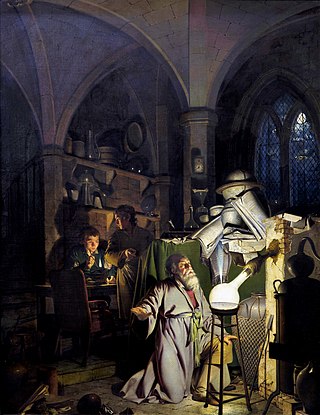

Alchemy is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD.

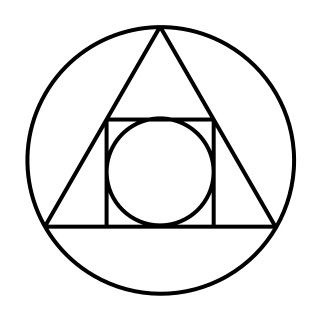

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver. It is also called the elixir of life, useful for rejuvenation and for achieving immortality; for many centuries, it was the most sought-after goal in alchemy. The philosopher's stone was the central symbol of the mystical terminology of alchemy, symbolizing perfection at its finest, enlightenment, and heavenly bliss. Efforts to discover the philosopher's stone were known as the Magnum Opus.

Arthur Dee was a physician and alchemist. He became a physician successively to Tsar Michael I of Russia and to King Charles I of England.

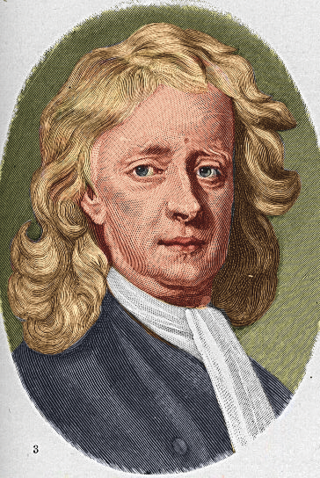

English physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton produced works exploring chronology, and biblical interpretation, and alchemy. Some of this could be considered occult. Newton's scientific work may have been of lesser personal importance to him, as he placed emphasis on rediscovering the wisdom of the ancients. Historical research on Newton's occult studies in relation to his science have also been used to challenge the disenchantment narrative within critical theory.

The elixir of life, also known as elixir of immortality, is a potion that supposedly grants the drinker eternal life and/or eternal youth. This elixir was also said to cure all diseases. Alchemists in various ages and cultures sought the means of formulating the elixir.

Chinese alchemy is an ancient Chinese scientific and technological approach to alchemy, a part of the larger tradition of Taoist body-spirit cultivation developed from the traditional Chinese understanding of medicine and the body. According to original texts such as the Cantong qi, the body is understood as the focus of cosmological processes summarized in the five agents of change, or Wuxing, the observation and cultivation of which leads the practitioner into alignment and harmony with the Tao. Therefore, the traditional view in China is that alchemy focuses mainly on longevity and the purification of one's spirit, mind and body, providing, health, longevity and wisdom, through the practice of Qigong and wuxingheqidao. The consumption and use of various concoctions known as alchemical medicines or elixirs, each of which having different purposes but largely were concerned with immortality.

Projection was the ultimate goal of Western alchemy. Once the philosopher's stone or powder of projection had been created, the process of projection would be used to transmute a lesser substance into a higher form; often lead into gold.

Thomas Vaughan was a Welsh clergyman, philosopher, and alchemist, who wrote in English. He is now remembered for his work in the field of natural magic. He also published under the pseudonym Eugenius Philalethes.

Psychology and Alchemy, volume 12 in The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, is Carl Jung's study of the analogies between alchemy, Christian dogma, and psychological symbolism.

George Starkey (1628–1665) was a Colonial American alchemist, medical practitioner, and writer of numerous commentaries and chemical treatises that were widely circulated in Western Europe and influenced prominent men of science, including Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton. After relocating from New England to London, England, in 1650, Starkey began writing under the pseudonym Eirenaeus Philalethes. Starkey remained in England and continued his career in medicine and alchemy until his death in the Great Plague of London in 1665.

Sir George Ripley was an English Augustinian canon, author, and alchemist.

