Pottery, due to its relative durability, comprises a large part of the archaeological record of ancient Greece, and since there is so much of it, it has exerted a disproportionately large influence on our understanding of Greek society. The shards of pots discarded or buried in the 1st millennium BC are still the best guide available to understand the customary life and mind of the ancient Greeks. There were several vessels produced locally for everyday and kitchen use, yet finer pottery from regions such as Attica was imported by other civilizations throughout the Mediterranean, such as the Etruscans in Italy. There were a multitude of specific regional varieties, such as the South Italian ancient Greek pottery.

Black-figure pottery painting, also known as the black-figure style or black-figure ceramic, is one of the styles of painting on antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th and 5th centuries BCE, although there are specimens dating in the 2nd century BCE. Stylistically it can be distinguished from the preceding orientalizing period and the subsequent red-figure pottery style.

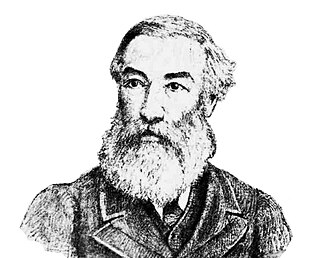

Kyriakos S. Pittakis was a Greek archaeologist. He was the first Greek to serve as Ephor General of Antiquities, the head of the Greek Archaeological Service, in which capacity he carried out the conservation and restoration of several monuments on the Acropolis of Athens. He has been described as a "dominant figure in Greek archaeology for 27 years", and as "one of the most important epigraphers of the nineteenth century".

An aryballos was a small spherical or globular flask with a narrow neck used in Ancient Greece. It was used to contain perfume or oil, and is often depicted in vase paintings being used by athletes during bathing. In these depictions, the vessel is at times attached by a strap to the athlete's wrist, or hung by a strap from a peg on the wall.

Christos Tsountas was a Greek classical archaeologist. He is considered a pioneer of Greek archaeology and has been called "the first and most eminent Greek prehistorian".

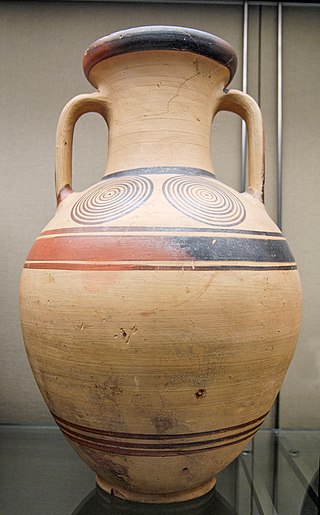

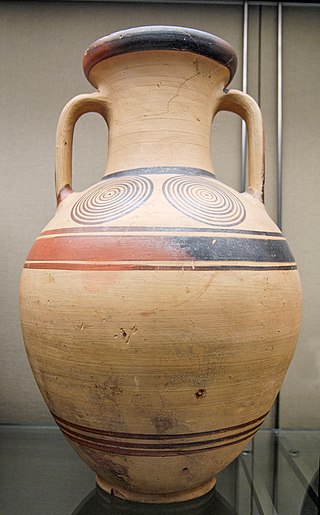

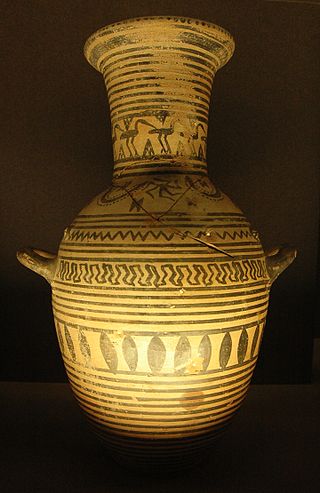

The Protogeometric style is a style of Ancient Greek pottery led by Athens and produced, in Attica and Central Greece, between roughly 1025 and 900 BCE, during the Greek Dark Ages. It was succeeded by the Early Geometric period.

Darrell Arlynn Amyx was an American classical archaeologist. His principal field of study was the archaic pottery of Corinth. Complementing the pioneering work of John Beazley and Humfry Payne, Amyx applied stylistic analysis to the work of previously unnamed and unstudied Corinthian painters, discerning many otherwise forgotten "hands".

Gryton was a Boeotian potter who worked in the first half of the 6th century BC. He is only known by his signature on the sole of a plastic aryballos in the shape of a sandal-clad foot, which is housed in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. A catalogue of his works was published by Raubitschek along with works of ancient Boeotian potters. These included the Ring Aryballos, which is part of a collection of Berlin's Staatliche Museen.

