The Manzano Group is a group of geologic formations in central New Mexico. These have radiometric ages of 1601 to 1662 million years (Ma), corresponding to the late Statherian period of the Paleoproterozoic.

The Mazatzal orogeny was an orogenic event in what is now the Southwestern United States from 1650 to 1600 Mya in the Statherian Period of the Paleoproterozoic. Preserved in the rocks of New Mexico and Arizona, it is interpreted as the collision of the 1700-1600 Mya age Mazatzal island arc terrane with the proto-North American continent. This was the second in a series of orogenies within a long-lived convergent boundary along southern Laurentia that ended with the ca. 1200–1000 Mya Grenville orogeny during the final assembly of the supercontinent Rodinia, which ended an 800-million-year episode of convergent boundary tectonism.

The Yavapai orogeny was an orogenic (mountain-building) event in what is now the Southwestern United States that occurred between 1710 and 1680 million years ago (Mya), in the Statherian Period of the Paleoproterozoic. Recorded in the rocks of New Mexico and Arizona, it is interpreted as the collision of the 1800-1700 Mya age Yavapai island arc terrane with the proto-North American continent. This was the first in a series of orogenies within a long-lived convergent boundary along southern Laurentia that ended with the ca. 1200–1000 Mya Grenville orogeny during the final assembly of the supercontinent Rodinia, which ended an 800-million-year episode of convergent boundary tectonism.

The Picuris orogeny was an orogenic event in what is now the Southwestern United States from 1.43 to 1.3 billion years ago in the Calymmian Period of the Mesoproterozoic. The event is named for the Picuris Mountains in northern New Mexico and interpreted either as the suturing of the Granite-Rhyolite crustal province to the southern margin of the proto-North American continent Laurentia or as the final suturing of the Mazatzal crustal province onto Laurentia. According to the former hypothesis, this was the second in a series of orogenies within a long-lived convergent boundary along southern Laurentia that ended with the ca. 1200–1000 Mya Grenville orogeny during the final assembly of the supercontinent Rodinia, which ended an 800-million-year episode of convergent boundary tectonism.

The Moppin Complex is a Precambrian geologic complex found in the Tusas Mountains of northern New Mexico. It has not been directly dated, but is thought to be Statherian based on a minimum age of 1.755 Gya from radiometric dating of magmatic intrusions.

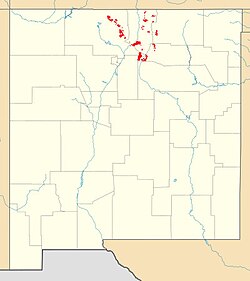

The Vadito Group is a group of geologic formations that crops out in most of the Precambrian-cored uplifts of northern New Mexico. Detrital zircon geochronology and radiometric dating give a consistent age of 1700 Mya for the group, corresponding to the Statherian period.

The Big Rock Formation is a formation that crops out in the Tusas Mountains of northern New Mexico. Detrital zircon geochronology gives a maximum age for the formation of 1665 Mya, corresponding to the Statherian period.

The Burned Mountain Formation is a geologic formation that crops out in the Tusas Mountains of northern New Mexico. It has a U-Pb radiometric age of 1700 Mya, corresponding to the Statherian period.

The Glenwoody Formation is a geological formation that is exposed in the cliffs southeast of the Rio Grande Gorge near the town of Pilar and in a few other locations in the Picuris Mountains. Its minimum age from detrital zircon geochronology is 1.693 Mya, corresponding to the Statherian period.

The Hondo Group is a group of geologic formations that crops out in most of the Precambrian-cored uplifts of northern New Mexico. Detrital zircon geochronology gives a maximum age for the lower Hondo Group of 1765 to 1704 million years (Mya), corresponding to the Statherian period.

The Rinconada Formation is a geologic formation that crops out in the Picuris Mountains of northern New Mexico. Detrital zircon geochronology establishes a maximum age for the Rinconada Formation of about 1723 Mya, placing it in the Statherian period of the Precambrian.

The Pilar Formation is a geologic formation that crops out in the Picuris Mountains of northern New Mexico. It has a radiometric age of 1488 ± 6 million years, corresponding to the Calymmian period.

The Piedra Lumbre Formation is a geologic formation that crops out in the Picuris Mountains of northern New Mexico. Detrital zircon geochronology yields a maximum age of 1475 million years, corresponding to the Calymmian period.

The Marquenas Formation is a geological formation that crops out in the Picuris Mountains of northern New Mexico. Detrital zircon geochronology gives it a maximum age of 1435 million years, corresponding to the Calymmian period.

The Joaquin quartz monzonite is a Mesoproterozoic pluton in northern New Mexico. Radiometric dating gives it an age of 1460 million years, corresponding to the Calymmian period.

The Uncompahgre Formation is a geologic formation in Colorado. Its radiometric age is between 1707 and 1704 Ma, corresponding to the Statherian period.

The Trampas Group is a group of geologic formations that crops out in the Picuris Mountains of northern New Mexico. Detrital zircon geochronology yields a maximum age of 1475 million years, corresponding to the Calymmian period.

The White Ridge Quartzite is a geologic formation in central New Mexico. It has a maximum age of 1650 million years (Ma), corresponding to the Statherian period.

The Abajo Formation is a geologic formation in the Los Pinos Mountains of central New Mexico. It was deposited about 1660 million years (Ma) ago, corresponding to the Statherian period.

The Mazatzal Group is a group of geologic formations that crops out in portions of central Arizona, US. Detrital zircon geochronology establishes a maximum age for the formation of 1660 to 1630 million years (Mya), in the Statherian period of the Precambrian. The group gives its name to the Mazatzal orogeny, a mountain-building event that took place between 1695 and 1630 Mya.