Related Research Articles

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a type of severe skin reaction. Together with toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens–Johnson/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) overlap, they are considered febrile mucocutaneous drug reactions and probably part of the same spectrum of disease, with SJS being less severe. Erythema multiforme (EM) is generally considered a separate condition. Early symptoms of SJS include fever and flu-like symptoms. A few days later, the skin begins to blister and peel, forming painful raw areas. Mucous membranes, such as the mouth, are also typically involved. Complications include dehydration, sepsis, pneumonia and multiple organ failure.

In immunology, autoimmunity is the system of immune responses of an organism against its own healthy cells, tissues and other normal body constituents. Any disease resulting from this type of immune response is termed an "autoimmune disease". Prominent examples include celiac disease, diabetes mellitus type 1, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Graves' disease, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, Addison's disease, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and multiple sclerosis. Autoimmune diseases are very often treated with steroids.

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. These cell surface proteins are called MHC molecules.

Allopurinol is a medication used to decrease high blood uric acid levels. It is specifically used to prevent gout, prevent specific types of kidney stones and for the high uric acid levels that can occur with chemotherapy. It is taken orally or intravenously.

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system or complex of genes on chromosome 6 in humans which encode cell-surface proteins responsible for regulation of the immune system. The HLA system is also known as the human version of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) found in many animals.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a type of severe skin reaction. Together with Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) it forms a spectrum of disease, with TEN being more severe. Early symptoms include fever and flu-like symptoms. A few days later the skin begins to blister and peel forming painful raw areas. Mucous membranes, such as the mouth, are also typically involved. Complications include dehydration, sepsis, pneumonia, and multiple organ failure.

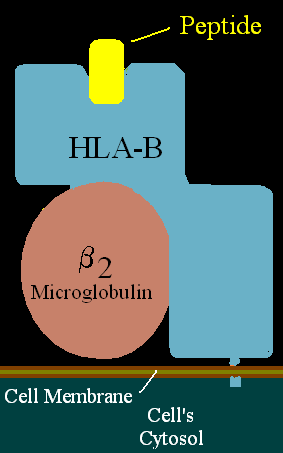

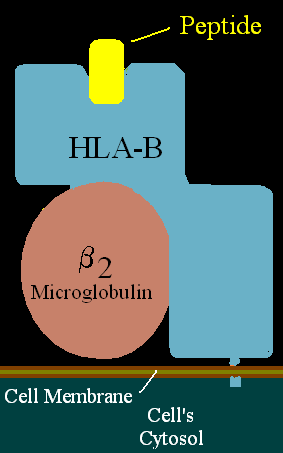

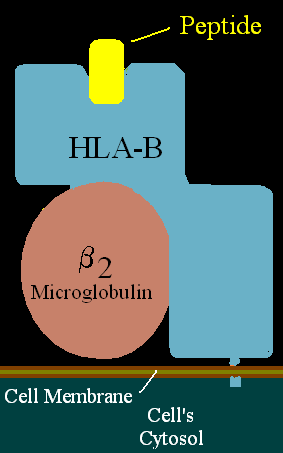

HLA-B is a human gene that provides instructions for making a protein that plays a critical role in the immune system. HLA-B is part of a family of genes called the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex. The HLA complex helps the immune system distinguish the body's own proteins from proteins made by foreign invaders such as viruses and bacteria.

Immunogenicity is the ability of a foreign substance, such as an antigen, to provoke an immune response in the body of a human or other animal. It may be wanted or unwanted:

HLA-DQ (DQ) is a cell surface receptor protein found on antigen-presenting cells. It is an αβ heterodimer of type MHC class II. The α and β chains are encoded by two loci, HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1, that are adjacent to each other on chromosome band 6p21.3. Both α-chain and β-chain vary greatly. A person often produces two α-chain and two β-chain variants and thus 4 isoforms of DQ. The DQ loci are in close genetic linkage to HLA-DR, and less closely linked to HLA-DP, HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C.

