Chondrichthyes is a class of jawed fish that contains the cartilaginous fish or chondrichthyians, which all have skeletons primarily composed of cartilage. They can be contrasted with the Osteichthyes or bony fish, which have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. Chondrichthyes are aquatic vertebrates with paired fins, paired nares, placoid scales, conus arteriosus in the heart, and a lack of opecula and swim bladders. Within the infraphylum Gnathostomata, cartilaginous fishes are distinct from all other jawed vertebrates.

Gnathostomata are the jawed vertebrates. Gnathostome diversity comprises roughly 60,000 species, which accounts for 99% of all living vertebrates, including humans. In addition to opposing jaws, living gnathostomes have true teeth, paired appendages, the elastomeric protein of elastin, and a horizontal semicircular canal of the inner ear, along with physiological and cellular anatomical characters such as the myelin sheaths of neurons, and an adaptive immune system that has the discrete lymphoid organs of spleen and thymus, and uses V(D)J recombination to create antigen recognition sites, rather than using genetic recombination in the variable lymphocyte receptor gene.

Sarcopterygii — sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii — is a taxon of the bony fish known as the lobe-finned fish or sarcopterygians, characterised by prominent muscular buds (lobes) within the fins, which are supported by appendicular skeletons. This is in contrast to the other clade of bony fish, the Actinopterygii, which have only skin-covered bony spines (lepidotrichia) supporting the fins and has no major skeleton within the fins.

The jaws are a pair of opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term jaws is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serving to open and close it and is part of the body plan of humans and most animals.

Placodermi is a class of armoured prehistoric fish, known from fossils, which lived from the Silurian to the end of the Devonian period. Their head and thorax were covered by articulated armoured plates and the rest of the body was scaled or naked, depending on the species. Placoderms were among the first jawed fish; their jaws likely evolved from the first of their gill arches.

Teleostomi is an obsolete clade of jawed vertebrates that supposedly includes the tetrapods, bony fish, and the wholly extinct acanthodian fish. Key characters of this group include an operculum and a single pair of respiratory openings, features which were lost or modified in some later representatives. The teleostomes include all jawed vertebrates except the chondrichthyans and the extinct class Placodermi.

Arthrodira is an order of extinct armored, jawed fishes of the class Placodermi that flourished in the Devonian period before their sudden extinction, surviving for about 50 million years and penetrating most marine ecological niches. Arthrodires were the largest and most diverse of all groups of placoderms.

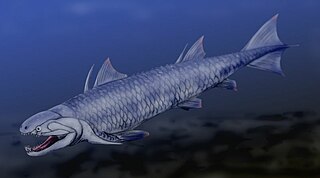

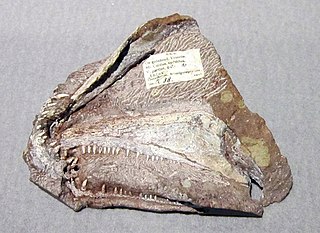

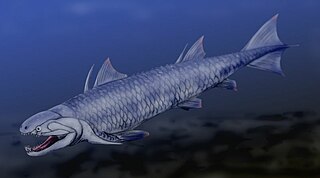

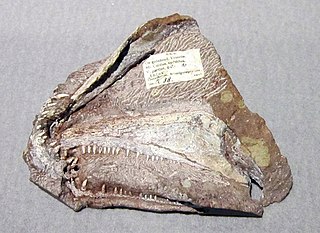

Rhizodontida is an extinct group of predatory tetrapodomorphs known from many areas of the world from the Givetian through to the Pennsylvanian - the earliest known species is about 377 million years ago (Mya), the latest around 310 Mya. Rhizodonts lived in tropical rivers and freshwater lakes and were the dominant predators of their age. They reached huge sizes - the largest known species, Rhizodus hibberti from Europe and North America, was an estimated 7 m in length, making it the largest freshwater fish known.

Psarolepis is a genus of extinct bony fish which lived around 397 to 418 million years ago. Fossils of Psarolepis have been found mainly in South China and described by paleontologist Xiaobo Yu in 1998. It is not known certainly in which group Psarolepis belongs, but paleontologists agree that it probably is a basal genus and seems to be close to the common ancestor of lobe-finned and ray-finned fishes. In 2001, paleontologist John A. Long compared Psarolepis with onychodontiform fishes and refer to their relationships.

Eusthenodon is an extinct genus of tristichopterid tetrapodomorphs from the Late Devonian period, ranging between 383 and 359 million years ago. They are well known for being a cosmopolitan genus with remains being recovered from East Greenland, Australia, Central Russia, South Africa, Pennsylvania, and Belgium. Compared to the other closely related genera of the Tristichopteridae clade, Eusthenodon was one of the largest lobe-finned fishes and among the most derived tristichopterids alongside its close relatives Cabonnichthys and Mandageria.

