Magnetohydrodynamics is the study of the magnetic properties and behaviour of electrically conducting fluids. Examples of such magnetofluids include plasmas, liquid metals, salt water, and electrolytes. The word "magnetohydrodynamics" is derived from magneto- meaning magnetic field, hydro- meaning water, and dynamics meaning movement. The field of MHD was initiated by Hannes Alfvén, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1970.

Geophysics is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term geophysics sometimes refers only to the geological applications: Earth's shape; its gravitational and magnetic fields; its internal structure and composition; its dynamics and their surface expression in plate tectonics, the generation of magmas, volcanism and rock formation. However, modern geophysics organizations use a broader definition that includes the water cycle including snow and ice; fluid dynamics of the oceans and the atmosphere; electricity and magnetism in the ionosphere and magnetosphere and solar-terrestrial relations; and analogous problems associated with the Moon and other planets.

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from the Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic field is generated by electric currents due to the motion of convection currents of molten iron in the Earth's outer core: these convection currents are caused by heat escaping from the core, a natural process called a geodynamo. The magnitude of the Earth's magnetic field at its surface ranges from 25 to 65 microteslas. As an approximation, it is represented by a field of a magnetic dipole currently tilted at an angle of about 11 degrees with respect to Earth's rotational axis, as if there were a bar magnet placed at that angle at the center of the Earth. The North geomagnetic pole, currently located near Greenland in the northern hemisphere, is actually the south pole of the Earth's magnetic field, and conversely.

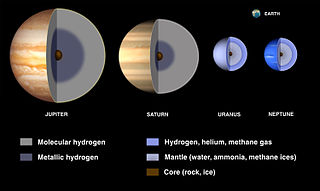

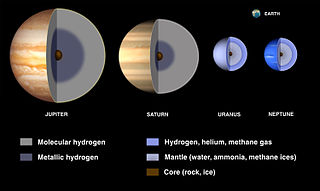

In physics, the dynamo theory proposes a mechanism by which a celestial body such as Earth or a star generates a magnetic field. The dynamo theory describes the process through which a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid can maintain a magnetic field over astronomical time scales. A dynamo is thought to be the source of the Earth's magnetic field and the magnetic fields of Mercury and the Jovian planets.

A ferrofluid is a liquid that becomes strongly magnetized in the presence of a magnetic field. A grinding process for ferrofluid was invented in 1963 by NASA's Steve Papell as a liquid rocket fuel that could be drawn toward a pump inlet in a weightless environment by applying a magnetic field. The name ferrofluid was introduced, the process improved, more highly magnetic liquids synthesized, additional carrier liquids discovered, and the physical chemistry elucidated by R. E. Rosensweig and colleagues; in addition Rosensweig evolved a new branch of fluid mechanics termed ferrohydrodynamics.

The planetary core consists of the innermost layer(s) of a planet. Cores of specific planets may be entirely solid or entirely liquid, or may be a mixture of solid and liquid layers as is the case in the Earth. In the Solar System, core size can range from about 20% (Moon) to 85% of a planet's radius (Mercury).

A P-wave is one of the two main types of elastic body waves, called seismic waves in seismology. P-waves travel faster than other seismic waves and hence are the first signal from an earthquake to arrive at any affected location or at a seismograph. P-waves may be transmitted through gases, liquids, or solids.

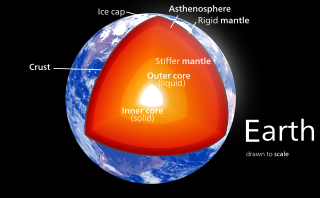

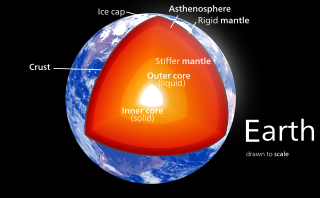

The internal structure of the Earth is layered in spherical shells: an outer silicate solid crust, a highly viscous asthenosphere and mantle, a liquid outer core that is much less viscous than the mantle, and a solid inner core. Scientific understanding of the internal structure of the Earth is based on observations of topography and bathymetry, observations of rock in outcrop, samples brought to the surface from greater depths by volcanoes or volcanic activity, analysis of the seismic waves that pass through the Earth, measurements of the gravitational and magnetic fields of the Earth, and experiments with crystalline solids at pressures and temperatures characteristic of the Earth's deep interior.