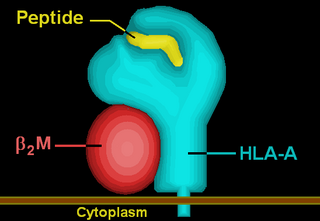

HLA-A is a group of human leukocyte antigens (HLA) that are encoded by the HLA-A locus, which is located at human chromosome 6p21.3. HLA is a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigen specific to humans. HLA-A is one of three major types of human MHC class I transmembrane proteins. The others are HLA-B and HLA-C. The protein is a heterodimer, and is composed of a heavy α chain and smaller β chain. The α chain is encoded by a variant HLA-A gene, and the β chain (β2-microglobulin) is an invariant β2 microglobulin molecule. The β2 microglobulin protein is encoded by the B2M gene, which is located at chromosome 15q21.1 in humans.

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also termed drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), is a rare reaction to certain medications. It involves primarily a widespread skin rash, fever, swollen lymph nodes, and characteristic blood abnormalities such as an abnormally high level of eosinophils, low number of platelets, and increased number of atypical white blood cells (lymphocytes). However, DRESS is often complicated by potentially life-threatening inflammation of internal organs and the syndrome has about a 10% mortality rate. Treatment consists of stopping the offending medication and providing supportive care. Systemic corticosteroids are commonly used as well but no controlled clinical trials have assessed the efficacy of this treatment.

HLA-B58 (B58) is an HLA-B serotype. B58 is a split antigen from the B17 broad antigen, the sister serotype B57. The serotype identifies the more common HLA-B*58 gene products. B*5801 is associated with allopurinol induced inflammatory necrotic skin disease.

HLA-B57 (B57) is an HLA-B serotype. B57 is a split antigen from the B17 broad antigen, the sister serotype being B58. The serotype identifies the more common HLA-B*57 gene products. Like B58, B57 is involved in drug-induced inflammatory skin disorders.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to immunology:

In medicine, a drug eruption is an adverse drug reaction of the skin. Most drug-induced cutaneous reactions are mild and disappear when the offending drug is withdrawn. These are called "simple" drug eruptions. However, more serious drug eruptions may be associated with organ injury such as liver or kidney damage and are categorized as "complex". Drugs can also cause hair and nail changes, affect the mucous membranes, or cause itching without outward skin changes.

Allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome(AHS) typically occurs in persons with preexisting kidney failure. Weeks to months after allopurinol is begun, the patient develops a morbilliform eruption or, less commonly, develops one of the far more serious and potentially lethal severe cutaneous adverse reactions viz., the DRESS syndrome, Stevens Johnson syndrome, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. About 1 in 1000 patients receiving allopurinol are affected, and mortality rates have been reported to be between 20% and 25%.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a rare skin reaction that in 90% of cases is related to medication.

Peptide-based synthetic vaccines are subunit vaccines made from peptides. The peptides mimic the epitopes of the antigen that triggers direct or potent immune responses. Peptide vaccines can not only induce protection against infectious pathogens and non-infectious diseases but also be utilized as therapeutic cancer vaccines, where peptides from tumor-associated antigens are used to induce an effective anti-tumor T-cell response.

The p-i concept refers to the pharmacological interaction of drugs with immune receptors. It explains a form of drug hypersensitivity, namely T cell stimulation, which can lead to various acute inflammatory manifestations such as exanthems, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal nercrolysis, and complications upon withdrawing the drug.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Adler NR, Aung AK, Ergen EN, Trubiano J, Goh MS, Phillips EJ (2017). "Recent advances in the understanding of severe cutaneous adverse reactions". The British Journal of Dermatology. 177 (5): 1234–1247. doi:10.1111/bjd.15423. PMC 5582023 . PMID 28256714.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hoetzenecker W, Nägeli M, Mehra ET, Jensen AN, Saulite I, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Guenova E, Cozzio A, French LE (2016). "Adverse cutaneous drug eruptions: current understanding". Seminars in Immunopathology. 38 (1): 75–86. doi:10.1007/s00281-015-0540-2. PMID 26553194. S2CID 333724.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Garon SL, Pavlos RK, White KD, Brown NJ, Stone CA, Phillips EJ (2017). "Pharmacogenomics of off-target adverse drug reactions". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 83 (9): 1896–1911. doi:10.1111/bcp.13294. PMC 5555876 . PMID 28345177.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cho YT, Yang CW, Chu CY (2017). "Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS): An Interplay among Drugs, Viruses, and Immune System". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (6): 1243. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061243 . PMC 5486066 . PMID 28598363.

