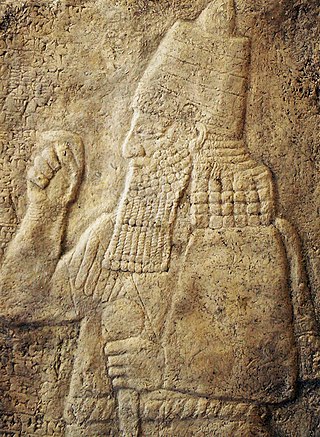

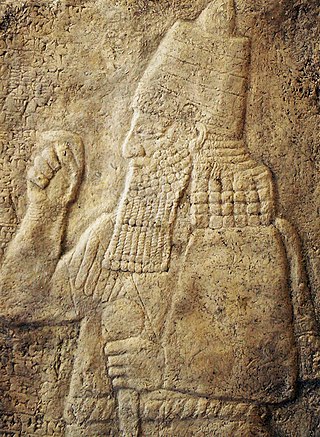

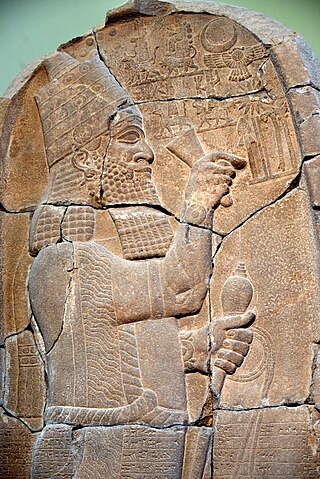

Sennacherib was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705 BC to his own death in 681 BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous Assyrian kings for the role he plays in the Hebrew Bible, which describes his campaign in the Levant. Other events of his reign include his destruction of the city of Babylon in 689 BC and his renovation and expansion of the last great Assyrian capital, Nineveh.

The 7th century BC began the first day of 700 BC and ended the last day of 601 BC.

Taharqa, also spelled Taharka or Taharqo, was a pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt and qore (king) of the Kingdom of Kush from 690 to 664 BC. He was one of the "Black Pharaohs" who ruled over Egypt for nearly a century.

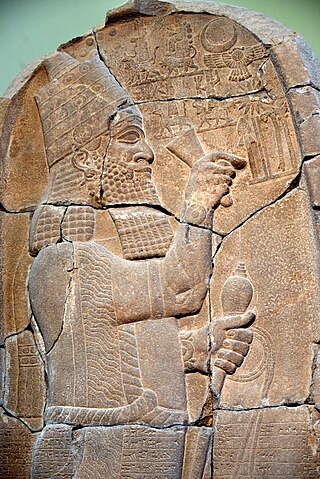

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sennacherib in 681 BC to his own death in 669. The third king of the Sargonid dynasty, Esarhaddon is most famous for his conquest of Egypt in 671 BC, which made his empire the largest the world had ever seen, and for his reconstruction of Babylon, which had been destroyed by his father.

Nabopolassar was the founder and first king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from his coronation as king of Babylon in 626 BC to his death in 605 BC. Though initially only aimed at restoring and securing the independence of Babylonia, Nabopolassar's uprising against the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which had ruled Babylonia for more than a century, eventually led to the complete destruction of the Assyrian Empire and the rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in its place.

Ashurbanipal was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the throne as the favored heir of his father Esarhaddon; his 38-year reign was among the longest of any Assyrian king. Though sometimes regarded as the apogee of ancient Assyria, his reign also marked the last time Assyrian armies waged war throughout the ancient Near East and the beginning of the end of Assyrian dominion over the region.

Sîn-šar-iškun was the penultimate king of Assyria, reigning from the death of his brother and predecessor Aššur-etil-ilāni in 627 BC to his own death at the Fall of Nineveh in 612 BC.

Wahibre Psamtik I was the first pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the Saite period, ruling from the city of Sais in the Nile delta between 664–610 BC. He was installed by Ashurbanipal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, against the Kushite rulers of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, but later gained more autonomy as the Assyrian Empire declined.

Šamaš-šuma-ukin, was king of Babylon as a vassal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 668 BC to his death in 648. Born into the Assyrian royal family, Šamaš-šuma-ukin was the son of the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon and the elder brother of Esarhaddon's successor Ashurbanipal.

