Related Research Articles

Hakka forms a language group of varieties of Chinese, spoken natively by the Hakka people in parts of Southern China, Taiwan, some diaspora areas of Southeast Asia and in overseas Chinese communities around the world.

Yue is a branch of the Sinitic languages primarily spoken in Southern China, particularly in the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi.

Jiangxi is an inland province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north into hillier areas in the south and east, it shares a border with Anhui to the north, Zhejiang to the northeast, Fujian to the east, Guangdong to the south, Hunan to the west, and Hubei to the northwest.

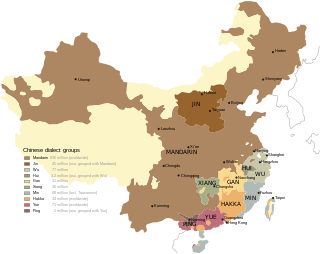

There are hundreds of local Chinese language varieties forming a branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family, many of which are not mutually intelligible. Variation is particularly strong in the more mountainous southeast part of mainland China. The varieties are typically classified into several groups: Mandarin, Wu, Min, Xiang, Gan, Jin, Hakka and Yue, though some varieties remain unclassified. These groups are neither clades nor individual languages defined by mutual intelligibility, but reflect common phonological developments from Middle Chinese.

Gan,Gann or Kan is a group of Sinitic languages spoken natively by many people in the Jiangxi province of China, as well as significant populations in surrounding regions such as Hunan, Hubei, Anhui, and Fujian. Gan is a member of the Sinitic languages of the Sino-Tibetan language family, and Hakka is the closest Chinese variety to Gan in terms of phonetics.

Xiang or Hsiang, also known as Hunanese, is a group of linguistically similar and historically related Sinitic languages, spoken mainly in Hunan province but also in northern Guangxi and parts of neighboring Guizhou, Guangdong, Sichuan, Jiangxi and Hubei provinces. Scholars divided Xiang into five subgroups, Chang-Yi, Lou-Shao, Hengzhou, Chen-Xu and Yong-Quan. Among those, Lou-shao, also known as Old Xiang, still exhibits the three-way distinction of Middle Chinese obstruents, preserving the voiced stops, fricatives, and affricates. Xiang has also been heavily influenced by Mandarin, which adjoins three of the four sides of the Xiang-speaking territory, and Gan in Jiangxi Province, from where a large population immigrated to Hunan during the Ming dynasty.

The Han Chinese people can be defined into subgroups based on linguistic, cultural, ethnic, genetic, and regional features. The terminology used in Mandarin to describe the groups is: "minxi", used in mainland China or "zuqun", used in Taiwan. No Han subgroup is recognized as one of People's Republic of China's 56 official ethnic groups, in Taiwan only three subgroups, Hoklo, Hakka and Waishengren are recognized.

The Sinitic languages, often synonymous with the Chinese languages, are a group of East Asian analytic languages that constitute a major branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. It is frequently proposed that there is a primary split between the Sinitic languages and the rest of the family. This view is rejected by some researchers but has found phylogenetic support among others. The Macro-Bai languages, whose classification is difficult, may be an offshoot of Old Chinese and thus Sinitic; otherwise, Sinitic is defined only by the many varieties of Chinese unified by a shared historical background, and usage of the term "Sinitic" may reflect the linguistic view that Chinese constitutes a family of distinct languages, rather than variants of a single language.

Sichuanese, also called Sichuanese Mandarin, is a branch of Southwestern Mandarin spoken mainly in Sichuan and Chongqing, which was part of Sichuan Province until 1997, and the adjacent regions of their neighboring provinces, such as Hubei, Guizhou, Yunnan, Hunan and Shaanxi. Although "Sichuanese" is often synonymous with the Chengdu-Chongqing dialect, there is still a great amount of diversity among the Sichuanese dialects, some of which are mutually unintelligible with each other. In addition, because Sichuanese is the lingua franca in Sichuan, Chongqing and part of Tibet, it is also used by many Tibetan, Yi, Qiang and other ethnic minority groups as a second language.

