Chinese is a group of languages spoken natively by the ethnic Han Chinese majority and many minority ethnic groups in China. Approximately 1.35 billion people, or 17% of the global population, speak a variety of Chinese as their first language.

Mandarin is a group of Chinese language dialects that are natively spoken across most of northern and southwestern China and Taiwan. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of the phonology of Standard Chinese, the official language of China and Taiwan. Because Mandarin originated in North China and most Mandarin dialects are found in the north, the group is sometimes referred to as Northern Chinese. Many varieties of Mandarin, such as those of the Southwest and the Lower Yangtze, are not mutually intelligible with the standard language. Nevertheless, Mandarin as a group is often placed first in lists of languages by number of native speakers.

Standard Chinese is a modern standard form of Mandarin Chinese that was first codified during the republican era (1912–1949). It is designated as the official language of mainland China and a major language in the United Nations, Singapore, and Taiwan. It is largely based on the Beijing dialect. Standard Chinese is a pluricentric language with local standards in mainland China, Taiwan and Singapore that mainly differ in their lexicon. Hong Kong written Chinese, used for formal written communication in Hong Kong and Macau, is a form of Standard Chinese that is read aloud with the Cantonese reading of characters.

Written vernacular Chinese, also known as baihua, comprises forms of written Chinese based on the vernacular varieties of the language spoken throughout China. It is contrasted with Literary Chinese, which was the predominant written form of the language in imperial China until the early 20th century.

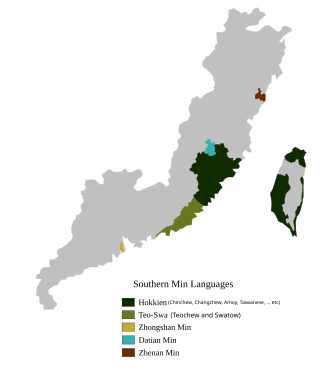

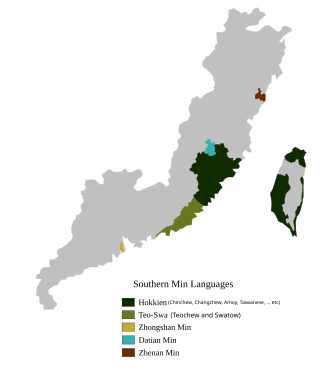

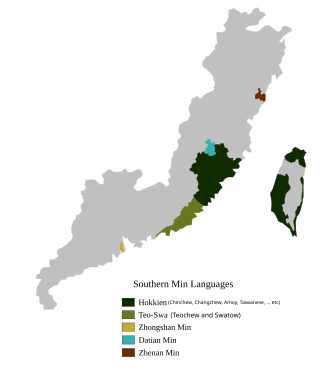

Min is a broad group of Sinitic languages with about 70 million native speakers. These languages are spoken in Fujian province as well as by the descendants of Min-speaking colonists on the Leizhou Peninsula and Hainan and by the assimilated natives of Chaoshan, parts of Zhongshan, three counties in southern Wenzhou, the Zhoushan archipelago, Taiwan and scattered in pockets or sporadically across Hong Kong, Macau, and several countries in Southeast Asia, particularly Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam, Brunei. The name is derived from the Min River in Fujian, which is also the abbreviated name of Fujian Province. Min varieties are not mutually intelligible with one another nor with any other variety of Chinese.

There are hundreds of local Chinese language varieties forming a branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family, many of which are not mutually intelligible. Variation is particularly strong in the more mountainous southeast part of mainland China. The varieties are typically classified into several groups: Mandarin, Wu, Min, Xiang, Gan, Jin, Hakka and Yue, though some varieties remain unclassified. These groups are neither clades nor individual languages defined by mutual intelligibility, but reflect common phonological developments from Middle Chinese.

Penang Hokkien is a local variant of Hokkien spoken in Penang, Malaysia. It is spoken natively by 63.9% of Penang's Chinese community, and also by some Penangite Indians and Penangite Malays.

Cantonese is the traditional prestige variety of Yue Chinese, a Sinitic language belonging to the Sino-Tibetan language family. It originated in the city of Guangzhou and its surrounding Pearl River Delta.

