Yi woman in Yunnan | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 9 million (2010) | |

| 4,827 (2019) [1] | |

| Languages | |

| Yi, Southwestern Mandarin | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Bimoism (native Yi variety of Shamanism); minority: Taoism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tibetan, Bamar (Burman), Nakhi, Qiang, Tujia | |

To further solidify a buffer zone between itself and the expansionistic Nanzhao kingdom, in 846 the Tang bestowed upon the patriarch of the Bole patriclan the hereditary title King of the Luodian kingdom (Luodian guo wang). In the same year the Tang forged a relationship with the Awangren branch of the Mo patriclan, which had settled in the Panxian–Puan area of southwest Guizhou, and recognized the Awangren as leaders of the Yushi kingdom. A year later, in 847, the Tang acknowledged the formation of the Badedian kingdom located in northeast Yunnan and headed by the Mangbu branch of the Azhe patriclan. These four kingdoms, Zangge (Mu'ege), Luodian, Yushi, and Badedian formed an initial Tang defensive perimeter between Nanzhao-controlled territory to the southwest and Tang China. [9]

— John E. Herman

Yunnan kingdoms

Some historians believe that the majority of the kingdom of Nanzhao were of the Bai people, [10] but that the elite spoke a variant of Nuosu (also called Yi), a Tibeto-Burman language closely related to Burmese. [11] The Cuanman people came to power in Yunnan during Zhuge Liang's Southern Campaign in 225. By the fourth century they had gained control of the region, but they rebelled against the Sui dynasty in 593 and were destroyed by a retaliatory expedition in 602. The Cuan split into two groups known as the Black and White Mywa. [12] The White Mywa (Baiman) tribes, who are considered the predecessors of the Bai people, settled on the fertile land of western Yunnan around the alpine fault lake Erhai. The Black Mywa (Wuman), considered to be predecessors of the Yi people, settled in the mountainous regions of eastern Yunnan. These tribes were called Mengshe (蒙舍), Mengxi (蒙嶲), Langqiong (浪穹), Tengtan (邆賧), Shilang (施浪), and Yuexi (越析). Each tribe was known as a zhao. [13] In academia, the ethnic composition of the Nanzhao kingdom's population has been debated for a century. Chinese scholars tend to favour the theory that the rulers came from the aforementioned Bai or Yi groups, while some non-Chinese scholars subscribed to the theory that the Tai ethnic group was a major component, that later moved south into modern-day Thailand and Laos. [14]

In 649, the chieftain of the Mengshe tribe, Xinuluo (細奴邏), founded the Great Meng (大蒙) and took the title of Qijia Wang (奇嘉王; "Outstanding King"). He acknowledged Tang suzerainty. [15] In 652, Xinuluo absorbed the White Mywa realm of Zhang Lejinqiu, who ruled Erhai Lake and Cang Mountain. This event occurred peacefully as Zhang made way for Xinuluo of his own accord. The agreement was consecrated under an iron pillar in Dali. Thereafter the Black and White Mywa acted as warriors and ministers respectively. [13]

In 704 the Tibetan Empire made the White Mywa tribes into vassals or tributaries. [12]

In the year 737 AD, with the support of the Tang dynasty, the great-grandson of Xinuluo, Piluoge (皮羅閣), united the six zhaos in succession, establishing a new kingdom called Nanzhao (Mandarin, "Southern Zhao"). The capital was established in 738 at Taihe, (the site of modern-day Taihe village, a few miles south of Dali). Located in the heart of the Erhai valley, the site was ideal: it could be easily defended against attack and it was in the midst of rich farmland. [16] Under the reign of Piluoge, the White Mywa were removed from eastern Yunnan and resettled in the west. The Black and White Mywa were separated to create a more solidified caste system of ministers and warriors. [13]

Nanzhao existed for 165 years until A.D. 902. After 35 years of tangled warfare, Duan Siping (段思平) of the Bai birth founded the Kingdom of Dali, succeeding the territory of Nanzhao. Most Yi of that time were under the ruling of Dali. Dali's sovereign reign lasted for 316 years until it was conquered by Kublai Khan. During the era of Dali, Yi people lived in the territory of Dali but had little communication with the royalty of Dali.