The Hangzhou dialect is spoken in the city of Hangzhou, China and its immediate suburbs, but excluding areas further away from Hangzhou such as Xiāoshān (蕭山) and Yúháng (余杭). Its number of speakers has been estimated to be about 1.2 to 1.5 million. It is a dialect of Wu, one of the Chinese varieties.

Chang–Du or Chang–Jing, sometimes called Nanchang or Nanchangese after its principal dialect, is one of the Gan Chinese languages. It is named after Nanchang and Duchang County, and is spoken in those areas as well as in Xinjian, Anyi, Yongxiu, De'an, Xingzi, Hukou, and bordering regions in Jiangxi and in Pingjiang County, Hunan.

The Gan-speaking Chinese or Jiangxi people or Jiangyou people or Kiang-Si people are a subgroup of Han Chinese people. The origin of Gan-speaking people in China are from Jiangxi province in China. Gan-speaking populations are also found in Fujian, southern Anhui and Hubei provinces, and linguistic enclaves are found on Shaanxi, Sichuan, Zhejiang, Hunan, Hainan, Guangdong, Fujian and non-Gan speaking southern and western Jiangxi.

The Fuqing dialect, or Hokchia, is an Eastern Min dialect. It is spoken in the county-level city of Fuqing, China, situated within the prefecture-level city of Fuzhou. It is not completely mutually intelligible with the Fuzhou dialect, although the level of understanding is high enough to be considered so.

The culture of Jiangxi refers to the culture of the people based in or with origins in Jiangxi province, China. It has changed greatly over several millennia, from the land's prehistoric period to its contemporary culture, which incorporates ancient and traditional Chinese culture and modern culture influenced by Western culture.

Differing literary and colloquial readings for certain Chinese characters are a common feature of many Chinese varieties, and the reading distinctions for these linguistic doublets often typify a dialect group. Literary readings are usually used in loanwords, geographic and personal names, literary works such as poetry, and in formal contexts, while colloquial readings are used in everyday vernacular speech.

The Meixian dialect, also known as Moiyan dialect, as well as Meizhou dialect (梅州話), or Jiaying dialect and Gayin dialect, is the prestige dialect of Hakka Chinese. It is named after Meixian District, Meizhou, Guangdong. Sixian dialect is very similar to Meixian dialect.

She or Shehua is an unclassified Sinitic language spoken by the She people of Southeastern China. It is also called Shanha, San-hak (山哈) or Shanhahua (山哈话). She speakers are located mainly in Fujian and Zhejiang provinces of Southeastern China, with smaller numbers of speakers in a few locations of Jiangxi, Guangdong and Anhui provinces.

The Hailu dialect, also known as the Hoiluk dialect or Hailu Hakka, is a dialect of Hakka Chinese that originated in Shanwei, Guangdong. It is also the second most common dialect of Hakka spoken in Taiwan.

The Huizhou dialect is a Chinese dialect spoken in and around Huicheng District, the traditional urban centre of Huizhou, Guangdong. The locals also call the dialect Bendihua and distinguish it from the dialect spoken in Meixian and Danshui, Huiyang, which they call Hakka.

References

- ↑ Wan Bo (萬波), Research on Gan's consonants (贛語聲母的歷史層次研究).

- ↑ Lu Guoyao (魯國堯), On Gan-Hakka and the Tongtai dialect derived from lingua franca of Southern Dynasties (客、贛、通泰方言源於南朝通語說), 2003, ISBN 7-5343-5499-4, pages 123-135

- ↑ Nanshi, volume 37 of Biographies and Collective Biographies (列傳)

- ↑ Du Aiying (杜愛英), On the rhyming system of Jiangxi poets of Song dynasty (宋代江西詩人用韻研究)

- ↑ Liu Lunxin (劉綸鑫), On the history of Gan-Hakka (客贛方言史簡論)

- ↑ DING Bangxin, 1987

- ↑ Furuya Akihiro, 1992