Teochew, also known as Teo-Swa, is a Southern Min language spoken by the Teochew people in the Chaoshan region of eastern Guangdong and by their diaspora around the world. It is sometimes referred to as Chiuchow, its Cantonese rendering, due to English romanization by colonial officials and explorers. It is closely related to Hokkien, as it shares some cognates and phonology with Hokkien.

The Speak Mandarin Campaign is an initiative by the Government of Singapore to encourage the Chinese Singaporean population to speak Standard Mandarin Chinese, one of the four official languages of Singapore. Launched on 7 September 1979 by then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and organised by the Promote Mandarin Council, the SMC has been an annual event promoting the use of Mandarin.

Taiwanese Mandarin, frequently referred to as Guoyu or Huayu, is the variety of Mandarin Chinese spoken in Taiwan. A large majority of the Taiwanese population is fluent in Mandarin, though many also speak a variety of Min Chinese known as Taiwanese Hokkien, which has had a significant influence on the Mandarin spoken on the island.

Malaysian Mandarin is a variety of the Chinese language spoken in Malaysia by ethnic Chinese residents. It is currently the primary language used by the Malaysian Chinese community

Singaporean Hokkien is a local variety of the Hokkien language spoken natively in Singapore. Within Chinese linguistic academic circles, this dialect is known as Singaporean Ban-lam Gu. It bears similarities with the Amoy spoken in Amoy, now better known as Xiamen, as well as Taiwanese Hokkien which is spoken in Taiwan.

Colloquial Singaporean Mandarin, commonly known as Singdarin or Singnese, is a Mandarin dialect native and unique to Singapore similar to its English-based counterpart Singlish. It is based on Mandarin but has a large amount of English and Malay in its vocabulary. There are also words from other Chinese languages such as Cantonese, Hokkien and Teochew as well as Tamil. While Singdarin grammar is largely identical to Standard Mandarin, there are significant divergences and differences especially in its pronunciation and vocabulary.

Hokkien is a variety of the Southern Min languages, native to and originating from the Minnan region, in the southeastern part of Fujian in southeastern mainland China. It is also referred to as Quanzhang, from the first characters of the urban centers of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou.

Singaporean Hokkien is the largest non-Mandarin Chinese dialect spoken in Singapore. As such, it exerts the greatest influence on Colloquial Singaporean Mandarin, resulting in a Hokkien-style Singaporean Mandarin widely spoken in the country.

Standard Singaporean Mandarin is the standard form of Singaporean Mandarin. It is used in all official Chinese media, including all television programs on Channel 8 and Channel U, various radio stations, as well as in Chinese lessons in all Singapore government schools. The written form of Chinese used in Singapore is also based on this standard. Standard Singaporean Mandarin is also the register of Mandarin used by the Chinese elites of Singapore and is easily distinguishable from the Colloquial Singaporean Mandarin spoken by the general populace.

Hokkien, a variety of Chinese that forms part of the Southern Min family and is spoken in Southeastern China, Taiwan and Southeast Asia, does not have a unitary standardized writing system, in comparison with the well-developed written forms of Cantonese and Standard Chinese (Mandarin). In Taiwan, a standard for Written Hokkien has been developed by the Ministry of Education including its Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan, but there are a wide variety of different methods of writing in Vernacular Hokkien. Nevertheless, vernacular works written in Hokkien are still commonly seen in literature, film, performing arts and music.

Mandarin Chinese is the primary formal Chinese language taught academically to students in Chinese Filipino private schools and additionally across other private and public schools, universities, and institutions in the Philippines, especially as the formal written Chinese language.

Hong Kong written Chinese (HKWC) is a local variety of written Chinese used in formal written communication in Hong Kong and Macao. The common Hongkongese name for this form of Chinese is "written language" (書面語), in contrast to the "spoken language" (口語), i.e. Cantonese. While, like other varieties of Written Chinese, it is largely based on Mandarin, it differs from the mainland’s national variety of Standard Chinese (Putonghua) in several aspects, for example that it is written in traditional characters, that its phonology is based on Cantonese, and that its lexicon has English and Cantonese influences. Thus it must not be confused with written Cantonese which, even in Hong Kong, enjoys much less prestige as a literary language than the "written language". The language situation in Hong Kong still reflects the pre-20th century situation of Chinese diglossia where the spoken and literary language differed and the latter was read aloud in the phonology of the respective regional variety instead of a national one.