The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea.

A tetrapod is any four-limbed vertebrate animal of the superclass Tetrapoda. Tetrapods include all extant and extinct amphibians and amniotes, with the latter in turn evolving into two major clades, the sauropsids and synapsids. Some tetrapods, such as snakes, legless lizards, and caecilians, have evolved to become limbless via mutations of the Hox gene. Nevertheless, these limbless groups still qualify as tetrapods through their ancestry, and some retain a pair of vestigial spurs that are remnants of the hindlimbs.

The ossicles are three bones in either middle ear that are among the smallest bones in the human body. They serve to transmit sound vibrations sent from the ear drum to the fluid-filled labyrinth (cochlea). The absence of the auditory ossicles would constitute a moderate-to-severe hearing loss. The term "ossicle" literally means "tiny bone". Though the term may refer to any small bone throughout the body, it typically refers to the malleus, incus, and stapes of the middle ear.

Synapsida is one of the two major clades of vertebrate animals in the group Amniota, the other being the Sauropsida. The synapsids were the dominant land animals in the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic, but the only group that survived into the Cenozoic are mammals. Unlike other amniotes, synapsids have a single temporal fenestra, an opening low in the skull roof behind each eye orbit, leaving a bony arch beneath each; this accounts for their name. The distinctive temporal fenestra developed about 318 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period, when synapsids and sauropsids diverged, but was subsequently merged with the orbit in early mammals.

The jaws are a pair of opposable articulated structures at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term jaws is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serving to open and close it and is part of the body plan of humans and most animals.

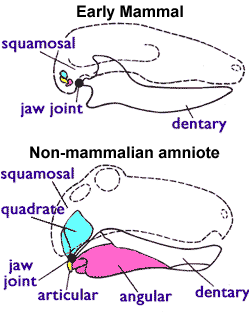

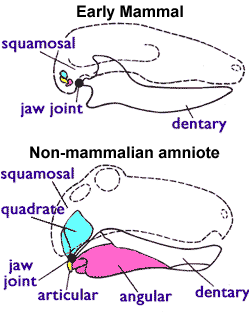

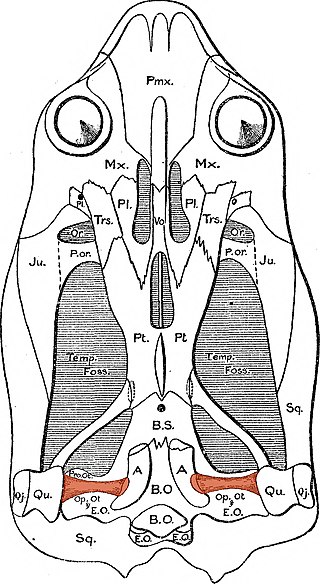

Probainognathus meaning “progressive jaw” is an extinct genus of cynodonts that lived around 235 to 221.5 million years ago, during the Late Triassic in what is now Argentina. Together with the genus Bonacynodon from Brazil, Probainognathus forms the family Probainognathidae. Probainognathus was a relatively small, carnivorous or insectivorous cynodont. Like all cynodonts, it was a relative of mammals, and it possessed several mammal-like features. Like some other cynodonts, Probainognathus had a double jaw joint, which not only included the quadrate and articular bones like in more basal synapsids, but also the squamosal and surangular bones. A joint between the dentary and squamosal bones, as seen in modern mammals, was however absent in Probainognathus.

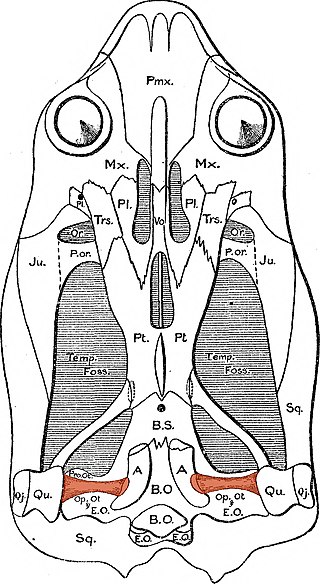

The quadratojugal is a skull bone present in many vertebrates, including some living reptiles and amphibians.

The articular bone is part of the lower jaw of most vertebrates, including most jawed fish, amphibians, birds and various kinds of reptiles, as well as ancestral mammals.