Diana's Tree, also known as the Philosopher's Tree, was considered a precursor to the philosopher's stone and resembled coral in regards to its structure. It is a dendritic amalgam of crystallized silver, obtained from mercury in a solution of silver nitrate; so-called by the alchemists, among whom "Diana" stood for silver. The arborescence of this amalgam, which even included fruit-like forms on its branches, led pre-modern chemical philosophers to theorize the existence of life in the kingdom of minerals.

The Baopuzi is a literary work written by Ge Hong (葛洪), 283–343, a scholar during the turbulent Jin dynasty. Baopuzi is divided into two main sections, the esoteric Neipian (內篇) "Inner Chapters" and the section intended for the public to understand, Waipian (外篇) "Outer Chapters". The Taoist Inner Chapters discuss topics such as techniques to achieve "hsien" (仙) "immortality; transcendence", Chinese alchemy, elixirs, and demonology. The Confucian Outer Chapters discuss Chinese literature, Legalism, politics, and society.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to alchemy:

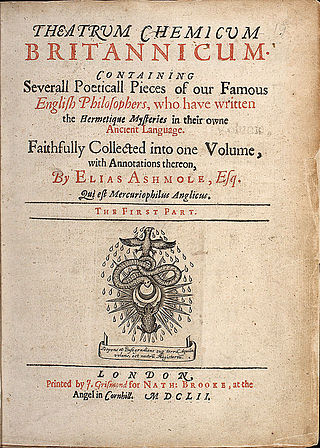

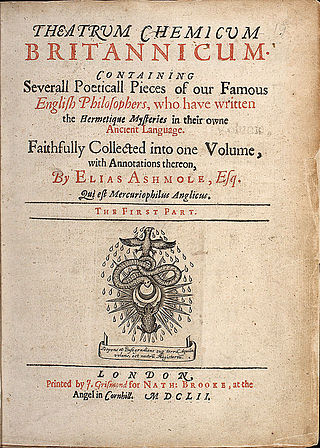

Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum first published in 1652, is an extensively annotated compilation of English alchemical literature selected by Elias Ashmole. The book preserved and made available many works that had previously existed only in privately held manuscripts. It features the alchemical verse of people such as Thomas Norton, George Ripley, Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower, John Lydgate, John Dastin, Abraham Andrews and William Backhouse.

In alchemy, the Magnum Opus or Great Work is a term for the process of working with the prima materia to create the philosopher's stone. It has been used to describe personal and spiritual transmutation in the Hermetic tradition, attached to laboratory processes and chemical color changes, used as a model for the individuation process, and as a device in art and literature. The magnum opus has been carried forward in New Age and neo-Hermetic movements which sometimes attached new symbolism and significance to the processes. The original process philosophy has four stages:

Waidan, translated as 'external alchemy' or 'external elixir', is the early branch of Chinese alchemy that focuses upon compounding elixirs of immortality by heating minerals, metals, and other natural substances in a luted crucible. The later branch of esoteric neidan 'inner alchemy', which borrowed doctrines and vocabulary from exoteric waidan, is based on allegorically producing elixirs within the endocrine or hormonal system of the practitioner's body, through Daoist meditation, diet, and physiological practices. The practice of waidan external alchemy originated in the early Han dynasty, grew in popularity until the Tang (618–907), when neidan began and several emperors died from alchemical elixir poisoning, and gradually declined until the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

The Mirror of Alchimy is a short alchemical manual, known in Latin as Speculum Alchemiae. Translated in 1597, it was only the second alchemical text printed in the English language. Long ascribed to Roger Bacon (1214-1294), the work is more likely the product of an anonymous author who wrote between the thirteenth and the fifteenth centuries.

Anna Maria Zieglerin was a German alchemist who was found guilty of the murder of a courier, attempted poisoning and intent to burglarize. She was burned alive for her crimes.

In Chinese alchemy, elixir poisoning refers to the toxic effects from elixirs of immortality that contained metals and minerals such as mercury and arsenic. The official Twenty-Four Histories record numerous Chinese emperors, nobles, and officials who died from taking elixirs to prolong their lifespans. The first emperor to die from elixir poisoning was likely Qin Shi Huang and the last was the Yongzheng Emperor. Despite common knowledge that immortality potions could be deadly, fangshi and Daoist alchemists continued the elixir-making practice for two millennia.