Tristichopterus, with a maximum length of sixty centimetres, is the smallest genus in the family of prehistoric lobe-finned fish, Tristichopteridae that was believed to have originated in the north and dispersed throughout the course of the Upper Devonian into Gondwana. Tristichopterus currently has only one named species, first described by Egerton in 1861. The Tristichopterus node is thought to have originated during the Givetian part of the Devonian. Tristichopterus was thought by Egerton to be unique for its time period as a fish with ossified vertebral centers, breaking the persistent notochord rule of most Devonian fish but this was later reinspected and shown to be only partial ossification by Dr. R. H. Traquair. Tristichopterus alatus closely resembles Eusthenopteron and this sparked some debate after its discovery as to whether it was a separate taxon.

Guiyu oneiros is one of the earliest articulated bony fish discovered. Fossils of Guiyu have been found in what is now Qujing, Yunnan, China, in late Silurian marine strata, about 425 million years old.

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible, lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lower – and typically more mobile – component of the mouth.

Laccognathus embryi is an extinct species of porolepiform lobe-finned fish recovered from Ellesmere Island, Canada. It existed during the Frasnian age of the Late Devonian epoch.

Ymeria is an extinct genus of early stem tetrapod from the Devonian of Greenland. Of the two other genera of stem tetrapods from Greenland, Acanthostega and Ichthyostega, Ymeria is most closely related to Ichthyostega, though the single known specimen is smaller, the skull about 10 cm in length. A single interclavicle resembles that of Ichthyostega, an indication Ymeria may have resembled this genus in the post-cranial skeleton.

Most bony fishes have two sets of jaws made mainly of bone. The primary oral jaws open and close the mouth, and a second set of pharyngeal jaws are positioned at the back of the throat. The oral jaws are used to capture and manipulate prey by biting and crushing. The pharyngeal jaws, so-called because they are positioned within the pharynx, are used to further process the food and move it from the mouth to the stomach.

The evolution of fish began about 530 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion. It was during this time that the early chordates developed the skull and the vertebral column, leading to the first craniates and vertebrates. The first fish lineages belong to the Agnatha, or jawless fish. Early examples include Haikouichthys. During the late Cambrian, eel-like jawless fish called the conodonts, and small mostly armoured fish known as ostracoderms, first appeared. Most jawless fish are now extinct; but the extant lampreys may approximate ancient pre-jawed fish. Lampreys belong to the Cyclostomata, which includes the extant hagfish, and this group may have split early on from other agnathans.

Qilinyu is a genus of early placoderm from the late Silurian of China. It contains a single species, Qilinyu rostrata, from the Xiaoxiang fauna of the Kuanti Formation. Along with its contemporary Entelognathus, Qilinyu is an unusual placoderm showing some traits more similar to bony fish, such as dermal jaw bones and lobe-like fins. It can be characterized by adaptations for a benthic lifestyle, with the mouth and nostrils on the underside of the head, similar to the unrelated antiarch placoderms. The shape of the skull has been described as "dolphin-like", with a domed cranium and a short projecting rostrum.

Manubrantlia was a genus of lapillopsid from the Early Triassic Panchet Formation of India. This genus is only known from a single holotype left jaw, given the designation ISI A 57. Despite the paucity of remains, the jaw is still identifiable as belonging to a relative of Lapillopsis. For example, all three of its coronoid bones possessed teeth, the articular bone is partially visible in lateral (outer) view, and its postsplenial does not contact the posterior meckelian foramen. However, the jaw also possesses certain unique features which justify the erection of a new genus separate from Lapillopsis. For example, the mandible is twice the size of any jaws referred to other lapillopsids. The most notable unique feature is an enlarged "pump-handle" shaped arcadian process at the back of the jaw. This structure is responsible for the generic name of this genus, as "Manubrantlia" translates from Latin to the English expression "pump-handle". The type and only known species of this genus is Manubrantlia khaki. The specific name refers to the greenish-brown mudstones of the Panchet Formation, with a color that had been described as "khaki" by the first British geologists who studied the formation.

Andersonerpeton is an extinct genus of aïstopod from the Bashkirian of Nova Scotia, Canada. It is known from a single jaw, which shares an unusual combination of features from both other aistopods and from stem-tetrapod tetrapodomorph fish. As a result, Andersonerpeton is significant for supporting a new classification scheme which states that aistopods evolved much earlier than previously expected. The genus contains a single species, A. longidentatum, which was previously believed to have been a species of the microsaur Hylerpeton.