Skinks are lizards belonging to the family Scincidae, a family in the infraorder Scincomorpha. With more than 1,500 described species across 100 different taxonomic genera, the family Scincidae is one of the most diverse families of lizards. Skinks are characterized by their smaller legs in comparison to typical lizards and are found in different habitats except arctic and subarctic regions.

Egernia is a genus of skinks that occurs in Australia. These skinks are ecologically diverse omnivores that inhabit a wide range of habitats. However, in the loose delimitation the genus is not monophyletic but an evolutionary grade, as has long been suspected due to its lack of characteristic apomorphies.

Eulamprus is a genus of lizards, commonly known as water skinks, in the subfamily Sphenomorphinae of the family Scincidae. The genus is native to Australia.

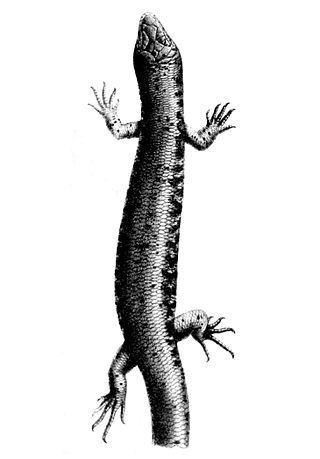

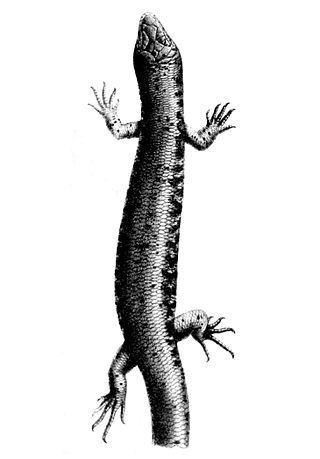

Lygosoma is a genus of lizards, commonly known as supple skinks or writhing skinks, which are members of the family Scincidae. Lygosoma is the type genus of the subfamily Lygosominae. The common name, writhing skinks, refers to the way these stubby-legged animals move, snake-like but more slowly and more awkwardly.

In animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the mother, with the maternal circulation providing for the metabolic needs of the embryo's development, until the mother gives birth to a fully or partially developed juvenile that is at least metabolically independent. This is opposed to oviparity, where the embryos develop independently outside the mother in eggs until they are developed enough to break out as hatchlings; and ovoviviparity, where the embryos are developed in eggs that remain carried inside the mother's body until the hatchlings emerge from the mother as juveniles, similar to a live birth.

Oviparous animals are animals that reproduce by depositing fertilized zygotes outside the body in metabolically independent incubation organs known as eggs, which nurture the embryo into moving offsprings known as hatchlings with little or no embryonic development within the mother. This is the reproductive method used by most animal species, as opposed to viviparous animals that develop the embryos internally and metabolically dependent on the maternal circulation, until the mother gives birth to live juveniles.

Lygosominae is the largest subfamily of skinks in the family Scincidae. The subfamily can be divided into a number of genus groups. If the rarely used taxonomic rank of infrafamily is employed, the genus groups would be designated as such, but such a move would require a formal description according to the ICZN standards.

Bougainville's skink is a species of skink, a lizard in the family Scincidae. This species is also commonly called the south-eastern slider and Bougainville's lerista.

The eastern three-lined skink, also known commonly as the bold-striped cool-skink, is a species of skink, a lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is endemic to Australia. A. duperreyi has been extensively studied in the context of understanding the evolution of learning, viviparity in lizards, and temperature- and genetic-sex determination. A. duperreyi is classified as a species of "Least Concern" by the IUCN.

Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii, also known commonly as Entrecasteaux's skink, the southern grass skink, the tussock cool-skink, and the tussock skink, is a species of lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is endemic to Australia.

Oligosoma suteri, known commonly as Suter's skink, the black shore skink, the egg-laying skink, and Suter's ground skink, is a species of lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is endemic to New Zealand.

Chioninia is a genus of skinks, lizards in the subfamily Lygosominae. For long, this genus was included in the "wastebin taxon" Mabuya. The genus Chioninia contains the Cape Verde mabuyas.

Lankascincus deignani, commonly known as Deignan's tree skink and the Deignan tree skink, is a species of lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is endemic to the island of Sri Lanka.

Lankascincus dorsicatenatus, also known as the catenated lankaskink, is a species of skink, a lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is endemic to island of Sri Lanka.

Concinnia is a genus of skinks in the subfamily Lygosominae.

Kaestlea is a genus of skinks. These skinks are small, shiny, smooth-scaled species. They are diurnal, terrestrial and insectivorous. They lay eggs to reproduce. These skinks are identified by their distinct blue tail colour. They live in tropical rainforest and montane forest habitats. These secretive skinks silently move through thick leaf-litter on forest floor. They are all endemic to the Western Ghats mountains and in some parts of Eastern Ghats (Shevaroys) of South India.

Egernia stokesii is a gregarious species of lizard of the Scincidae family. This diurnal species is endemic to Australia, and is also known as the Gidgee skink, spiny-tailed skink, Stokes's skink and Stokes's egernia. The species forms stable, long-term social aggregations, much like the social groups seen in mammalian and avian species. This characteristic is rarely found in the Squamata order, but is widespread within the Australian subfamily of Egerniinae skinks. Populations of E. stokesii are widely distributed, but fragmented, and occur in semi-arid environments. There are three recognised subspecies. The conservation status for the species is listed as least concern, however, one subspecies is listed as endangered.

Sphenomorphinae is a large subfamily of skinks, lizards within the family Scincidae. The genera in this subfamily were previously found to belong to the Sphenomorphus group in the large subfamily Lygosominae.

Silvascincus tryoni, the Border Ranges blue-spectacled skink or forest skink, is a species of lizard in the family Scincidae. It is endemic to the McPherson Range bordering New South Wales and Queensland, Australia.

Sphenomorphus derooyae is a species of skink, a lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is native to Oceania.