Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Confucianism developed from teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE), during a time that was later referred to as the Hundred Schools of Thought era. Confucius considered himself a transmitter of cultural values inherited from the Xia (c. 2070–1600 BCE), Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) and Western Zhou (c. 1046–771 BCE) dynasties. Confucianism was suppressed during the Legalist and autocratic Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), but survived. During the Han dynasty, Confucian approaches edged out the "proto-Taoist" Huang–Lao as the official ideology, while the emperors mixed both with the realist techniques of Legalism.

Chinese philosophy originates in the Spring and Autumn period and Warring States period, during a period known as the "Hundred Schools of Thought", which was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments. Although much of Chinese philosophy begun in the Warring States period, elements of Chinese philosophy have existed for several thousand years. Some can be found in the I Ching, an ancient compendium of divination, which dates back to at least 672 BCE.

Confucius, born Kong Qiu (孔丘), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the philosophy and teachings of Confucius. His philosophical teachings, called Confucianism, emphasized personal and governmental morality, harmonious social relationships, righteousness, kindness, sincerity, and a ruler's responsibilities to lead by virtue.

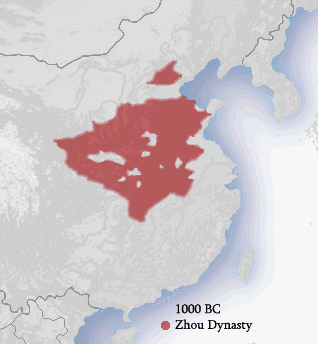

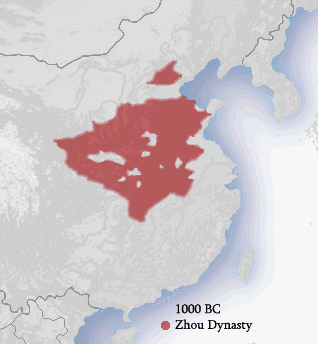

The Zhou dynasty was a royal dynasty of China that existed for 789 years from c. 1046 BC until 256 BC, the longest of all dynasties in Chinese history. During the Western Zhou period, the royal house, surnamed Ji, had military control over ancient China. Even as Zhou suzerainty became increasingly ceremonial over the following Eastern Zhou period (771–256 BC), the political system created by the Zhou royal house survived in some form for several additional centuries. A date of 1046 BC for the Zhou's establishment is supported by the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project and David Pankenier, but David Nivison and Edward L. Shaughnessy date the establishment to 1045 BC.

Sinocentrism refers to a worldview that China is the cultural, political, or economic center of the world. Sinocentrism was a core concept in various Chinese dynasties. The Chinese considered themselves to be "all-under-Heaven", ruled by the emperor, known as Son of Heaven. Those that lived outside of the Huaxia were regarded as "barbarians". In addition, states outside of China, such as Japan or Korea, were considered to be vassals of China.

Korean Confucianism is the form of Confucianism that emerged and developed in Korea. One of the most substantial influences in Korean intellectual history was the introduction of Confucian thought as part of the cultural influence from China.

Neo-Confucianism is a moral, ethical, and metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, which originated with Han Yu (768–824) and Li Ao (772–841) in the Tang dynasty, and became prominent during the Song and Ming dynasties under the formulations of Zhu Xi (1130–1200). After the Mongol conquest of China in the thirteenth century, Chinese scholars and officials restored and preserved neo-Confucianism as a way to safeguard the cultural heritage of China.

New Confucianism is an intellectual movement of Confucianism that began in the early 20th century in Republican China, and further developed in post-Mao era contemporary China. It primarily developed during the May Fourth Movement. It is deeply influenced by, but not identical with, the neo-Confucianism of the Song and Ming dynasties.

For most of its history, China was organized into various dynastic states under the rule of hereditary monarchs. Beginning with the establishment of dynastic rule by Yu the Great c. 2070 BC, and ending with the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor in AD 1912, Chinese historiography came to organize itself around the succession of monarchical dynasties. Besides those established by the dominant Han ethnic group or its spiritual Huaxia predecessors, dynasties throughout Chinese history were also founded by non-Han peoples.

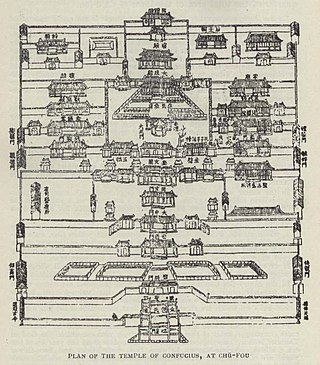

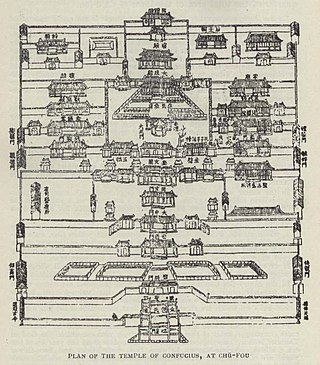

A temple of Confucius or Confucian temple is a temple for the veneration of Confucius and the sages and philosophers of Confucianism in Chinese folk religion and other East Asian religions. They were formerly the site of the administration of the imperial examination in China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam and often housed schools and other studying facilities.