The core–mantle boundary of the Earth lies between the planet's silicate mantle and its liquid iron-nickel outer core. This boundary is located at approximately 2891 km (1796 mi) depth beneath the Earth's surface. The boundary is observed via the discontinuity in seismic wave velocities at that depth due to the differences between the acoustic impedances of the solid mantle and the molten outer core. P-wave velocities are much slower in the outer core than in the deep mantle while S-waves do not exist at all in the liquid portion of the core. Recent evidence suggests a distinct boundary layer directly above the CMB possibly made of a novel phase of the basic perovskite mineralogy of the deep mantle named post-perovskite. Seismic tomography studies have shown significant irregularities within the boundary zone and appear to be dominated by the African and Pacific large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs).

A geomagnetic reversal is a change in a planet's magnetic field such that the positions of magnetic north and magnetic south are interchanged. The Earth's field has alternated between periods of normal polarity, in which the predominant direction of the field was the same as the present direction, and reverse polarity, in which it was the opposite. These periods are called chrons.

Earth's inner core is the innermost geologic layer of the Earth. It is primarily a solid ball with a radius of about 1,220 kilometres, which is about 20% of the Earth's radius and 70% of the Moon's radius.

Having a mean density of 3,346.4 kg/m³, the Moon is a differentiated body, being composed of a geochemically distinct crust, mantle, and planetary core. This structure is believed to have resulted from the fractional crystallization of a magma ocean shortly after its formation about 4.5 billion years ago. The energy required to melt the outer portion of the Moon is commonly attributed to a giant impact event that is postulated to have formed the Earth-Moon system, and the subsequent reaccretion of material in Earth orbit. Crystallization of this magma ocean would have given rise to a mafic mantle and a plagioclase-rich crust.

A coreless planet is a theoretical type of terrestrial planet that has no metallic core, i.e. the planet is effectively a giant rocky mantle.

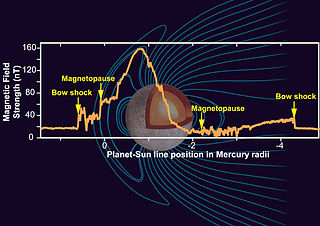

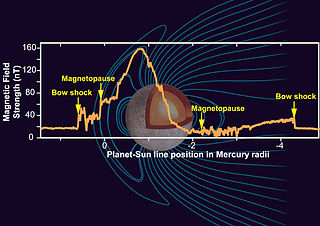

Mercury's magnetic field is approximately a magnetic dipole apparently global, on planet Mercury. Data from Mariner 10 led to its discovery in 1974; the spacecraft measured the field's strength as 1.1% that of Earth's magnetic field. The origin of the magnetic field can be explained by dynamo theory. The magnetic field is strong enough near the bow shock to slow the solar wind, which induces a magnetosphere.

Crustal recycling is a tectonic process by which surface material from the lithosphere is recycled into the mantle by subduction erosion or delamination. The subducting slabs carry volatile compounds and water into the mantle, as well as crustal material with an isotopic signature different from that of primitive mantle. Identification of this crustal signature in mantle-derived rocks is proof of crustal recycling.

The thermal history of the Earth involves the study of the cooling history of Earth's interior. It is a sub-field of geophysics. The study of the thermal evolution of Earth's interior is uncertain and controversial in all aspects, from the interpretation of petrologic observations used to infer the temperature of the interior, to the fluid dynamics responsible for heat loss, to material properties that determine the efficiency of heat transport.

Ultra low velocity zones (ULVZs) are patches on the core-mantle boundary that have extremely low seismic velocities. The zones are mapped to be hundreds of kilometers in diameter and tens of kilometers thick. Their shear wave velocities can be up to 30% lower than surrounding material. The composition and origin of the zones remain uncertain. The zones appear to correlate with edges of the African and Pacific Large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs) as well as the location of hotspots.

Inner core super-rotation is the theory that the inner core of Earth is rotating more quickly than its outer core. The theory is based on discrepancies in the time that p-waves take to travel through the inner and outer core. The theory was initially greeted with skepticism but more recent studies suggest there may be a semi-solid layer at the boundary between the inner and outer cores.