Pteranodon ; from Ancient Greek πτερόν and ἀνόδων is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with P. longiceps having a wingspan of over 6 m (20 ft). They lived during the late Cretaceous geological period of North America in present-day Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, South Dakota and Alabama. More fossil specimens of Pteranodon have been found than any other pterosaur, with about 1,200 specimens known to science, many of them well preserved with nearly complete skulls and articulated skeletons. It was an important part of the animal community in the Western Interior Seaway.

Cretoxyrhina is an extinct genus of large mackerel shark that lived about 107 to 73 million years ago during the late Albian to late Campanian of the Late Cretaceous. The type species, C. mantelli, is more commonly referred to as the Ginsu shark, first popularized in reference to the Ginsu knife, as its theoretical feeding mechanism is often compared with the "slicing and dicing" when one uses the knife. Cretoxyrhina is traditionally classified as the likely sole member of the family Cretoxyrhinidae but other taxonomic placements have been proposed, such as within the Alopiidae and Lamnidae.

Hesperornithes is an extinct and highly specialized group of aquatic avialans closely related to the ancestors of modern birds. They inhabited both marine and freshwater habitats in the Northern Hemisphere, and include genera such as Hesperornis, Parahesperornis, Baptornis, Enaliornis, and Potamornis, all strong-swimming, predatory divers. Many of the species most specialized for swimming were completely flightless. The largest known hesperornithean, Canadaga arctica, may have reached a maximum adult length of 2.2 metres (7.2 ft).

Hesperornis is a genus of cormorant-like Ornithuran that spanned throughout the Campanian age, and possibly even up to the early Maastrichtian age, of the Late Cretaceous period. One of the lesser-known discoveries of the paleontologist O. C. Marsh in the late 19th century Bone Wars, it was an early find in the history of avian paleontology. Locations for Hesperornis fossils include the Late Cretaceous marine limestones from Kansas and the marine shales from Canada. Nine species are recognised, eight of which have been recovered from rocks in North America and one from Russia.

Tylosaurus is a genus of russellosaurine mosasaur that lived about 92 to 66 million years ago during the Turonian to Maastrichtian stages of the Late Cretaceous. Its fossils have been found primarily around North Atlantic Ocean including in North America, Europe, and Africa. The earliest discoveries were possibly made by Native American tribes in the Great Plains, whose creation myths spoke of giant serpentine water monsters turned to stone in ancient times. Paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope first scientifically described fossils of the genus from Kansas in 1869, but the name Tylosaurus was coined by Cope's rival Othniel Charles Marsh.

Odontornithes is an obsolete and disused taxonomic term proposed by Othniel Charles Marsh for birds possessing teeth, notably the genera Hesperornis and Ichthyornis from the Cretaceous deposits of Kansas.

The UW–Madison Geology Museum (UWGM) is a geology and paleontology museum housed in Weeks Hall, in the southwest part of the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus. The museum's main undertakings are exhibits, outreach to the public, and research. It has the second highest attendance of any museum at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, exceeded only by the Chazen Museum of Art. The museum charges no admission.

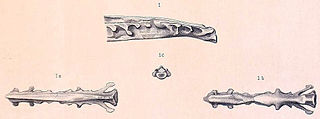

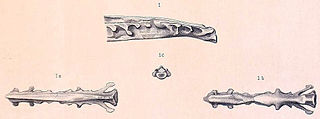

Protosphyraena is a fossil genus of swordfish-like marine fish, that thrived worldwide during the Upper Cretaceous Period (Coniacian-Maastrichtian). Though fossil remains of this taxon have been found in both Europe and Asia, it is perhaps best known from the Smoky Hill Member of the Niobrara Chalk Formation of Kansas. Protosphyraena was a large fish, averaging 2–3 metres in length. Protosphyraena shared the Cretaceous oceans with aquatic reptiles, such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, as well as with many other species of extinct predatory fish. The name Protosphyraena is a combination of the Greek word protos ("early") plus Sphyraena, the genus name for barracuda, as paleontologists initially mistook Protosphyraena for an ancestral barracuda. Recent research shows that the genus Protosphyraena is not at all related to the true swordfish-family Xiphiidae, but belongs to the extinct family Pachycormidae.

Ichthyornithes is an extinct group of toothed avialan dinosaurs very closely related to the common ancestor of all modern birds. They are known from fossil remains found throughout the late Cretaceous period of North America, though only two genera, Ichthyornis and Janavis, are represented by complete enough fossils to have been named. Ichthyornitheans became extinct at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, along with enantiornitheans, all other non-avian dinosaurs, and many other animal and plant groups.

