John Hancock was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He is remembered for his large and stylish signature on the United States Declaration of Independence, so much so that the term John Hancock or Hancock has become a nickname in the United States for one's signature. He also signed the Articles of Confederation, and used his influence to ensure that Massachusetts ratified the United States Constitution in 1788.

The Boston Massacre was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which a group of nine British soldiers shot five people out of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing them verbally and throwing various projectiles. The event was heavily publicized as "a massacre" by leading Patriots such as Paul Revere and Samuel Adams. British troops had been stationed in the Province of Massachusetts Bay since 1768 in order to support crown-appointed officials and to enforce unpopular Parliamentary legislation.

Thomas Hutchinson was a businessman, historian, and a prominent Loyalist politician of the Province of Massachusetts Bay in the years before the American Revolution. He has been referred to as "the most important figure on the loyalist side in pre-Revolutionary Massachusetts". He was a successful merchant and politician, and was active at high levels of the Massachusetts government for many years, serving as lieutenant governor and then governor from 1758 to 1774. He was a politically polarizing figure who came to be identified by John Adams and Samuel Adams as a proponent of hated British taxes, despite his initial opposition to Parliamentary tax laws directed at the colonies. He was blamed by Lord North for being a significant contributor to the tensions that led to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War.

Sir Francis Bernard, 1st Baronet was a British colonial administrator who served as governor of the provinces of New Jersey and Massachusetts Bay. His uncompromising policies and harsh tactics in Massachusetts angered the colonists and were instrumental in the building of broad-based opposition within the province to the rule of Parliament in the events leading to the American Revolution.

James Bowdoin II was an American political and intellectual leader from Boston, Massachusetts, during the American Revolution and the following decade. He initially gained fame and influence as a wealthy merchant. He served in both branches of the Massachusetts General Court from the 1750s to the 1770s. Although he was initially supportive of the royal governors, he opposed British colonial policy and eventually became an influential advocate of independence. He authored a highly political report on the 1770 Boston Massacre that has been described by historian Francis Walett as one of the most influential pieces of writing that shaped public opinion in the colonies.

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in British America which became one of the thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III and Mary II, the joint monarchs of the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland. The charter took effect on May 14, 1692, and included the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Plymouth Colony, the Province of Maine, Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick; the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the direct successor. Maine has been a separate state since 1820, and Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are now Canadian provinces, having been part of the colony only until 1697.

The Townshend Acts or Townshend Duties, were a series of British acts of Parliament passed during 1767 and 1768 introducing a series of taxes and regulations to fund administration of the British colonies in America. They are named after the Chancellor of the Exchequer who proposed the program. Historians vary slightly as to which acts they include under the heading "Townshend Acts", but five are often listed:

Thomas Cushing III was an American lawyer, merchant, and statesman from Boston, Massachusetts. Active in Boston politics, he represented the city in the provincial assembly from 1761 to its dissolution in 1774, serving as the lower house's speaker for most of those years. Because of his role as speaker, his signature was affixed to many documents protesting British policies, leading officials in London to consider him a dangerous radical. He engaged in extended communications with Benjamin Franklin who at times lobbied on behalf of the legislature's interests in London, seeking ways to reduce the rising tensions of the American Revolution.

The Stamp Act Congress, also known as the Continental Congress of 1765, was a meeting held in New York, New York, consisting of representatives from some of the British colonies in North America. It was the first gathering of elected representatives from several of the American colonies to devise a unified protest against new British taxation. Parliament had passed the Stamp Act, which required the use of specialty stamped paper for legal documents, playing cards, calendars, newspapers, and dice for virtually all business in the colonies starting on November 1, 1765.

Faneuil Hall is a marketplace and meeting hall located near the waterfront and today's Government Center, in Boston, Massachusetts. Opened in 1742, it was the site of several speeches by Samuel Adams, James Otis, and others encouraging independence from Great Britain. It is now part of Boston National Historical Park and a well-known stop on the Freedom Trail. It is sometimes referred to as "the Cradle of Liberty", though the building and location have ties to slavery.

The committees of correspondence were, prior to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, a collection of American political organizations that sought to coordinate opposition to British Parliament and, later, support for American independence. The brainchild of Samuel Adams, a Patriot from Boston, the committees sought to establish, through the writing of letters, an underground network of communication among Patriot leaders in the Thirteen Colonies. The committees were instrumental in setting up the First Continental Congress, which met in Philadelphia.