Sinoconodon is an extinct genus of mammaliamorphs that appears in the fossil record of the Lufeng Formation of China in the Sinemurian stage of the Early Jurassic period, about 193 million years ago. While sharing many plesiomorphic traits with other non-mammaliaform cynodonts, it possessed a special, secondarily evolved jaw joint between the dentary and the squamosal bones, which in more derived taxa would replace the primitive tetrapod one between the articular and quadrate bones. The presence of a dentary-squamosal joint is a trait historically used to define mammals.

In humans, the cartilaginous bar of the mandibular arch is formed by what are known as Meckel's cartilages also known as Meckelian cartilages; above this the incus and malleus are developed. Meckel's cartilage arises from the first pharyngeal arch.

The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

The evolution of mammalian auditory ossicles was an evolutionary process that resulted in the formation of the bones of the mammalian middle ear. These bones, or ossicles, are a defining characteristic of all mammals. The event is well-documented and important as a demonstration of transitional forms and exaptation, the re-purposing of existing structures during evolution.

The splanchnocranium is the portion of the cranium that is derived from pharyngeal arches. Splanchno indicates to the gut because the face forms around the mouth, which is an end of the gut. The splanchnocranium consists of cartilage and endochondral bone. In mammals, the splanchnocranium comprises the three ear ossicles, as well as the alisphenoid, the styloid process, the hyoid apparatus, and the thyroid cartilage.

Glanosuchus is a genus of scylacosaurid therocephalian from the Late Permian of South Africa. The type species G. macrops was named by Robert Broom in 1904. Glanosuchus had a middle ear structure that was intermediate between that of early therapsids and mammals. Ridges in the nasal cavity of Glanosuchus suggest it had an at least partially endothermic metabolism similar to modern mammals.

Cranial kinesis is the term for significant movement of skull bones relative to each other in addition to movement at the joint between the upper and lower jaws. It is usually taken to mean relative movement between the upper jaw and the braincase.

Reptiles arose about 320 million years ago during the Carboniferous period. Reptiles, in the traditional sense of the term, are defined as animals that have scales or scutes, lay land-based hard-shelled eggs, and possess ectothermic metabolisms. So defined, the group is paraphyletic, excluding endothermic animals like birds that are descended from early traditionally-defined reptiles. A definition in accordance with phylogenetic nomenclature, which rejects paraphyletic groups, includes birds while excluding mammals and their synapsid ancestors. So defined, Reptilia is identical to Sauropsida.

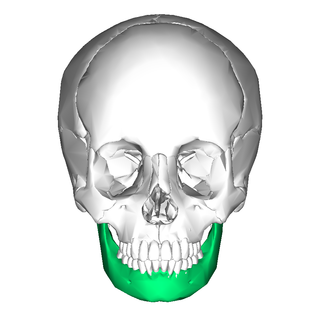

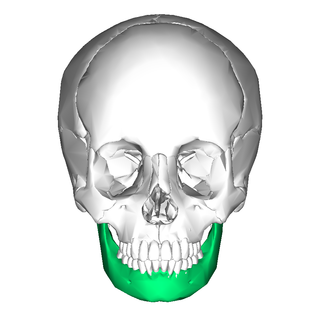

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible, lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lower – and typically more mobile – component of the mouth.

In the auditory system, the columella contributes to hearing in amphibians, reptiles and birds. The columella form thin, bony structures in the interior of the skull and serve the purpose of transmitting sounds from the eardrum. It is an evolutionary homolog of the stapes, one of the auditory ossicles in mammals.

Most bony fishes have two sets of jaws made mainly of bone. The primary oral jaws open and close the mouth, and a second set of pharyngeal jaws are positioned at the back of the throat. The oral jaws are used to capture and manipulate prey by biting and crushing. The pharyngeal jaws, so-called because they are positioned within the pharynx, are used to further process the food and move it from the mouth to the stomach.

This glossary explains technical terms commonly employed in the description of dinosaur body fossils. Besides dinosaur-specific terms, it covers terms with wider usage, when these are of central importance in the study of dinosaurs or when their discussion in the context of dinosaurs is beneficial. The glossary does not cover ichnological and bone histological terms, nor does it cover measurements.