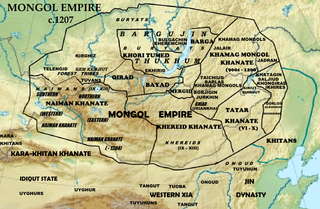

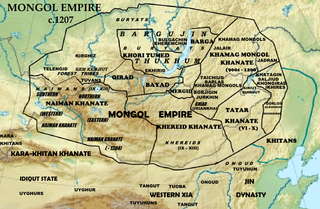

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of the Mongol Empire after 1259, it became a functionally separate khanate. It is also known as the Kipchak Khanate or the Ulus of Jochi, and replaced the earlier, less organized Cuman–Kipchak confederation.

The Mongolic languages are a language family spoken by the Mongolic peoples in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, North Asia and East Asia, mostly in Mongolia and surrounding areas and in Kalmykia and Buryatia. The best-known member of this language family, Mongolian, is the primary language of most of the residents of Mongolia and the Mongol residents of Inner Mongolia, with an estimated 5.7+ million speakers.

Batu Khan was a Mongol ruler and founder of the Golden Horde, a constituent of the Mongol Empire established after Genghis Khan's demise. Batu was a son of Jochi, thus a grandson of Genghis Khan. His ulus ruled over the Kievan Rus', Volga Bulgaria, Cumania, and the Caucasus for around 250 years.

A kurultai was a political and military council of ancient Mongol and Turkic chiefs and khans.

Giovanni da Pian del CarpineOFM was a medieval Italian diplomat, Catholic archbishop, explorer and one of the first Europeans to enter the court of the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire. He was the author of the earliest important Western account of northern and Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and other regions of the Mongol dominion. He served as the Primate of Serbia, based in Antivari, from 1247 to 1252.

Tarkhan is an ancient Central Asian title used by various Turkic, Hungarian, Mongolic, and Iranian peoples. Its use was common among the successors of the Mongol Empire and Turkic Khaganate.

Güyük Khan or Güyüg Khagan, mononymously Güyüg, was the third Khagan of the Mongol Empire, the eldest son of Ögedei Khan and a grandson of Genghis Khan. He reigned from 1246 to 1248. He started his military career by participating in the conquest of Eastern Xia in China and later in the invasion of Europe. When his father died, he was enthroned as Khagan in 1246. During his almost two year reign, he reversed some of his mother's unpopular edicts and ordered an empire-wide census; he also held some authority in Eastern Europe, appointing Andrey II as the grand prince of Vladimir and giving the princely title of Kiev to Alexander Nevsky.

William of Rubruck or Guillaume de Rubrouck was a Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer.

The Blue Horde was a crucial component of the Mongol Empire established after Genghis Khan's demise in 1227. Functioning as the western part of the split Golden Horde, it contrasted with the White Horde's eastern segment, adhering to the Mongolian and Turkic tradition of cardinal direction colors.

The Mongol invasion of Volga Bulgaria lasted from 1223 to 1236. The Bulgar state, centered in lower Volga and Kama, was the center of the fur trade in Eurasia throughout most of its history. Before the Mongol conquest, Russians of Novgorod and Vladimir repeatedly looted and attacked the area, thereby weakening the Bulgar state's economy and military power. The latter ambushed the Mongols in the later 1223 or in 1224. Several clashes occurred between 1229–1234, and the Mongol Empire conquered the Bulgars in 1236.

Berke Khan was a grandson of Genghis Khan from his son Jochi and a Mongol military commander and ruler of the Golden Horde, a division of the Mongol Empire, who effectively consolidated the power of the Blue Horde and White Horde from 1257 to 1266. He succeeded his brother Batu Khan of the Blue Horde (West), and was responsible for the first official establishment of Islam in a khanate of the Mongol Empire. Following the Sack of Baghdad by Hulagu Khan, his cousin and head of the Mongol Ilkhanate based in Persia, he allied with the Egyptian Mamluks against Hulagu. Berke also supported Ariq Böke against Kublai in the Toluid Civil War, but did not intervene militarily in the war because he was occupied in his own war against Hulagu and the Ilkhanate.

Simon of Saint-Quentin was a Dominican friar and diplomat who accompanied Ascelin of Lombardia on an embassy which Pope Innocent IV sent to the Mongols in 1245. Simon’s account of the mission, in its original form, is lost; but a large section has been preserved in Vincent of Beauvais’ Speculum Historiale, where nineteen chapters are expressly said to be ex libello fratris Simonis. The embassy of Ascelin and Simon proceeded to the camp of Baiju at Sitiens in Armenia, lying between the Aras River and Lake Sevan, fifty-nine days' journey from Acre.

The Ongud were a Turkic tribe that later became Mongolized active in what is now Inner Mongolia in northern China around the time of Genghis Khan (1162–1227). Many Ongud were members of the Church of the East. They lived in an area lining the Great Wall in the northern part of the Ordos Plateau and territories to the northeast of it. They appear to have had two capitals, a northern one at the ruin known as Olon Süme and another a bit to the south at a place called Koshang or Dongsheng. They acted as wardens of the marches for the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) to the north of Shanxi.

Ystoria Mongalorum is a report, compiled by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, of his trip to the Mongol Empire. Written in the 1240s, it is the oldest European account of the Mongols. Giovanni was the first European to try to chronicle Mongol history.

A khanate or khaganate is a type of historic polity ruled by a khan, khagan, khatun, or khanum. Khanates were typically nomadic Turkic, Mongol and Tatar societies located on the Eurasian Steppe, politically equivalent in status to kinship-based chiefdoms and feudal monarchies. Khanates and khaganates were organised tribally, where leaders gained power on the support and loyalty of their warrior subjects, gaining tribute from subordinates as realm funding. In comparison to a khanate, a khaganate, the realm of a khagan, was a large nomadic state maintaining subjugation over numerous smaller khanates. The title of khagan, translating as "Khan of the Khans", roughly corresponds in status to that of an emperor.

Saray-Jük, was a medieval city on the border between Europe and Asia. It was located 50 km north Atyrau on the lower Ural River, near the modern village of Sarayshyq, Atyrau Region, Kazakhstan. The city lay on an important trade route between Europe and China and flourished between the 10th and 16th centuries.

The Wings of the Golden Horde were subdivisions of the Golden Horde in the 13th to 15th centuries CE. Jochi, the eldest son of the Mongol Empire founder Genghis Khan, had several sons who inherited Jochi's dominions as fiefs under the rule of two of the brothers, Batu Khan and the elder Orda Khan who agreed that Batu enjoyed primacy as the supreme khan of the Golden Horde.

The Mongol invasion of Circassia and Alania refers to the invasion of Circassia and Alania by the Mongolian Empire. During the 13th and 14th centuries, the Mongols launched massive invasions of the territory of Circassia and Alania. William of Rubruck, who travelled to the Caucasus in 1253, wrote that the Circassians had never "bowed to Mongol rule", despite the fact that a whole fifth of the Mongol armies were at that time devoted to the task of crushing the Alano-Circassian resistance. Circassians and Alans made use of both the forests and the mountains, and waged a successful guerrilla war, maintaining their freedom to some extent.