Pteranodon ; from Ancient Greek πτερόν and ἀνόδων is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with P. longiceps having a wingspan of over 6 m (20 ft). They lived during the late Cretaceous geological period of North America in present-day Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, South Dakota and Alabama. More fossil specimens of Pteranodon have been found than any other pterosaur, with about 1,200 specimens known to science, many of them well preserved with nearly complete skulls and articulated skeletons. It was an important part of the animal community in the Western Interior Seaway.

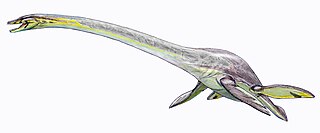

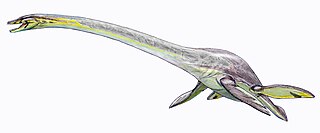

Plesiosauroidea is an extinct clade of carnivorous marine reptiles. They have the snake-like longest neck to body ratio of any reptile. Plesiosauroids are known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. After their discovery, some plesiosauroids were said to have resembled "a snake threaded through the shell of a turtle", although they had no shell.

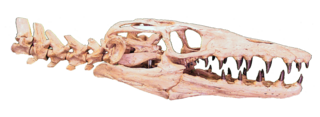

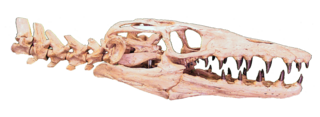

Tylosaurus is a genus of mosasaur, a large, predatory marine reptile closely related to modern monitor lizards and to snakes, from the Late Cretaceous.

Selmasaurus is an extinct genus of marine lizard belonging to the mosasaur family. It is classified as part of the Plioplatecarpinae subfamily alongside genera like Angolasaurus and Platecarpus. Two species are known, S. russelli and S. johnsoni; both are exclusively known from Santonian deposits in the United States.

The Tylosaurinae are a subfamily of mosasaurs, a diverse group of Late Cretaceous marine squamates. Members of the subfamily are informally and collectively known as "tylosaurines" and have been recovered from every continent except for South America. The subfamily includes the genera Tylosaurus, Taniwhasaurus, and Kaikaifilu, although some scientists argue that only Tylosaurus and Taniwhasaurus should be included.

Protosphyraena is a fossil genus of swordfish-like marine fish, that thrived worldwide during the Upper Cretaceous Period (Coniacian-Maastrichtian). Though fossil remains of this taxon have been found in both Europe and Asia, it is perhaps best known from the Smoky Hill Member of the Niobrara Chalk Formation of Kansas. Protosphyraena was a large fish, averaging 2–3 metres in length. Protosphyraena shared the Cretaceous oceans with aquatic reptiles, such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, as well as with many other species of extinct predatory fish. The name Protosphyraena is a combination of the Greek word protos ("early") plus Sphyraena, the genus name for barracuda, as paleontologists initially mistook Protosphyraena for an ancestral barracuda. Recent research shows that the genus Protosphyraena is not at all related to the true swordfish-family Xiphiidae, but belongs to the extinct family Pachycormidae.

Nyctosaurus is a genus of nyctosaurid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of what is now the Niobrara Formation of the mid-western United States, which, during the time Nyctosaurus was alive, was covered in an extensive shallow sea. Some remains belonging to a possible Nyctosaurus species called N.lamegoi have been found in Brazil, making Nyctosaurus more diverse. The genus Nyctosaurus has had numerous species referred to it, though how many of these may actually be valid requires further study. At least one species possessed an extraordinarily large antler-like cranial crest.

Dolichorhynchops is an extinct genus of polycotylid plesiosaur from the Late Cretaceous of North America, containing the species D. osborni and D. herschelensis, with two previous species having been assigned to new genera. Dolichorhynchops was a prehistoric marine reptile. Its Greek generic name means "long-nosed face". While typically measuring about 3 metres (9.8 ft) in length, the largest specimen of D. osborni is estimated to have a total body length more than approximately 4.29 metres (14.1 ft).

The Bearpaw Formation, also called the Bearpaw Shale, is a geologic formation of Late Cretaceous (Campanian) age. It outcrops in the U.S. state of Montana, as well as the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, and was named for the Bear Paw Mountains in Montana. It includes a wide range of marine fossils, as well as the remains of a few dinosaurs. It is known for its fossil ammonites, some of which are mined in Alberta to produce the organic gemstone ammolite.

Styxosaurus is a genus of plesiosaur of the family Elasmosauridae. Styxosaurus lived during the Campanian age of the Cretaceous period. Three species are known: S. snowii, S. browni, and S. rezaci.

The Pierre Shale is a geologic formation or series in the Upper Cretaceous which occurs east of the Rocky Mountains in the Great Plains, from Pembina Valley in Canada to New Mexico.

The Mooreville Chalk is a geological formation in North America, within the U.S. states of Alabama and Mississippi, which were part of the subcontinent of Appalachia. The strata date back to the early Santonian to the early Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous. The chalk was formed by pelagic sediments deposited along the eastern edge of the Mississippi embayment. It is a unit of the Selma Group and consists of the upper Arcola Limestone Member and an unnamed lower member. Dinosaur, mosasaur, and primitive bird remains are among the fossils that have been recovered from the Mooreville Chalk Formation.

The Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk formation is a Cretaceous conservation Lagerstätte, or fossil rich geological formation, known primarily for its exceptionally well-preserved marine reptiles. Named for the Smoky Hill River, the Smoky Hill Chalk Member is the uppermost of the two structural units of the Niobrara Chalk. It is underlain by the Fort Hays Limestone Member; and the Pierre Shale overlies the Smoky Hill Chalk. The Smoky Hill Chalk outcrops in parts of northwest Kansas, its most famous localities for fossils, and in southeastern Nebraska. Large well-known fossils excavated from the Smoky Hill Chalk include marine reptiles such as plesiosaurs, large bony fish such as Xiphactinus, mosasaurs, flying reptiles or pterosaurs, flightless marine birds such as Hesperornis, and turtles. Many of the most well-known specimens of the marine reptiles were collected by dinosaur hunter Charles H. Sternberg and his son George. The son collected a unique fossil of the giant bony fish Xiphactinus audax with the skeleton of another bony fish, Gillicus arcuatus inside the larger one. Another excellent skeleton of Xiphactinus audax was collected by Edward Drinker Cope during the late nineteenth century heyday of American paleontology and its Bone Wars.

Angolasaurus is an extinct genus of mosasaur. Definite remains from this genus have been recovered from the Turonian and Coniacian of Angola, and possibly the Coniacian of the United States, the Turonian of Brazil, and the Maastrichtian of Niger. While at one point considered a species of Platecarpus, recent phylogenetic analyses have placed it between the (then) plioplatecarpines Ectenosaurus and Selmasaurus, maintaining a basal position within the plioplatecarpinae.

The Carlile Shale is a Turonian age Upper/Late Cretaceous series shale geologic formation in the central-western United States, including in the Great Plains region of Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

Paleontology in New Jersey refers to paleontological research in the U.S. state of New Jersey. The state is especially rich in marine deposits.

Paleontology in Iowa refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Iowa. The paleozoic fossil record of Iowa spans from the Cambrian to Mississippian. During the early Paleozoic Iowa was covered by a shallow sea that would later be home to creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, cephalopods, corals, fishes, and trilobites. Later in the Paleozoic, this sea left the state, but a new one covered Iowa during the early Mesozoic. As this sea began to withdraw a new subtropical coastal plain environment which was home to duck-billed dinosaurs spread across the state. Later this plain was submerged by the rise of the Western Interior Seaway, where plesiosaurs lived. The early Cenozoic is missing from the local rock record, but during the Ice Age evidence indicates that glaciers entered the state, which was home to mammoths and mastodons.

Paleontology in Nebraska refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Nebraska. Nebraska is world-famous as a source of fossils. During the early Paleozoic, Nebraska was covered by a shallow sea that was probably home to creatures like brachiopods, corals, and trilobites. During the Carboniferous, a swampy system of river deltas expanded westward across the state. During the Permian period, the state continued to be mostly dry land. The Triassic and Jurassic are missing from the local rock record, but evidence suggests that during the Cretaceous the state was covered by the Western Interior Seaway, where ammonites, fish, sea turtles, and plesiosaurs swam. The coasts of this sea were home to flowers and dinosaurs. During the early Cenozoic, the sea withdrew and the state was home to mammals like camels and rhinoceros. Ice Age Nebraska was subject to glacial activity and home to creatures like the giant bear Arctodus, horses, mammoths, mastodon, shovel-tusked proboscideans, and Saber-toothed cats. Local Native Americans devised mythical explanations for fossils like attributing them to water monsters killed by their enemies, the thunderbirds. After formally trained scientists began investigating local fossils, major finds like the Agate Springs mammal bone beds occurred. The Pleistocene mammoths Mammuthus primigenius, Mammuthus columbi, and Mammuthus imperator are the Nebraska state fossils.

Paleontology in Kansas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Kansas. Kansas has been the source of some of the most spectacular fossil discoveries in US history. The fossil record of Kansas spans from the Cambrian to the Pleistocene. From the Cambrian to the Devonian, Kansas was covered by a shallow sea. During the ensuing Carboniferous the local sea level began to rise and fall. When sea levels were low the state was home to richly vegetated deltaic swamps where early amphibians and reptiles lived. Seas expanded across most of the state again during the Permian, but on land the state was home to thousands of different insect species. The popular pterosaur Pteranodon is best known from this state. During the early part of the Cenozoic era Kansas became a savannah environment. Later, during the Ice Age, glaciers briefly entered the state, which was home to camels, mammoths, mastodons, and saber-teeth. Local fossils may have inspired Native Americans to regard some local hills as the homes of sacred spirit animals. Major scientific discoveries in Kansas included the pterosaur Pteranodon and a fossil of the fish Xiphactinus that died in the act of swallowing another fish.

This timeline of mosasaur research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation, and taxonomic revisions of mosasaurs, a group of giant marine lizards that lived during the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Although mosasaurs went extinct millions of years before humans evolved, humans have coexisted with mosasaur fossils for millennia. Before the development of paleontology as a formal science, these remains would have been interpreted through a mythological lens. Myths about warfare between serpentine water monsters and aerial thunderbirds told by the Native Americans of the modern western United States may have been influenced by observations of mosasaur fossils and their co-occurrence with creatures like Pteranodon and Hesperornis.