Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, he spearheaded the Muslim military effort against the Crusader states in the Levant. At the height of his power, the Ayyubid realm spanned Egypt, Syria, Upper Mesopotamia, the Hejaz, Yemen, and Nubia.

The Ayyubid dynasty, also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin had originally served the Zengid ruler Nur ad-Din, leading Nur ad-Din's army in battle against the Crusaders in Fatimid Egypt, where he was made Vizier. Following Nur ad-Din's death, Saladin was proclaimed as the first Sultan of Egypt by the Abbasid Caliphate, and rapidly expanded the new sultanate beyond the frontiers of Egypt to encompass most of the Levant, in addition to Hijaz, Yemen, northern Nubia, Tarabulus, Cyrenaica, southern Anatolia, and northern Iraq, the homeland of his Kurdish family. By virtue of his sultanate including Hijaz, the location of the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina, he was the first ruler to be hailed as the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, a title that would be held by all subsequent sultans of Egypt until the Ottoman conquest of 1517. Saladin's military campaigns in the first decade of his rule, aimed at uniting the various Arab and Muslim states in the region against the Crusaders, set the general borders and sphere of influence of the sultanate of Egypt for the almost three and a half centuries of its existence. Most of the Crusader states, including the Kingdom of Jerusalem, fell to Saladin after his victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. However, the Crusaders reconquered the coast of Palestine in the 1190s.

The Zengid or Zangid dynasty was an Atabegate of the Seljuk Empire created in 1127. It formed a Turkoman dynasty of Sunni Muslim faith, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia, and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to Hamadan and from Yemen to Sivas. Imad ad-Din Zengi was the first ruler of the dynasty.

Waddesdon Manor is a country house in the village of Waddesdon, in Buckinghamshire, England. Owned by the National Trust and managed by the Rothschild Foundation, it is one of the National Trust's most visited properties, with over 463,000 visitors in 2019.

In art history, the French term objet d’art describes an ornamental work of art, and the term objets d’art describes a range of works of art, usually small and three-dimensional, made of high-quality materials, and a finely-rendered finish that emphasises the aesthetics of the artefact. Artists create and produce objets d’art in the fields of the decorative arts and metalwork, porcelain and vitreous enamel; figurines, plaquettes, and engraved gems; ivory carvings and semi-precious hardstone carvings; tapestries, antiques, and antiquities; and books with fine bookbinding.

The Artuqid dynasty was established in 1102 as a Beylik (Principality) of the Seljuk Empire. It formed a Turkoman dynasty rooted in the Oghuz Döğer tribe, and followed the Sunni Muslim faith. It ruled in eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Iraq in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. The Artuqid dynasty took its name from its founder, Artuk Bey, who was of the Döger branch of the Oghuz Turks and ruled one of the Turkmen beyliks of the Seljuk Empire. Artuk's sons and descendants ruled the three branches in the region: Sökmen's descendants ruled the region around Hasankeyf between 1102 and 1231; Ilghazi's branch ruled from Mardin and Mayyafariqin between 1106 and 1186 and Aleppo from 1117–1128; and the Harput line starting in 1112 under the Sökmen branch, and was independent between 1185 and 1233.

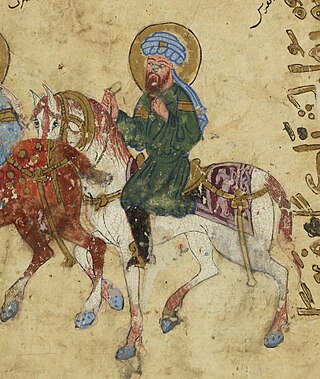

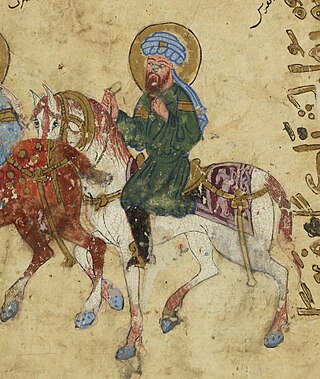

Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti was a 13th-century Iraqi-Arab painter and calligrapher, noted for being the scribe and illustrator of al-Hariri's Maqamat dated 1237 CE.

