple is located just to the west of the Myazedi Pagoda, at which was found two stone pillars with inscriptions written in four, ancient Southeast Asian languages: Pali, Old Mon, Old Burmese, and Pyu. The inscription on the pillar displayed by the Myazedi Pagoda has been called the Burmese Rosetta Stone, given its significance both historically and linguistically, as a key to cracking the Pyu language.

A History of the Pyu Alphabet is a book on the Pyu language first published in 1963 by Tha Myat.

Charles Otto Blagden was an English Orientalist and linguist who specialised in the Malay, Mon and Pyu languages. He is particularly known for his studies of Burmese epigraphic inscriptions in the Mon and Pyu scripts.

Lemyethna Temple, also known as Lemyethna Pagoda or the Temple of the Four Faces, is 13th-century Buddhist temple in Bagan, Myanmar. Built in 1222 by the Pagan Empire, the temple remains in regular use.

![]() ; Burmese : ပျူ ဘာသာ, IPA: [pjùbàðà] ; also Tircul language) is an extinct Sino-Tibetan language that was mainly spoken in what is now Myanmar in the first millennium CE. It was the vernacular of the Pyu city-states, which thrived between the second century BCE and the ninth century CE. Its usage declined starting in the late ninth century when the Bamar people of Nanzhao began to overtake the Pyu city-states. The language was still in use, at least in royal inscriptions of the Pagan Kingdom if not in popular vernacular, until the late twelfth century. It became extinct in the thirteenth century, completing the rise of the Burmese language, the language of the Pagan Kingdom, in Upper Burma, the former Pyu realm. [1]

; Burmese : ပျူ ဘာသာ, IPA: [pjùbàðà] ; also Tircul language) is an extinct Sino-Tibetan language that was mainly spoken in what is now Myanmar in the first millennium CE. It was the vernacular of the Pyu city-states, which thrived between the second century BCE and the ninth century CE. Its usage declined starting in the late ninth century when the Bamar people of Nanzhao began to overtake the Pyu city-states. The language was still in use, at least in royal inscriptions of the Pagan Kingdom if not in popular vernacular, until the late twelfth century. It became extinct in the thirteenth century, completing the rise of the Burmese language, the language of the Pagan Kingdom, in Upper Burma, the former Pyu realm. [1]