Kublai Khan included Dali in his domain. The Yuan emperors remained firmly in control of the Yi people and the area they inhabited as part of Kublai Khan's Yunnan Xingsheng (云南行省) at current Yunnan, Guizhou and part of Sichuan. In order to enhance its sovereign over the area, the Yuan dynasty set up a dominion for Yi, Luoluo Xuanweisi (罗罗宣慰司), the name of which means local appeasement government for Lolos. Although technically under the rule of the Yuan emperor, the Yi still had autonomy during the Yuan dynasty. The gulf between aristocrats and the common people increased during this time.

Ming and Qing dynasties

Beginning with the Ming dynasty, the Chinese empire expedited its cultural assimilation policy in Southwestern China, spreading the policy of gaitu guiliu (改土歸流, 'replacing tusi (local chieftains) with "normal" officials'). [17] The governing power of many Yi feudal lords had previously been expropriated by the successors of officials assigned by the central government. With the progress of gaitu guiliu, the Yi area was dismembered into many communities both large and small, and it was difficult for the communities to communicate with each other as there were often Han-ruled areas between them.

The Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty defeated Wu Sangui and took over the land of Yunnan and established a provincial government there. When Ortai became the Viceroy of Yunnan and Guizhou during the era of Yongzheng Emperor, the policy of gaitu guiliu and cultural assimilation against Yi were strengthened. Under these policies, Yi who lived near Kunming were forced to abandon their convention of traditional cremation and adopt burial, a policy which triggered rebellions among the Yi. The Qing dynasty suppressed these rebellions.

After the Second Opium War (1856–1860), many Christian missionaries from France and Great Britain visited the area in which the Yi lived. Although some missionaries believed that Yi of some areas such as Liangshan were not under the ruling of Qing dynasty and should be independent, most aristocrats insisted that Yi was a part of China despite their resentment against Qing rule.

Modern era

Long Yun, a Yi, was the military governor of Yunnan, during the Republic of China rule on mainland China.

The Fourth Front Army of the CCP encountered the Yi people during the Long March and many Yi joined the communist forces. [18]

After the establishment of the PRC, several Yi autonomous administrative districts of prefecture or county level were set up in Sichuan, Yunnan and Guizhou. With the development of automotive traffic and telecommunications, the communications among different Yi areas have been increasing sharply.

Yi people face systematic discrimination and abuse as migrant laborers in contemporary China. [19]

Yi polities throughout history

- Cuanmans

- Mu'ege Kingdom (circa 300–1279), afterwards known as the Chiefdom of Shuixi from 1279 to 1698

- Nanzhao Empire (738–937)

- Luodian Kingdom (羅甸國) of the Bole clan in present-day Luodian County, Yunnan

- Badedian Kingdom of the Mangbu Azhe clan in present-day Zhenxiong [20]

- Luogui Kingdom (羅鬼國) (10th century–1278) in Guizhou

- Ziqi Kingdom (Yushi) (自杞國) (1100–1260) of the Awangren clan in present-day Xingyi, Guizhou

- Kingdom of Shu (1621–1629), a short-lived state during the She-An Rebellion

Language

The Chinese government recognizes six mutually unintelligible Yi languages, from various branches of the Loloish family: [21]

- Northern Yi (Nuosu 诺苏)

- Western Yi (Lalo 腊罗)

- Central Yi (Lolopo 倮倮泼)

- Southern Yi (Nisu 尼苏)

- Southeastern Yi (Sani 撒尼)

- Eastern Yi (Nasu 纳苏)

Northern Yi is the largest with some two million speakers and is the basis of the literary language. It is an analytic language. [22] There are also ethnically Yi languages of Vietnam which use the Yi script, such as Mantsi.

Many Yi in Yunnan, Guizhou and Guangxi know Standard Chinese and code-switching between Yi and Chinese is common.

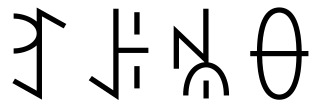

Script

The Yi script was originally logosyllabic like Chinese and dates to at least the 13th century, but seems to be completely independent of any other known script. Until the early 20th century, usage of this script was primarily the domain of bimo priests for transmitting ritual texts from generation to generation. It was not until the mid-twentieth century that elite families in Liangshan began to use the script for non-religious purposes, such as letter writing. [23]

There were perhaps 10,000 characters, many of which were regional, since the script had never been standardized across the Yi peoples. A number of works of history, literature and medicine, as well as genealogies of the ruling families, written in the Old Yi script are still in use and there are Old Yi stone tablets and steles in the area.

