Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, formerly sometimes spelled de la Caille, was a French astronomer and geodesist who named 14 out of the 88 constellations. From 1750 to 1754, he studied the sky at the Cape of Good Hope in present-day South Africa. Lacaille observed over 10,000 stars using a refracting telescope.

A star catalogue is an astronomical catalogue that lists stars. In astronomy, many stars are referred to simply by catalogue numbers. There are a great many different star catalogues which have been produced for different purposes over the years, and this article covers only some of the more frequently quoted ones. Star catalogues were compiled by many different ancient people, including the Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese, Persians, and Arabs. They were sometimes accompanied by a star chart for illustration. Most modern catalogues are available in electronic format and can be freely downloaded from space agencies' data centres. The largest is being compiled from the spacecraft Gaia and thus far has over a billion stars.

Mīrzā Muhammad Tarāghāy bin Shāhrukh, better known as Ulugh Beg, was a Timurid sultan, as well as an astronomer and mathematician.

Albert Brudzewski, alsoAlbert Blar (of Brudzewo), Albert of Brudzewo or Wojciech Brudzewski (in Latin, Albertus de Brudzewo; c.1445–c.1497) was a Polish astronomer, mathematician, philosopher and diplomat.

Timeline of astronomical maps, catalogs and surveys

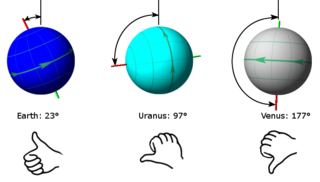

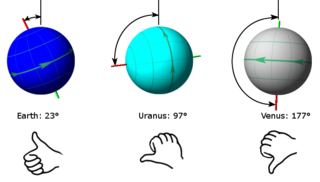

In astronomy, axial tilt, also known as obliquity, is the angle between an object's rotational axis and its orbital axis, which is the line perpendicular to its orbital plane; equivalently, it is the angle between its equatorial plane and orbital plane. It differs from orbital inclination.

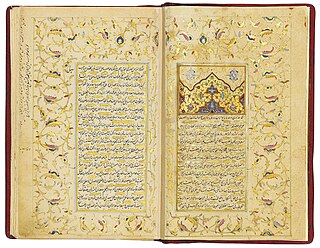

In astronomy and celestial navigation, an ephemeris is a book with tables that gives the trajectory of naturally occurring astronomical objects and artificial satellites in the sky, i.e., the position over time. Historically, positions were given as printed tables of values, given at regular intervals of date and time. The calculation of these tables was one of the first applications of mechanical computers. Modern ephemerides are often provided in electronic form. However, printed ephemerides are still produced, as they are useful when computational devices are not available.

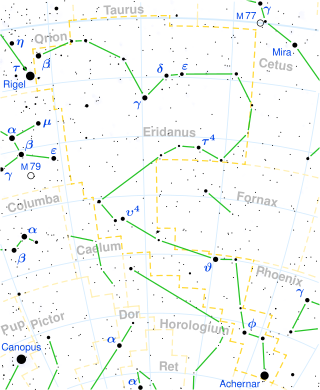

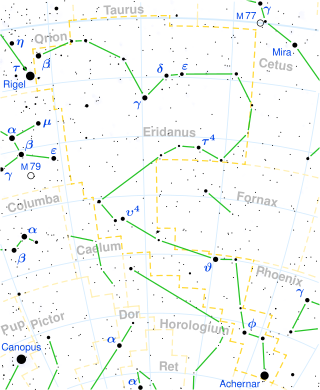

Epsilon Eridani, proper name Ran, is a star in the southern constellation of Eridanus. At a declination of −9.46°, it is visible from most of Earth's surface. Located at a distance 10.5 light-years from the Sun, it has an apparent magnitude of 3.73, making it the third-closest individual star visible to the naked eye.

The Constantinople observatory of Taqi ad-Din, founded in Constantinople by Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf in 1577, was one of the largest astronomical observatories in the pre-modern world. However, it only existed for a few years and was destroyed in 1580.