The Massachusetts Circular Letter was a statement written by Samuel Adams and James Otis Jr., and passed by the Massachusetts House of Representatives in February 1768 in response to the Townshend Acts. Reactions to the letter brought heightened tensions between the British Parliament and Massachusetts, and resulted in the military occupation of Boston by the British Army, which contributed to the coming of the American Revolution.

The Boston Gazette (1719–1798) was a newspaper published in Boston, in the British North American colonies. It was a weekly newspaper established by William Brooker, who was just appointed Postmaster of Boston, with its first issue released on December 21, 1719. The Boston Gazette is widely considered the most influential newspaper in early American history, especially in the years leading up to and into the American Revolution. In 1741 the Boston Gazette incorporated the New-England Weekly Journal, founded by Samuel Kneeland, and became the Boston-Gazette, or New-England Weekly Journal. Contributors included: Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, Phyllis Wheatley.

The Journal of Occurrences, also known as Journal of the Times and Journal of Transactions in Boston, was a series of newspaper articles published from 1768 to 1769 in the New York Journal and Packet and other newspapers, chronicling the occupation of Boston by the British Army. Authorship of the articles was anonymous, but is usually attributed to Samuel Adams, then the clerk of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. William Cooper, Boston's town clerk, has also been named as a possible author. The articles may have been written by a group of people working in collaboration.

The Hutchinson Letters affair was an incident that increased tensions between the colonists of the Province of Massachusetts Bay and the British government prior to the American Revolution.

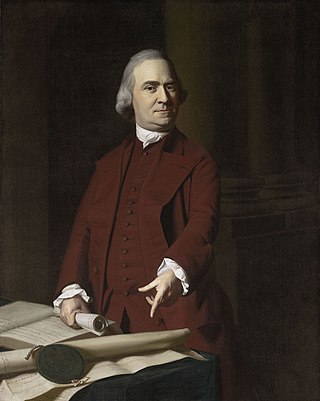

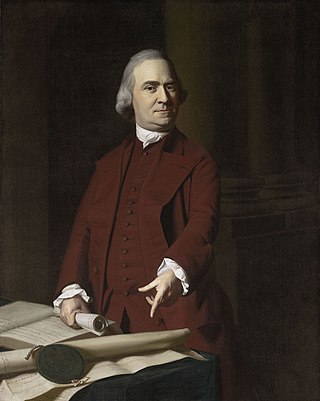

Samuel Adams was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, and one of the architects of the principles of American republicanism that shaped the political culture of the United States. He was a second cousin to his fellow Founding Father, President John Adams.

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress (1774–1780) was a provisional government created in the Province of Massachusetts Bay early in the American Revolution. Based on the terms of the colonial charter, it exercised de facto control over the rebellious portions of the province, and after the British withdrawal from Boston in March 1776, the entire province. When Massachusetts Bay declared its independence in 1776, the Congress continued to govern under this arrangement for several years. Increasing calls for constitutional change led to a failed proposal for a constitution produced by the Congress in 1778, and then a successful constitutional convention that produced a constitution for the state in 1780. The Provincial Congress came to an end with elections in October 1780.

James Otis Jr. was an American lawyer, political activist, colonial legislator, and early supporter of patriotic causes in Massachusetts at the beginning of the Revolutionary Era. Otis was a fervent opponent of the writs of assistance imposed by Great Britain on the American colonies in the early 1760s that allowed law enforcement officials to search property without cause. He later expanded his criticism of British authority to include tax measures that were being enacted by Parliament. As a result, Otis is often incorrectly credited with coining the slogan "taxation without representation is tyranny".

Merchants Row in Boston, Massachusetts is a short street extending from State Street to Faneuil Hall Square in the Financial District. Since the 17th century it has been a place of commercial activity. It sits close to Long Wharf and Dock Square, hubs of shipping and trade through the 19th century. Portions of the street were formerly known as Swing-Bridge Lane, Fish Lane, and Roebuck Passage.

Ezekiel Goldthwait (1710–1782) was a wealthy businessman and landowner in colonial Boston, Massachusetts. He was one of the foremost citizens and prominent in the town's affairs in the years leading up to the American Revolution.