Baptornis is a genus of flightless, aquatic birds from the Late Cretaceous, some 87-80 million years ago. The fossils of Baptornis advenus, the type species, were discovered in Kansas, which at its time was mostly covered by the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow shelf sea. It is now known to have also occurred in today's Sweden, where the Turgai Strait joined the ancient North Sea; possibly, it occurred in the entire Holarctic.

Polarornis is a genus of prehistoric bird, possibly an anserimorph. It contains a single species Polarornis gregorii, known from incomplete remains of one individual found on Seymour Island, Antarctica, in rocks which are dated to the Late Cretaceous.

Benjamin Franklin Mudge was an American lawyer, geologist and teacher. Briefly the mayor of Lynn, Massachusetts, he later moved to Kansas where he was appointed the first State Geologist. He led the first geological survey of the state in 1864, and published the first book on the geology of Kansas. He lectured extensively, and was department chair at the Kansas State Agricultural College.

Apatornis is a genus of ornithuran dinosaurs endemic to North America during the late Cretaceous. It currently contains a single species, Apatornis celer, which lived around the Santonian-Campanian boundary, dated to about 83.5 million years ago. The remains of this species were found in the Smoky Hill Chalk of the Niobrara Formation in Kansas, United States. It is known from a single fossil specimen: a synsacrum, the fused series of vertebrae over the hips.

Parahesperornis is a genus of prehistoric flightless birds from the Late Cretaceous. Its range in space and time may have been extensive, but its remains are rather few and far between, at least compared with its contemporary relatives in Hesperornis. Remains are known from central North America, namely the former shallows of the Western Interior Seaway in Kansas. Found only in the upper Niobrara Chalk, these are from around the Coniacian-Santonian boundary, 85–82 million years ago (mya).

The Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk formation is a Cretaceous conservation Lagerstätte, or fossil rich geological formation, known primarily for its exceptionally well-preserved marine reptiles. Named for the Smoky Hill River, the Smoky Hill Chalk Member is the uppermost of the two structural units of the Niobrara Chalk. It is underlain by the Fort Hays Limestone Member and overlain by the Pierre Shale. The Smoky Hill Chalk outcrops in parts of northwest Kansas, its most famous localities for fossils, and in southeastern Nebraska. Large well-known fossils excavated from the Smoky Hill Chalk include marine reptiles such as plesiosaurs, large bony fish such as Xiphactinus, mosasaurs, flying reptiles or pterosaurs, flightless marine birds such as Hesperornis, and turtles. Many of the most well-known specimens of the marine reptiles were collected by dinosaur hunter Charles H. Sternberg and his son George. The son collected a unique fossil of the giant bony fish Xiphactinus audax with the skeleton of another bony fish, Gillicus arcuatus inside the larger one. Another excellent skeleton of Xiphactinus audax was collected by Edward Drinker Cope during the late nineteenth century heyday of American paleontology and its Bone Wars.

During the time of the deposition of the Niobrara Chalk, much life inhabited the seas of the Western Interior Seaway. By this time in the Late Cretaceous many new lifeforms appeared such as mosasaurs, which were to be some of the last of the aquatic lifeforms to evolve before the end of the Mesozoic. Life of the Niobrara Chalk is comparable to that of the Dakota Formation, although the Dakota Formation, which was deposited during the Cenomanian, predates the chalk by about 10 million years.

Iaceornis is a genus of marine ornithuran dinosaurs closely related to modern birds. It was endemic to North America during the Late Cretaceous, living about 83.5 million years ago. It is known from a single fossil specimen found in Gove County, Kansas (USA), and consisting of a partial skeleton lacking a skull.

Pteranodontoidea is an extinct clade of ornithocheiroid pterosaurs from the Early to Late Cretaceous of Asia, Africa, Europe, North America and South America. It was named by Alexander Wilhelm Armin Kellner in 1996. In 2003, Kellner defined the clade as a node-based taxon consisting of the last common ancestor of Anhanguera, Pteranodon and all its descendants. The clade Ornithocheiroidea is sometimes considered to be the senior synonym of Pteranodontoidea, however it depends on its definition. Brian Andres in his analyses, converts Ornithocheiroidea using the definition of Kellner (2003) to avoid this synonymy.

This timeline of mosasaur research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation, and taxonomic revisions of mosasaurs, a group of giant marine lizards that lived during the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Although mosasaurs went extinct millions of years before humans evolved, humans have coexisted with mosasaur fossils for millennia. Before the development of paleontology as a formal science, these remains would have been interpreted through a mythological lens. Myths about warfare between serpentine water monsters and aerial thunderbirds told by the Native Americans of the modern western United States may have been influenced by observations of mosasaur fossils and their co-occurrence with creatures like Pteranodon and Hesperornis.

Tingmiatornis is a genus of flighted and possibly diving ornithurine dinosaur from the High Arctic of Canada. The genus contains a single species, T. arctica, described in 2016, which lived during the Turonian epoch of the Cretaceous.