The "Luck of Edenhall" is an enamelled glass beaker that was made in Syria or Egypt in the middle of the 14th century, elegantly decorated with arabesques in blue, green, red and white enamel with gilding. It is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and is 15.8 cm high and 11.1 cm wide at the brim. It had reached Europe by the 15th century, when it was provided with a decorated stiff case in boiled leather with a lid, which includes the Christian IHS; this no doubt helped it to survive over the centuries.

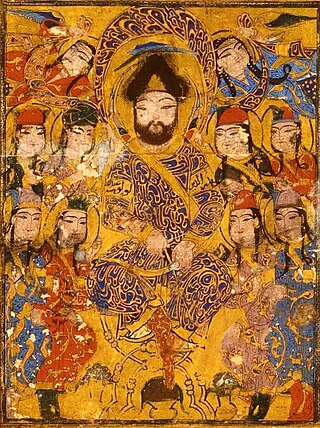

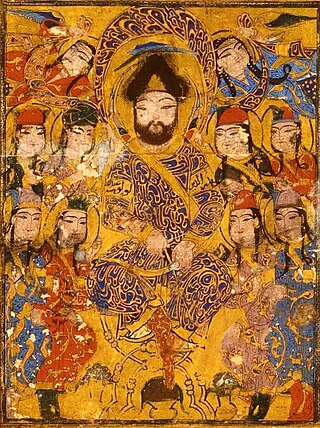

Badr al-Din Lu'lu' was successor to the Zengid emirs of Mosul, where he governed in variety of capacities from 1234 to 1259 following the death of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud. He was the founder of the short-lived Luluid dynasty. Originally a slave of the Zengid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, he was the first Middle-Eastern mamluk to transcend servitude and become an emir in his own right, founding the dynasty of the Lu'lu'id emirs (1234-1262), and anticipating the rise of the Bahri Mamluks of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt by twenty years. He preserved control of al-Jazira through a series of tactical submissions to larger neighboring powers, at various times recognizing Ayyubid, Rûmi Seljuq, and Mongol overlords. His surrender to the Mongols after 1243 temporarily spared Mosul the destruction experienced by other settlements in Mesopotamia.

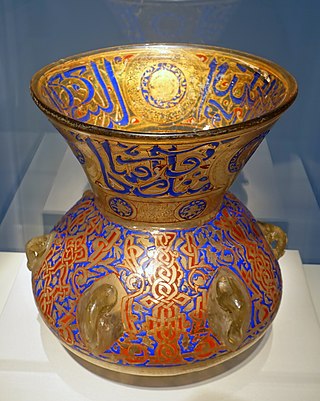

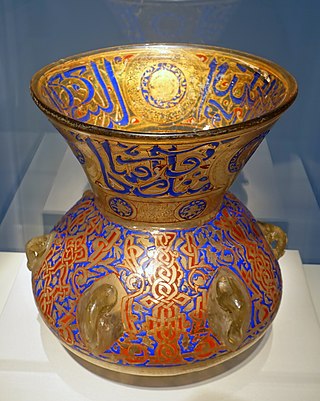

Islamic glass built on pre-Islamic cultures in the Middle East, especially ancient Egyptian, Persian and Roman glass, and developed distinct styles, characterized by the introduction of new techniques and the reinterpreting of old traditions. It came under European influence by the end of the Middle Ages.

The Holy Thorn Reliquary was probably created in the 1390s in Paris for John, Duke of Berry, to house a relic of the Crown of Thorns. The reliquary was bequeathed to the British Museum in 1898 by Ferdinand de Rothschild as part of the Waddesdon Bequest. It is one of a small number of major goldsmiths' works or joyaux that survive from the extravagant world of the courts of the Valois royal family around 1400. It is made of gold, lavishly decorated with jewels and pearls, and uses the technique of enamelling en ronde bosse, or "in the round", which had been recently developed when the reliquary was made, to create a total of 28 three-dimensional figures, mostly in white enamel.

Limoges enamel has been produced at Limoges, in south-western France, over several centuries up to the present. There are two periods when it was of European importance. From the 12th century to 1370 there was a large industry producing metal objects decorated in enamel using the champlevé technique, of which most of the survivals, and probably most of the original production, are religious objects such as reliquaries.