- 1 2 Pichler WJ, Hausmann O (2016). "Classification of Drug Hypersensitivity into Allergic, p-i, and Pseudo-Allergic Forms". International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 171 (3–4): 166–179. doi: 10.1159/000453265 . PMID 27960170.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lerch M, Mainetti C, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Harr T (2017). "Current Perspectives on Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis". Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 54 (1): 147–176. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8654-z. PMID 29188475. S2CID 46796285.

- ↑ Schneider JA, Cohen PR (2017). "Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Concise Review with a Comprehensive Summary of Therapeutic Interventions Emphasizing Supportive Measures". Advances in Therapy. 34 (6): 1235–1244. doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0530-y. PMC 5487863 . PMID 28439852.

- ↑ Uzzaman A, Cho SH (2012). "Chapter 28: Classification of hypersensitivity reactions". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 33 Suppl 1 (3): S96–9. doi:10.2500/aap.2012.33.3561. PMID 22794701. S2CID 207394296.

- ↑ Corneli HM (2017). "DRESS Syndrome: Drug Reaction With Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms". Pediatric Emergency Care. 33 (7): 499–502. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001188. PMID 28665896.

- 1 2 Adwan MH (2017). "Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) Syndrome and the Rheumatologist". Current Rheumatology Reports. 19 (1): 3. doi:10.1007/s11926-017-0626-z. PMID 28138822. S2CID 10549742.

- 1 2 3 Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N (2016). "Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: Pathogenesis, Genetic Background, Clinical Variants and Therapy". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 17 (8): 1214. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081214 . PMC 5000612 . PMID 27472323.

- ↑ Alniemi DT, Wetter DA, Bridges AG, El-Azhary RA, Davis MD, Camilleri MJ, McEvoy MT (2017). "Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, treatments, and outcomes in a series of 28 patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996-2013". International Journal of Dermatology. 56 (4): 405–414. doi:10.1111/ijd.13434. PMID 28084022. S2CID 21325754.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O (2017). "Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs". Lancet. 390 (10106): 1996–2011. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30378-6. PMID 28476287. S2CID 9506967.

- ↑ Fan WL, Shiao MS, Hui RC, Su SC, Wang CW, Chang YC, Chung WH (2017). "HLA Association with Drug-Induced Adverse Reactions". Journal of Immunology Research. 2017: 3186328. doi: 10.1155/2017/3186328 . PMC 5733150 . PMID 29333460.

- ↑ Wang CW, Dao RL, Chung WH (2016). "Immunopathogenesis and risk factors for allopurinol severe cutaneous adverse reactions". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 16 (4): 339–45. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000286. PMID 27362322. S2CID 9183824.

- 1 2 Chung WH, Wang CW, Dao RL (July 2016). "Severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions". The Journal of Dermatology. 43 (7): 758–66. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13430. PMID 27154258. S2CID 45524211.

- ↑ Chong HY, Mohamed Z, Tan LL, Wu DB, Shabaruddin FH, Dahlui M, Apalasamy YD, Snyder SR, Williams MS, Hao J, Cavallari LH, Chaiyakunapruk N (2017). "Is universal HLA-B*15:02 screening a cost-effective option in an ethnically diverse population? A case study of Malaysia". The British Journal of Dermatology. 177 (4): 1102–1112. doi:10.1111/bjd.15498. PMC 5617756 . PMID 28346659.

- 1 2 Su SC, Hung SI, Fan WL, Dao RL, Chung WH (2016). "Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions: The Pharmacogenomics from Research to Clinical Implementation". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 17 (11): 1890. doi: 10.3390/ijms17111890 . PMC 5133889 . PMID 27854302.