Valerian is a perennial flowering plant native to Europe and Asia. In the summer when the mature plant may have a height of 1.5 metres (5 ft), it bears sweetly scented pink or white flowers that attract many fly species, especially hoverflies of the genus Eristalis. It is consumed as food by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species, including the grey pug.

Sassafras is a genus of three extant and one extinct species of deciduous trees in the family Lauraceae, native to eastern North America and eastern Asia. The genus is distinguished by its aromatic properties, which have made the tree useful to humans.

Bearberries are three species of dwarf shrubs in the genus Arctostaphylos. Unlike the other species of Arctostaphylos, they are adapted to Arctic and Subarctic climates, and have a circumpolar distribution in northern North America, Asia and Europe.

Herbal medicine is the use of plants with presumed therapeutic properties as a basis of traditional medicine. Herbalism may be part of pharmacognosy – the study of plants or other natural sources as a possible source of drugs. The scope of herbal medicine commonly includes fungal and bee products, as well as minerals, shells and certain animal parts. Herbal medicine is also called phytomedicine or phytotherapy.

Ginseng is the root of plants in the genus Panax, such as Korean ginseng, South China ginseng, and American ginseng, typically characterized by the presence of ginsenosides and gintonin.

Medicinal plants, also called medicinal herbs, have been discovered and used in traditional medicine practices since prehistoric times. Plants synthesise hundreds of chemical compounds for functions including defence against insects, fungi, diseases, and herbivorous mammals. Numerous phytochemicals with potential or established biological activity have been identified. However, since a single plant contains widely diverse phytochemicals, the effects of using a whole plant as medicine are uncertain. Further, the phytochemical content and pharmacological actions, if any, of many plants having medicinal potential remain unassessed by rigorous scientific research to define efficacy and safety.

Rhamnus is a genus of about 110 accepted species of shrubs or small trees, commonly known as buckthorns, in the family Rhamnaceae. Its species range from 1 to 10 m tall and are native mainly in east Asia and North America, but found throughout the temperate and subtropical Northern Hemisphere, and also more locally in the subtropical Southern Hemisphere in parts of Africa and South America. One species, the common buckthorn, was able to flourish as an invasive plant in parts of Canada and the U.S.

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi is a plant species of the genus Arctostaphylos widely distributed across circumboreal regions of the subarctic Northern Hemisphere. Kinnikinnick is a common name in Canada and the United States. It is one of several related species referred to as bearberry.

Frangula is a genus of about 35 species of flowering shrubs or small trees, commonly known as alder buckthorn in the buckthorn family Rhamnaceae. The common name buckthorn is also used to describe species of the genus Rhamnus in the same family and also sea-buckthorn, Hippophae rhamnoides in the Elaeagnaceae.

Frangula californica is a species of flowering plant in the buckthorn family native to western North America. It produces edible fruits and seeds. It is commonly known as California coffeeberry and California buckthorn.

Sassafras albidum is a species of Sassafras native to eastern North America, from southern Maine and southern Ontario west to Iowa, and south to central Florida and eastern Texas. It occurs throughout the eastern deciduous forest habitat type, at altitudes of up to 1,500 m above sea level. It formerly also occurred in southern Wisconsin, but is extirpated there as a native tree.

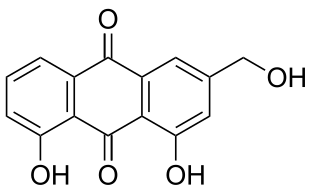

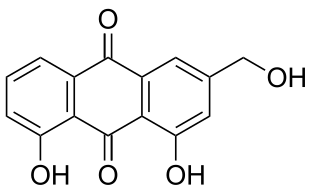

Emodin (6-methyl-1,3,8-trihydroxyanthraquinone) is a chemical compound, of the anthraquinone family, that can be isolated from rhubarb, buckthorn, and Japanese knotweed. Emodin is particularly abundant in the roots of the Chinese rhubarb, knotweed and knotgrass as well as Hawaii ‘au‘auko‘i cassia seeds or coffee weed. It is specifically isolated from Rheum Palmatum L. It is also produced by many species of fungi, including members of the genera Aspergillus, Pyrenochaeta, and Pestalotiopsis, inter alia. The common name is derived from Rheum emodi, a taxonomic synonym of Rheum australe, and synonyms include emodol, frangula emodin, rheum emodin, 3-methyl-1,6,8-trihydroxyanthraquinone, Schuttgelb, and Persian Berry Lake.

Rhamnus cathartica, the European buckthorn, common buckthorn, purging buckthorn, or just buckthorn, is a species of small tree in the flowering plant family Rhamnaceae. It is native to Europe, northwest Africa and western Asia, from the central British Isles south to Morocco, and east to Kyrgyzstan. It was introduced to North America as an ornamental shrub in the early 19th century or perhaps before, and is now naturalized in the northern half of the continent, and is classified as an invasive plant in several US states and in Ontario, Canada.

Frangula alnus, commonly known as alder buckthorn, glossy buckthorn, or breaking buckthorn, is a tall deciduous shrub in the family Rhamnaceae. Unlike other "buckthorns", alder buckthorn does not have thorns. It is native to Europe, northernmost Africa, and western Asia, from Ireland and Great Britain north to the 68th parallel in Scandinavia, east to central Siberia and Xinjiang in western China, and south to northern Morocco, Turkey, and the Alborz in Iran and Caucasus Mountains; in the northwest of its range, it is rare and scattered. It is also introduced and naturalised in eastern North America.

Aloe emodin is an anthraquinone and a variety of emodin present in aloe latex, an exudate from the aloe plant. It has a strong stimulant-laxative action. Aloe emodin is not carcinogenic when applied to the skin, although it may increase the carcinogenicity of some kind of radiation.

In general use, herbs are plants with savory or aromatic properties that are used for flavoring and garnishing food, for medicinal purposes, or for fragrances; excluding vegetables and other plants consumed for macronutrients. Culinary use typically distinguishes herbs from spices. Herbs generally refers to the leafy green or flowering parts of a plant, while spices are usually dried and produced from other parts of the plant, including seeds, bark, roots and fruits.

Coffee cherry tea is a herbal tea made from the dried skins of the coffee fruit. Often it is more than the skins that are used, and include the dried berries of the coffee plant that remain after the coffee beans have been collected from within. It is also known as cascara, from the Spanish cáscara, meaning "husk". It is different from cáscara sagrada tea, a powerful plant-based laxative derived from Rhamnus purshiana, which is native to the Pacific Northwest.

Frangula betulifolia, the birchleaf buckthorn, is a shrub or small tree in the buckthorn family, Rhamnaceae. It is native in northern Mexico in the Sierra Madre Occidental cordillera, and mountainous, desert regions of the Southwestern United States of Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and far west Texas; besides being found in Sonora, Chihuahua and Durango of the Occidental cordillera, a large species locale occurs to the east in Nuevo León.

Brazilian tea culture has its origins in the infused beverages, or chás, made by the indigenous cultures of the Amazon region and the Rio da Prata basin. It has evolved since the Portuguese colonial period to include imported varieties and tea-drinking customs. There is a popular belief in Brazil that Brazilians, especially the urban ones, have a greater taste for using sugar in teas than in other cultures, being unused to unsweetened drinks.

This is a list of plants used by the indigenous people of North America. For lists pertaining specifically to the Cherokee, Iroquois, Navajo, and Zuni, see Cherokee ethnobotany, Iroquois ethnobotany, Navajo ethnobotany, and Zuni ethnobotany.