Hedwig glasses or Hedwig beakers are a type of glass beaker originating in the Middle East or Norman Sicily and dating from the 10th-12th centuries AD. They are named after the Silesian princess Saint Hedwig (1174–1245), to whom three of them are traditionally said to have belonged. So far, a total of 14 complete glasses are known. The exact origin of the glasses is disputed, with Egypt, Iran and Syria all suggested as possible sources; if they are not of Islamic manufacture they are certainly influenced by Islamic glass. Probably made by Muslim craftsmen, some of the iconography is Christian, suggesting they may have been made for export or for Christian clients. The theory that they instead originate from Norman Sicily in the 11th century was first fully set out in a book in 2005 by Rosemarie Lierke, and has attracted some support from specialists.

In 1898 Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild bequeathed to the British Museum as the Waddesdon Bequest the contents from his New Smoking Room at Waddesdon Manor. This consisted of a wide-ranging collection of almost 300 objets d'art et de vertu, which included exquisite examples of jewellery, plate, enamel, carvings, glass and maiolica. One of the earlier objects is the outstanding Holy Thorn Reliquary, probably created in the 1390s in Paris for John, Duke of Berry. The collection is in the tradition of a schatzkammer, or treasure house, such as those formed by the Renaissance princes of Europe; indeed, the majority of the objects are from late Renaissance Europe, although there are several important medieval pieces, and outliers from classical antiquity and medieval Syria.

Enamelled glass or painted glass is glass which has been decorated with vitreous enamel and then fired to fuse the glasses. It can produce brilliant and long-lasting colours, and be translucent or opaque. Unlike most methods of decorating glass, it allows painting using several colours, and along with glass engraving, has historically been the main technique used to create the full range of image types on glass.

The miniature altarpiece in the British Museum, London, is a very small portable Gothic boxwood miniature sculpture completed in 1511 by the Northern Netherlands master sometimes identified as Adam Dircksz, and members of his workshop. At 25.1 cm (9.9 in) high, it is built from a series of architectural layers or registers, which culminate at an upper triptych, whose center panel contains a minutely detailed and intricate Crucifixion scene filled with multitudes of figures in relief. Its outer wings show Christ Carrying the Cross on the left, and the Resurrection on the right.

During the thirteenth century, Mosul, Iraq became home to a school of luxury metalwork which rose to international renown. Artifacts classified as Mosul are some of the most intricately designed and revered pieces of the Middle Ages.

The Maqāmāt al-Ḥarīrī is a collection of fifty tales or maqāmāt written at the end of the 11th or the beginning of the 12th century by al-Ḥarīrī of Basra (1054–1122), a poet and government official of the Seljuk Empire. The text presents a series of tales regarding the adventures of the fictional character Abū Zayd of Saruj who travels and deceives those around him with his skill in the Arabic language to earn rewards. Although probably less creative than the work of its precursor, Maqāmāt al-Hamadhānī, the Maqāmāt al-Ḥarīrī became extremely popular, with reports of seven hundred copies authorized by al-Ḥarīrī during his lifetime.

The Sharbush or Harbush was a special Turkic military furred hat, worn in Central Asia and the Middle East in the Middle Ages. It appears prominently in the miniatures depicting Badr al-Din Lu'lu'. It was a stiff cap of the military class, with a triangular front which was sometimes addorned with a metal plaque. It was sometimes supplemented with a small kerchief which formed a small turban, named takhfifa. The wearing of the Sharbūsh was one of the key graphical and sartorial elements to differentiate Turkic figures from Arab ones in medieval Middle-Eastern miniatures.

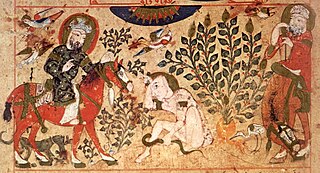

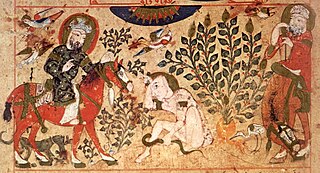

Kitāb al-Diryāq, also Book of Anditodes of Pseudo-Galen or in French Traité de la thériaque, is a medieval Arabic book supposedly based on the writings of Galen ("pseudo-Galen"). The work describes the use of Theriac, an ancient medicinal compound initially used as a cure for the bites of poisonous snakes.