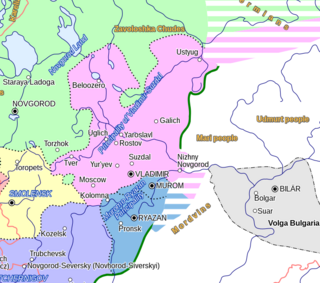

The Mongol Empire invaded and conquered much of Kievan Rus' in the mid-13th century, sacking numerous cities including the largest: Kiev and Chernigov. The siege of Kiev in 1240 by the Mongols is generally held to mark the end of the state of Kievan Rus', which had already been undergoing fragmentation. Many other principalities and urban centres in the northwest and southwest escaped complete destruction or suffered little to no damage from the Mongol invasion, including Galicia–Volhynia, Pskov, Smolensk, Polotsk, Vitebsk, and probably Rostov and Uglich.

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of the Mongol Empire after 1259, it became a functionally separate khanate. It is also known as the Kipchak Khanate or the Ulus of Jochi, and replaced the earlier, less organized Cuman–Kipchak confederation.

Khan is a historic Turkic and Mongolic title originating among nomadic tribes in the Central and Eastern Eurasian Steppe to refer to a king. It first appears among the Rouran and then the Göktürks as a variant of khagan and implied a subordinate ruler. In the Seljük Empire, it was the highest noble title, ranking above malik (king) and emir (prince). In the Mongol Empire it signified the ruler of a horde (ulus), while the ruler of all the Mongols was the khagan or great khan. It is a title commonly used to signify the head of a Pashtun tribe or clan.

Batu Khan was a Mongol ruler and founder of the Golden Horde, a constituent of the Mongol Empire established after Genghis Khan's demise. Batu was a son of Jochi, thus a grandson of Genghis Khan. His ulus ruled over the Kievan Rus', Volga Bulgaria, Cumania, and the Caucasus for around 250 years.

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, extending northward into parts of the Arctic; eastward and southward into parts of the Indian subcontinent, mounted invasions of Southeast Asia, and conquered the Iranian Plateau; and reached westward as far as the Levant and the Carpathian Mountains.

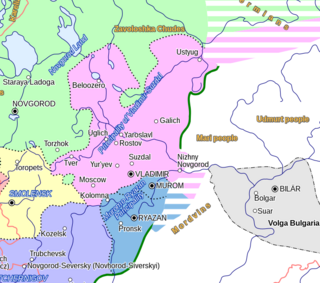

Vladimir-Suzdal, formally known as the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal or Grand Principality of Vladimir (1157–1331), also as Suzdalia or Vladimir-Suzdalian Rus', was one of the major principalities emerging from Kievan Rus' in the late 12th century, centered in Vladimir-on-Klyazma. With time the principality grew into a grand principality divided into several smaller principalities. After being conquered by the Mongol Empire, the principality became a self-governed state headed by its own nobility. A governorship of the principality, however, was prescribed by a jarlig issued from the Golden Horde to a Rurikid sovereign.

Khagan or Qaghan is a title of imperial rank in Turkic, Mongolic, and some other languages, equal to the status of emperor and someone who rules a khaganate (empire). The female equivalent is Khatun.

Bolghar was intermittently the capital of Volga Bulgaria from the 10th to the 13th centuries, along with Bilyar and Nur-Suvar. It was situated on the bank of the Volga River, about 30 km downstream from its confluence with the Kama River and some 130 km from modern Kazan in what is now Spassky District. West of it lies a small modern town, since 1991 known as Bolgar. The UNESCO World Heritage Committee inscribed Bolgar Historical and Archaeological Complex to the World Heritage List in 2014.

Giyasuddin Muhammad Uzbek Khan, better known as Özbeg (1282–1341), was the longest-reigning khan of the Golden Horde (1313–1341), under whose rule the state reached its zenith. He was succeeded by his son Tini Beg. He was the son of Toghrilcha and grandson of Mengu-Timur, who had been khan of the Golden Horde from 1266 to 1280.