An attempt to romanize the script was made in the 1950s but it failed to gain traction. In the 1970s and 1980s, the traditional script was standardized into a syllabary. Syllabic Yi is widely used in books, newspapers, street signs, and education, although with increasing influence from Chinese. [24]

Culture

Gender

Descent and inheritance in Yi society was traditionally patrilineal and men were generally considered superior to women. Men practiced polygamy and levirate marriage. Women were excluded from oral genealogies. [25] In certain locales, Yi women still lag behind men in terms of primary education and very few Yi women become educational instructors or political leaders. Yi women noticeably drank and smoked more than Han Chinese women. [26]

Names

The Yi use a son-father patronymic naming system. The last character of the father's name transfers to become the first character of the son's name. The last character of the son's name is then used as the first character of the grandson's name. A complete Yi name is composed of the clan name, the branch clan name, the father's name, and the person's own name (ex. Aho Bbujji Jjiha Lomusse). Aho is the name of a tribe, Bbuji is the name of a clan, Jjiha is the father's name, and Lomusse is a personal name. The name therefore means Lomusse the son of Jjiha of the Bbujji clan of the Aho tribe. Within the clan he would just be called Lomusse and within the tribe he would be called Jjiha Lomusse. Yi names use the suffixes -sse and -mo to express maleness and femaleness respectively. [27]

This system can also be seen in the names of Nanzhao's rulers: [28]

- Xinuluo

- Luosheng

- Shengluopi

- Piluoge

- Geluofeng

- Fengjiayi

- Yimouxun

- Xungequan

- Quanfengyou – sought to imitate Chinese practices and only went by Fengyou; broke tradition and named his son Shilong [29]

- Shilong

- Longshun

- Shunhuazhen

This is a tradition closely tied to Tibeto-Burman traditions and suggests that the rulers of Nanzhao were not Tai people. [28]

Slavery

Traditional Yi society was divided into four castes, the aristocratic nuohuo/nzymo Black Yi, the commoner qunuo/quho White Yi, the ajia/mgajie, and the xiaxi/gaxy. The Black Yi made up around 7 per cent of the population while the White Yi made up 50 per cent of the population. The two castes did not intermarry and the Black Yi were always considered of higher status than the White Yi, even if the White Yi was wealthier or owned more slaves. The White and Black Yi also lived in separate villages. The Black Yi did not farm, which was traditionally done by White Yi and slaves. Black Yi were responsible only for administration and military activities. The White Yi were not technically slaves but lived as indentured servants to the Black Yi. The Ajia made up 33 per cent of the population. They were owned by both the Black and White Yi and worked as indentured laborers lower than the White Yi. The Xiaxi were the lowest caste. They were slaves who lived with their owners' livestock and had no rights. They could be beaten, sold, and killed for sport. Membership of all four castes was through patrilineal descent. [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] The prevalence of the slave culture was so great that sometimes children were named after how many slaves they owned. For example: Lurbbu (many slaves), Lurda (strong slaves), Lurshy (commander of slaves), Lurnji (origin of slaves), Lurpo (slave lord), Lurha, (hundred slaves), Jjinu (lots of slaves). [27]

Cases of the caste slavery system's influence could be found as late as the 1980s and early 1990s, when nuohuo clans prevented marriage with qunuo or punished members who did. [36]

I once asked a nuoho friend, a highly educated man completely at home in the Chinese scholarly world, what he would do if his daughter, then about fourteen, were to want to marry a quho. He said he would oppose it. I asked him if this were not an old-fashioned attitude. He admitted that it was, but gave two explanations. First, he said, he just wouldn't feel right inside. More important, other nuoho might boycott his family for marrying out, and they would thenceforth have trouble marrying within the nuoho caste. This had happened to some of his affinal relatives in another county.