Abu Jafar Muhammad ibn Husayn Khazin, also called Al-Khazin, was an Iranian Muslim astronomer and mathematician from Khorasan. He worked on both astronomy and number theory.

Medieval Islamic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age, and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in the Middle East, Central Asia, Al-Andalus, and North Africa, and later in the Far East and India. It closely parallels the genesis of other Islamic sciences in its assimilation of foreign material and the amalgamation of the disparate elements of that material to create a science with Islamic characteristics. These included Greek, Sassanid, and Indian works in particular, which were translated and built upon.

Ghiyāth al-Dīn Jamshīd Masʿūd al-Kāshī was an astronomer and mathematician during the reign of Tamerlane.

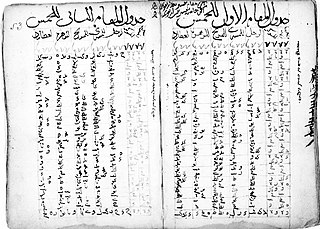

A zij is an Islamic astronomical book that tabulates parameters used for astronomical calculations of the positions of the sun, moon, stars, and planets.

Qāḍī Zāda al-Rūmī, whose actual name was Salah al-Din Musa Pasha, was a Turkish astronomer and mathematician who worked at the observatory in Samarkand. He computed sin 1° to an accuracy of 10−12.

Abdal Ali ibn Muhammad ibn Husayn Birjandi was a prominent 16th-century Persian astronomer, mathematician and physicist who lived in Birjand.

Ala al-Dīn Ali ibn Muhammed, known as Ali Qushji was a Timurid theologian, jurist, astronomer, mathematician and physicist, who settled in the Ottoman Empire some time before 1472. As a disciple of Ulugh Beg, he is best known for the development of astronomical physics independent from natural philosophy, and for providing empirical evidence for the Earth's rotation in his treatise, Concerning the Supposed Dependence of Astronomy upon Philosophy. In addition to his contributions to Ulugh Beg's famous work Zij-i-Sultani and to the founding of Sahn-ı Seman Medrese, one of the first centers for the study of various traditional Islamic sciences in the Ottoman Empire, Ali Kuşçu was also the author of several scientific works and textbooks on astronomy.

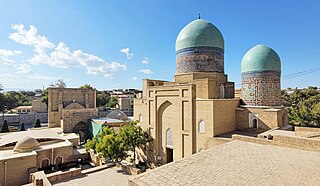

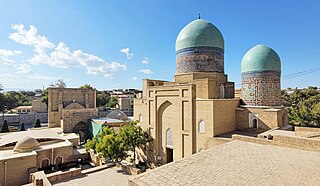

The Ulugh Beg Observatory is an observatory in modern day Samarkand, Uzbekistan, which was built in the 1420s by the Timurid astronomer Ulugh Beg. This school of astronomy was constructed under the Timurid Empire, and was the last of its kind from the Islamic Medieval period. Islamic astronomers who worked at the observatory include Jamshid al-Kashi, Ali Qushji, and Ulugh Beg himself. The observatory was destroyed in 1449 and rediscovered in 1908.

Abu Ali al-Hassan al-Marrakushi was a Magreb astronomer and mathematician from the Kingdom of Morocco. He was especially important in the field of trigonometry and practical astronomy. He wrote Jāmiʿ al-mabādiʾ wa’l-ghāyāt fī ʿilm al-mīqāt, a treatise on spherical astronomy and astronomical instruments. The first part was translated into French by the orientalist and astronomer Jean Jacques Emmanuel Sédillot during the early 19th century, and published after Sédillot's death.

Louis-Pierre-Eugène Amélie Sédillot, was a French orientalist and historian of science and mathematics.

The Timurid Renaissance was a historical period in Asian and Islamic history spanning the late 14th, the 15th, and the early 16th centuries. Following the gradual downturn of the Islamic Golden Age, the Timurid Empire, based in Central Asia ruled by the Timurid dynasty, witnessed the revival of arts and sciences. Its movement spread across the Muslim world. The French word renaissance means "rebirth", and defines a period as one of cultural revival. The use of the term for the description of this period has raised reservations among scholars, some of whom see it as a swan song of Timurid culture.