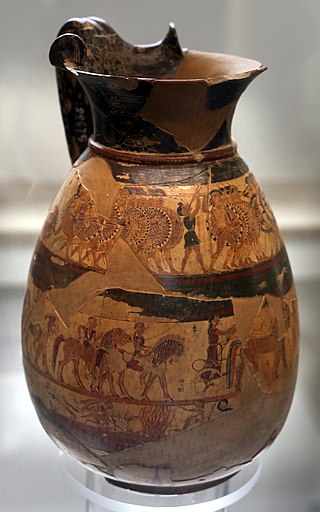

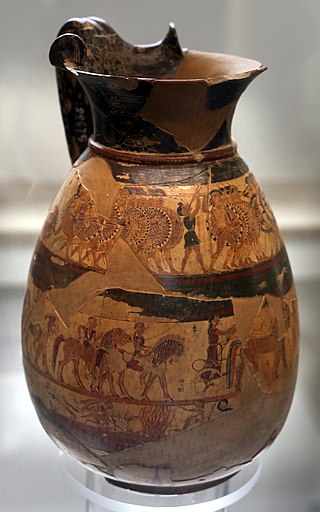

The Chigi vase is a Proto-Corinthian olpe, or pitcher, that is the name vase of the Chigi Painter. It was found in an Etruscan tomb at Monte Aguzzo, near Veio, on Prince Mario Chigi’s estate in 1881. The vase has been variously assigned to the middle and late Proto-Corinthian periods and given a date of c. 650–640 BC; it is now in the National Etruscan Museum, Villa Giulia, Rome.

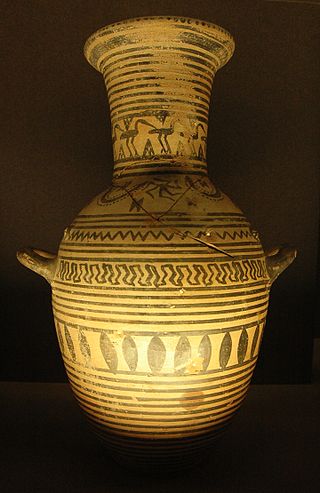

Boeotian vase painting was a regional style of ancient Greek vase painting. Since the Geometric period, and up to the 4th century BC, the region of Boeotia produced vases with ornamental and figural painted decoration, usually of lesser quality than the vase paintings from other areas.

Ludwig Ross was a German classical archaeologist. He is chiefly remembered for the rediscovery and reconstruction of the Temple of Athena Nike in 1835–1836, and for his other excavation and conservation work on the Acropolis of Athens. He was also an important figure in the early years of archaeology in the independent Kingdom of Greece, serving as Ephor General of Antiquities between 1834 and 1836.

The Greek Archaeological Service is a state service, under the auspices of the Greek Ministry of Culture, responsible for the oversight of all archaeological excavations, museums and the country's archaeological heritage in general.

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery.

The Euphiletos Painter Panathenaic Amphora is a black-figure terracotta amphora from the Archaic Period depicting a running race, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It was painted by the Euphiletos Painter as a victory prize for the Panathenaic Games in Athens in 530 BC.

The Grave Stele of Dexileos is the stele of the tomb of an Athenian cavalryman named Dexileos who died in the Corinthian War against Sparta in 394 BC. The stele is attributed to "The Dexileos Sculptor". Its creation can be dated to 394 BC, based on the inscription on its bottom, which provides the dates of birth and death of Dexileos. The stele is made out of an expensive variety of Pentelic marble and is 1.86 metres tall. It includes a high relief sculpture depicting a battle scene with an inscription below it. The stele was discovered in 1863 in the family plot of Dexileos at the Dipylon cemetery in the Kerameikos cemetery of Athens. It was found in situ, but moved during World War II, and is now on display in the Kerameikos Museum in Athens.

Panagiotis Kavvadias or Cawadias was a Greek archaeologist. He was responsible for the excavation of ancient sites in Greece, including Epidaurus in Argolis and the Acropolis of Athens, as well as archaeological discoveries on his native island of Kephallonia. As Ephor General from 1885 until 1909, Kavvadias oversaw the expansion of the Archaeological Service and the introduction of Law 2646 of 1899, which increased the state's powers to address the illegal excavation and smuggling of antiquities.

Panagiotis Antoniou Stamatakis was a Greek archaeologist. He is noted particularly for his role in supervising the excavations of Heinrich Schliemann at Mycenae in 1876, and his role in recording and preserving the archaeological remains at the site.

Panagiotis Efstratiadis or Eustratiades was a Greek archaeologist. He served as Ephor General of Antiquities, the head of the Greek Archaeological Service, between 1864 and 1884, succeeding Kyriakos Pittakis.

Athanasios Sergiou Rhousopoulos was a Greek archaeologist, antiquities dealer and university professor. He has been described as "the most important Greek collector and dealer between the 1860s and 1890s", and as "a key figure in the early days of archaeology in Greece."

Charles Louis William Merlin was a British banker, diplomat and antiquities trader. He is known for his role in procuring objects, particularly Graeco-Roman antiquities, for the British Museum.