It is important to point out at the same time, however, that caste stratification in Liangshan has never, as far as I can tell, included notions of pollution or automatic deference, which are so important in the Indian caste system. In areas where there are both nuoho and quho, they socialize freely with one another, eating at each other's houses and often becoming close friends. None of this, however, breaks down the marriage barrier; only among highly educated urbanites is intermarriage ever considered, and then it is usually decided against; most nuoho would rather have their daughters marry a Hxiemga (Han Chinese) than a quho. [37]— Stevan Harrell

Folklore

The most famous hero in Yi mythology is Zhyge Alu. He was the son of a dragon and an eagle who possessed supernatural strength, anti-magic, and anti-ghost powers. He rode a nine-winged flying horse called "long heavenly wings." He also had the help of a magical peacock and python. The magical peacock was called Shuotnyie Voplie and could deafen the ears of those who heard its cry, but if invited into one's house, would consume evil and expel leprosy. The python, called Bbahxa Ayuosse, was defeated by Zhyge Alu, who wrestled with it in the ocean after transforming into a dragon. It was said to be able to detect leprosy, cure tuberculosis, and eradicate epidemics. Like the Chinese mythological archer, Hou Yi, Zhyge Alu shoots down the suns to save the people. [38] In the Yi religion Bimoism, Zhyge Alu aids the bimo priests in curing leprosy and fighting ghosts. [39]

Jiegujienuo was a ghost that caused dizziness, slowness in action, dementia and anxiety. The ghost was blamed for ailments and exorcism rituals were conducted to combat the ghost. The bimo erected small sticks considered to be sacred, the kiemobbur, at the ritual site in preparation. [39]

Torch Festival

The Torch Festival is one of the Yi people's main holidays. According to Yi legend, there were once two men of great strength, Sireabi and Atilaba. Sireabi lived in heaven while Atilaba on earth. When Sireabi heard of Atilaba's strength, he challenged Atilaba to a wrestling match. After suffering two defeats, Sireabi was killed in a bout, which greatly angered the bodhisattavas, who sent a plague of locusts to punish the earth. On the 24th day of the 6th month of the lunar calendar, Atilaba cut down many pine trees and used them as torches to kill the locusts, protecting the crops from destruction. The Torch Festival is thus held in his honor. [40]

Music

The Yi play a number of traditional musical instruments, including large plucked and bowed string instruments, [41] as well as wind instruments called bawu (巴乌) and mabu (马布). The Yi also play the hulu sheng, though unlike other minority groups in Yunnan, the Yi do not play the hulu sheng for courtship or love songs (aiqing). The kouxian, a small four-pronged instrument similar to the Jew's harp, is another commonly found instrument among the Liangshan Yi. Kouxian songs are most often improvised and are supposed to reflect the mood of the player or the surrounding environment. Kouxian songs can also occasionally function in the aiqing form. Yi dance is perhaps the most commonly recognized form of musical performance, as it is often performed during publicly sponsored holidays and/or festival events.

Literature

Artist Colette Fu, great-granddaughter of Long Yun has spent time from 1996 till present photographing the Yi community in Yunnan Province. Her series of pop-up books, titled We are Tiger Dragon People, includes images of many Yi groups. [42] [43]

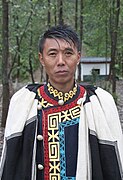

- Yi woman in traditional dress

- Yi woman in traditional dress with a child

- Yi woman in traditional dress

- Yi man in traditional dress

- Yi man in traditional dress

Religion

Bimoism

Other religions

| Yi people | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 彝族 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

In Yunnan, some of the Yi have adopted Buddhism as a result of exchanges with other predominantly Buddhist ethnic groups present in Yunnan, such as the Dai and the Tibetans. The most important god of Yi Buddhism is Mahākāla, a wrathful deity found in Vajrayana and Tibetan Buddhism. In the 20th century, many Yi people in China converted to Christianity, after the arrival of Gladstone Porteous in 1904 and, later, medical missionaries such as Alfred James Broomhall, Janet Broomhall, Ruth Dix and Joan Wales of the China Inland Mission. According to missionary organization OMF International, the exact number of Yi Christians is not known. In 1991 it was reported that there were as many as 1,500,000 Yi Christians in Yunnan Province, especially in Luquan County where there are more than 20 churches.