Astrometry is the branch of astronomy that involves precise measurements of the positions and movements of stars and other celestial bodies. The information obtained by astrometric measurements provides information on the kinematics and physical origin of the Solar System and our galaxy, the Milky Way.

A sextant is a doubly reflecting navigation instrument that measures the angular distance between two visible objects. The primary use of a sextant is to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon for the purposes of celestial navigation.

Mīrzā Muhammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrukh, better known as Ulugh Beg, was a Timurid sultan, as well as an astronomer and mathematician.

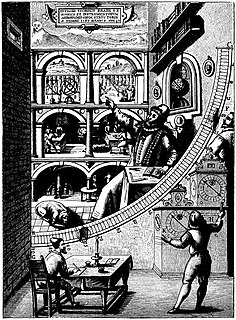

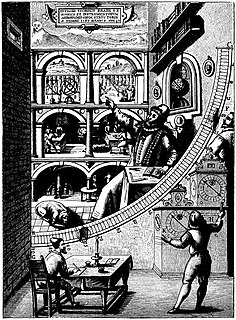

Uraniborg was a Danish astronomical observatory and alchemy laboratory established and operated by Tycho Brahe. It was built c. 1576 – c. 1580 on Hven, an island in the Øresund between Zealand and Scania, Sweden, which was part of Denmark at the time. It was expanded with the underground facility Stjerneborg on an adjacent site.

An alidade or a turning board is a device that allows one to sight a distant object and use the line of sight to perform a task. This task can be, for example, to draw a line on a plane table in the direction of the object or to measure the angle to the object from some reference point. Angles measured can be horizontal, vertical or in any chosen plane.

The backstaff is a navigational instrument that was used to measure the altitude of a celestial body, in particular the Sun or Moon. When observing the Sun, users kept the Sun to their back and observed the shadow cast by the upper vane on a horizon vane. It was invented by the English navigator John Davis, who described it in his book Seaman's Secrets in 1594.

The Constantinople observatory of Taqi ad-Din, founded in Constantinople by Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf in 1577, was one of the largest astronomical observatories in medieval world. However, it only existed for a few years and was destroyed in 1580.

The triquetrum was the medieval name for an ancient astronomical instrument first described by Ptolemy in the Almagest. Also known as Parallactic Rulers, it was used for determining altitudes of heavenly bodies. Ptolemy calls it a "parallactic instrument" and seems to have used it to determine the zenith distance and parallax of the Moon.

The term Jacob's staff, also known as cross-staff, a ballastella, a fore-staff, or a balestilha, is used to refer to several things. In its most basic form, a Jacob's staff is a stick or pole with length markings; most staffs are much more complicated than that, and usually contain a number of measurement and stabilization features. The two most frequent uses are:

The octant, also called reflecting quadrant, is a measuring instrument used primarily in navigation. It is a type of reflecting instrument.

The meridian circle is an instrument for timing of the passage of stars across the local meridian, an event known as a culmination, while at the same time measuring their angular distance from the nadir. These are special purpose telescopes mounted so as to allow pointing only in the meridian, the great circle through the north point of the horizon, the north celestial pole, the zenith, the south point of the horizon, the south celestial pole, and the nadir. Meridian telescopes rely on the rotation of the sky to bring objects into their field of view and are mounted on a fixed, horizontal, east–west axis.

Celestial cartography, uranography, astrography or star cartography is the fringe of astronomy and branch of cartography concerned with mapping stars, galaxies, and other astronomical objects on the celestial sphere. Measuring the position and light of charted objects requires a variety of instruments and techniques. These techniques have developed from angle measurements with quadrants and the unaided eye, through sextants combined with lenses for light magnification, up to current methods which include computer-automated space telescopes. Uranographers have historically produced planetary position tables, star tables, and star maps for use by both amateur and professional astronomers. More recently computerized star maps have been compiled, and automated positioning of telescopes is accomplished using databases of stars and other astronomical objects.

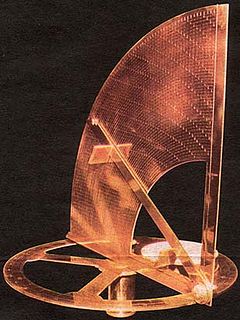

The mariner's astrolabe, also called sea astrolabe, was an inclinometer used to determine the latitude of a ship at sea by measuring the sun's noon altitude (declination) or the meridian altitude of a star of known declination. Not an astrolabe proper, the mariner's astrolabe was rather a graduated circle with an alidade used to measure vertical angles. They were designed to allow for their use on boats in rough water and/or in heavy winds, which astrolabes are ill-equipped to handle. In the sixteenth century, the instrument was also called a ring.

A mural instrument is an angle measuring device mounted on or built into a wall. For astronomical purposes, these walls were oriented so they lie precisely on the meridian. A mural instrument that measured angles from 0 to 90 degrees was called a mural quadrant. They were utilized as astronomical devices in ancient Egypt and ancient Greece. Edmond Halley, due to the lack of an assistant and only one vertical wire in his transit, confined himself to the use of a mural quadrant built by George Graham after its erection in 1725 at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. Bradley's first observation with that quadrant was made on 15 June 1742.

A dividing engine is a device employed to mark graduations on measuring instruments to allow for reading smaller measurements than can be allowed by directly engraving them. The well-known vernier scale and micrometer screw-gauge are classic examples that make use of such graduations.

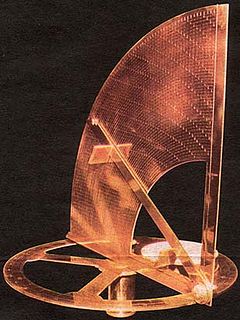

A quadrant is an instrument that is used to measure angles up to 90°. Different versions of this instrument could be used to calculate various readings, such as longitude, latitude, and time of day. It was originally proposed by Ptolemy as a better kind of astrolabe. Several different variations of the instrument were later produced by medieval Muslim astronomers.

Transversals are a geometric construction on a scientific instrument to allow a graduation to be read to a finer degree of accuracy. Transversals have been replaced in modern times by vernier scales. This method is based on the Intercept theorem.

Reflecting instruments are those that use mirrors to enhance their ability to make measurements. In particular, the use of mirrors permits one to observe two objects simultaneously while measuring the angular distance between the objects. While reflecting instruments are used in many professions, they are primarily associated with celestial navigation as the need to solve navigation problems, in particular the problem of the longitude, was the primary motivation in their development.

An Elton's quadrant is a derivative of the Davis quadrant. It adds an index arm and artificial horizon to the instrument. It was invented by John Elton a sea captain who patented his design in 1728 and published details of the instrument in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1732.

Nonius is a measuring tool used in navigation and astronomy named in honour of its inventor, Pedro Nunes, a Portuguese author, mathematician and navigator. The nonius was created in 1542 as a system for taking finer measurements on circular instruments such as the astrolabe. The system was eventually adapted into the Vernier scale in 1631 by the French mathematician Pierre Vernier.