The Four Books and Five Classics are authoritative and important books associated with Confucianism, written before 300 BC. They are traditionally believed to have been either written, edited or commented by Confucius or one of his disciples. Starting in the Han dynasty, they became the core of the Chinese classics on which students were tested in the Imperial examination system.

The Duke Yansheng, literally "Honorable Overflowing with Wisdom", sometimes translated as Holy Duke of Yen, was a Chinese title of nobility. It was originally created as a marquis title in the Western Han dynasty for a direct descendant of Confucius.

Han learning, or the Han school of classical philology, was an intellectual movement that reached its height in the middle of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) in China. The focus of the movement was to reject neo-Confucianism in order to return to a study of the original Confucian texts.

During the late Zhou dynasty, the inhabitants of the Central Plains began to make a distinction between Hua and Yi, referred to by some historians as the Sino–barbarian dichotomy. They defined themselves as part of cultural and political region known as Huaxia, which they contrasted with the surrounding regions home to outsiders, conventionally known as the Four Barbarians. Although Yi is usually translated as "barbarian", other translations of this term in English include "foreigners", "ordinary others", "wild tribes" and "uncivilized tribes". The Hua–Yi distinction asserted Chinese superiority, but implied that outsiders could become Hua by adopting their culture and customs. The Hua–Yi distinction was not unique to China, but was also applied by various Vietnamese, Japanese, and Koreans regimes, all of whom considered themselves at one point in history to be legitimate successors to the Chinese civilization and the "Central State" in imitation of China.

Shenyi, also called Deep garment in English, means "wrapping the body deep within the clothes" or "to wrap the body deep within cloth". The shenyi is an iconic form of robe in Hanfu, which was recorded in Liji and advocated in Zhu Xi's Zhuzi jiali《朱子家禮》. As cited in the Liji, the shenyi is a long robe which is created when the "upper half is connected to the bottom half to cover the body fully". The shenyi, along with its components, existed prior to the Zhou dynasty and appeared at least since the Shang dynasty. The shenyi was then developed in Zhou dynasty with a complete system of attire, being shaped by the Zhou dynasty's strict hierarchical system in terms of social levels, gender, age, and situation and was used as a basic form of clothing. The shenyi then became the mainstream clothing choice during the Qin and Han dynasties. By the Han dynasty, the shenyi had evolved into two types of robes: the qujupao and the zhijupao. The shenyi later gradually declined in popularity around the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern dynasties period. However, the shenyi's influence persisted in the following dynasties. The shenyi then became a form of formal wear for scholar-officials in the Song and Ming dynasties. Chinese scholars also recorded and defined the meaning of shenyi since the ancient times, such as Zhu Xi in the Song dynasty, Huang Zongxi in the Ming dynasty, and Jiang Yong in the Qing dynasty.

Yan Hui was a Chinese philosopher. He was the favorite disciple of Confucius and one of the most revered figures of Confucianism. He is venerated in Confucian temples as one of the Four Sages.

Edo Neo-Confucianism, known in Japanese as Shushi-Gaku, refers to the schools of Neo-Confucian philosophy that developed in Japan during the Edo period. Neo-Confucianism reached Japan during the Kamakura period. The philosophy can be characterized as humanistic and rationalistic, with the belief that the universe could be understood through human reason, and that it was up to man to create a harmonious relationship between the universe and the individual. The 17th-century Tokugawa shogunate adopted Neo-Confucianism as the principle of controlling people and Confucian philosophy took hold. Neo-Confucians such as Hayashi Razan and Arai Hakuseki were instrumental in the formulation of Japan's dominant early modern political philosophy.

The Study of Current Script Texts is a school of thought in Confucianism that was based on Confucian classics recompiled in the early Han dynasty by Confucians who survived the burning of books and burying of scholars during the Qin dynasty. The survivors wrote the classics in the contemporary characters of their time, and these texts were later dubbed as "Current Script" 今文. Current Script school attained prominence in the Western Han dynasty and became the official interpretation for Confucianism, which was adopted as the official ideology by Emperor Wu of Han.

Religious Confucianism is an interpretation of Confucianism as a religion. It originated in the time of Confucius with his defense of traditional religious institutions of his time such as the Jongmyo rites, and the ritual and music system.

The Chinese ritual and music system is a social system that originated in the Zhou dynasty to maintain the social order. Together with the patriarchal system, it constituted the social system of the entire ancient China and had a great influence on the politics, culture, art and thought of later generations. The feudal system and the Well-field system were two other institutions that developed at that time. According to legend it was founded by the Duke of Zhou and King Wu of Zhou.