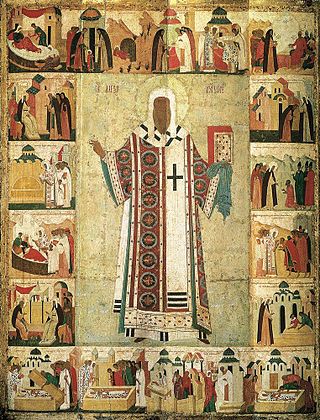

Alexius was Metropolitan of Kiev and all Rus' and presided over the Moscow government during Dmitrii Donskoi's minority.

Öljeyitü Khan, born Temür, also known by his temple name as the Emperor Chengzong of Yuan, was the second emperor of the Yuan dynasty of China, ruling from 10 May 1294 to 10 February 1307. Apart from being the Emperor of China, he is considered as the sixth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, although it was only nominal due to the division of the empire. He was an able ruler of the Yuan dynasty, and his reign established the patterns of power for the next few decades.

Jani Beg, also known as Janibek Khan, was Khan of the Golden Horde from 1342 until his death in 1357. He succeeded his father Öz Beg Khan.

Mengu-Timur or Möngke Temür was a son of Toqoqan Khan and Köchu Khatun of Oirat, the daughter of Toralchi Küregen and granddaughter of Qutuqa Beki. Mengu-Timur was a khan of the Golden Horde, a division of the Mongol Empire in 1266–1280.

A khanate or khaganate is a type of historic polity ruled by a khan, khagan, khatun, or khanum. Khanates were typically nomadic Turkic, Mongol and Tatar societies located on the Eurasian Steppe, politically equivalent in status to kinship-based chiefdoms and feudal monarchies. Khanates and khaganates were organised tribally, where leaders gained power on the support and loyalty of their warrior subjects, gaining tribute from subordinates as realm funding. In comparison to a khanate, a khaganate, the realm of a khagan, was a large nomadic state maintaining subjugation over numerous smaller khanates. The title of khagan, translating as "Khan of the Khans", roughly corresponds in status to that of an emperor.

Tini Beg, also known as Dinibeg, was Khan of the Golden Horde from 1341 to 1342.

Kublai Khan, also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder and first emperor of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. He proclaimed the dynastic name "Great Yuan" in 1271, and ruled Yuan China until his death in 1294.

The Mongols were highly tolerant of most religions during the early Mongol Empire, and typically sponsored several at the same time. At the time of Genghis Khan in the 13th century, virtually every religion had found converts, from Buddhism to Eastern Christianity and Manichaeanism to Islam. To avoid strife, Genghis Khan set up an institution that ensured complete religious freedom, though he himself was a Tengrist. Under his administration, all religious leaders were exempt from taxation, and from public service. Mongol emperors were known for organizing competitions of religious debates among clerics, and these would draw large audiences.

The Tver Uprising of 1327 was the first major uprising against the Golden Horde by the people of Vladimir. It was brutally suppressed by the joint efforts of the Golden Horde, Muscovy and Suzdal. At the time, Muscovy and Vladimir were involved in a rivalry for dominance, and Vladimir's total defeat effectively ended the quarter-century struggle for power.

The division of the Mongol Empire began after Möngke Khan died in 1259 in the siege of Diaoyu Castle with no declared successor, precipitating infighting between members of the Tolui family line for the title of khagan that escalated into the Toluid Civil War. This civil war, along with the Berke–Hulagu war and the subsequent Kaidu–Kublai war, greatly weakened the authority of the great khan over the entirety of the Mongol Empire, and the empire fractured into four khanates: the Golden Horde in Eastern Europe, the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, the Ilkhanate in Iran, and the Yuan dynasty in China based in modern-day Beijing – although the Yuan emperors held the nominal title of khagan of the empire.

Taydula Khatun was a queen consort of the Mongol Golden Horde as the wife of Öz Beg Khan and possibly Nawruz Beg Khan. She was also the mother of the khans Tini Beg and Jani Beg, and the grandmother of Berdi Beg. The favorite of her husband, she gained and retained a lasting importance during the reigns of her sons and grandson, and attempted to hold on to power by appointing the latter's successors.