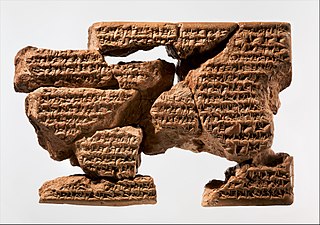

Aššur-etil-ilāni, also spelled Ashur-etel-ilani and Ashuretillilani, was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Ashurbanipal in 631 BC to his own death in 627 BC. Aššur-etil-ilāni is an obscure figure with a brief reign from which few inscriptions survive. Because of this lack of sources, very little concrete information about the king and his reign can be deduced.

Meluḫḫa or Melukhkha is the Sumerian name of a prominent trading partner of Sumer during the Middle Bronze Age. Its identification remains an open question, but most scholars associate it with the Indus Valley civilisation.

Tantamani, also known as Tanutamun or Tanwetamani was ruler of the Kingdom of Kush located in Northern Sudan, and the last pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. His prenomen or royal name was Bakare, which means "Glorious is the Soul of Re."

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East throughout much of the 8th and 7th centuries BC, becoming the largest empire in history up to that point. Because of its geopolitical dominance and ideology based in world domination, the Neo-Assyrian Empire is by many researchers regarded to have been the first world empire in history. It influenced other empires of the ancient world culturally, administratively, and militarily, including the Babylonians, the Achaemenids, and the Seleucids. At its height, the empire was the strongest military power in the world and ruled over all of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Egypt, as well as parts of Anatolia, Arabia and modern-day Iran and Armenia.

Aššur-uballiṭ II, also spelled Assur-uballit II and Ashuruballit II, was the final ruler of Assyria, ruling from his predecessor Sîn-šar-iškun's death at the Fall of Nineveh in 612 BC to his own defeat at Harran in 609 BC. He was possibly the son of Sîn-šar-iškun and likely the same person as a crown prince mentioned in inscriptions at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh in 626 and 623 BC.

The timeline of ancient Assyria can be broken down into three main eras: the Old Assyrian period, Middle Assyrian Empire, and Neo-Assyrian Empire. Modern scholars typically also recognize an Early period preceding the Old Assyrian period and a post-imperial period succeeding the Neo-Assyrian period.

The Sargonid dynasty was the final ruling dynasty of Assyria, ruling as kings of Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian Empire for just over a century from the ascent of Sargon II in 722 BC to the fall of Assyria in 609 BC. Although Assyria would ultimately fall during their rule, the Sargonid dynasty ruled the country during the apex of its power and Sargon II's three immediate successors Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal are generally regarded as three of the greatest Assyrian monarchs. Though the dynasty encompasses seven Assyrian kings, two vassal kings in Babylonia and numerous princes and princesses, the term Sargonids is sometimes used solely for Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.

The sack of Thebes took place in 663 BC in the city of Thebes at the hands of the Neo-Assyrian Empire under king Ashurbanipal, then at war with the Kushite Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt under Tantamani, during the Assyrian conquest of Egypt. After a long struggle for the control of the Levant which had started in 705 BC, the Kushites had gradually lost control of Lower Egypt and, by 665 BC, their territory was reduced to Upper Egypt and Nubia. Helped by the unreliable vassals of the Assyrians in the Nile Delta region, Tantamani briefly regained Memphis in 663 BC, killing Necho I of Sais in the process.

The Assyrian conquest of Egypt covered a relatively short period of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 673 to 663 BCE. The conquest of Egypt not only placed a land of great cultural prestige under Assyrian rule but also brought the Neo-Assyrian Empire to its greatest extent.

Nubia is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile as well as the confluence of the blue and white Niles or, more strictly, Al Dabbah. Nubia was the seat of several civilizations of ancient Africa, including the Kerma culture, the kingdom of Kush, Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia.

Ana-Tašmētum-taklāk was a queen of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. She is known only from a single fragmentary inscription and it has as of yet not been possible to confidently identify which king was her husband. She is the only Neo-Assyrian queen known by name whose husband and dates are unknown. Though various identifications have been proposed, the hypothesis with the least problems is that she was the wife of one of the last Assyrian kings, Aššur-etil-ilāni or Sîn-šar-iškun.