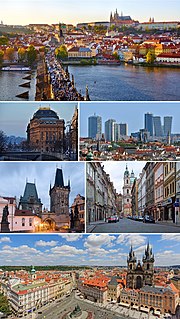

Czechoslovakia, or Czecho-Slovakia, was a sovereign state in Central Europe that existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until its peaceful dissolution into the Czech Republic and Slovakia on 1 January 1993.

The Prague Spring was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in Czechoslovakia as a Communist state after World War II. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), and continued until 21 August 1968, when the Soviet Union and other members of the Warsaw Pact invaded the country to suppress the reforms.

Alexander Dubček was a Slovak politician who served as the First secretary of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) from January 1968 to April 1969. He attempted to reform the communist government during the Prague Spring but was forced to resign following the Warsaw Pact invasion in August 1968.

From the Communist coup d'état in February 1948 to the Velvet Revolution in 1989, Czechoslovakia was ruled by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. The country belonged to the Eastern Bloc and was a member of the Warsaw Pact and of Comecon. During the era of Communist Party rule, thousands of Czechoslovaks faced political persecution for various offences, such as trying to emigrate across the Iron Curtain.

The education system in the former state of Czechoslovakia built on previous provision, which included compulsory education and was adapted in some respects to the ethnic diversity of the region. During the Communist period further progress was made in the school system towards equality in opportunity between regions and genders, but access to higher education depended upon the political compliance of students and their families. After the 'Velvet Revolution' in 1989 many reforms were introduced.

Czechoslovakia, of all the East European countries, entered the postwar era with a relatively balanced social structure and an equitable distribution of resources. Despite some poverty, overall it was a country of relatively well-off workers, small-scale producers, farmers, and a substantial middle class. Nearly half the population was in the middle-income bracket. Ironically, perhaps, it was balanced and relatively prosperous Czechoslovakia that carried nationalization and income redistribution further than any other East European country. By the mid-1960s, the complaint was that leveling had gone too far. Earning differentials between blue-collar and white-collar workers were lower than in any other country in Eastern Europe. Further, equitable income distribution was combined in the late 1970s with relative prosperity. Along with East Germany and Hungary, Czechoslovakia enjoyed one of the highest standards of living of any of the Warsaw Pact countries through the 1980s.

In the history of Czechoslovakia, normalization is a name commonly given to the period following the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 and up to the glasnost era of liberalization that began in the Soviet Union and its neighboring nations in 1987. It was characterized by the restoration of the conditions prevailing before the Prague Spring reform period led by First Secretary Alexander Dubček of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) earlier in 1968 and the subsequent preservation of the new status quo. Some historians date the period from the signing of the Moscow Protocol by Dubček and the other jailed Czechoslovak leaders on August 26, 1968, while others date it from the replacement of Dubček by Gustáv Husák on April 17, 1969, followed by the official normalization policies referred to as Husakism.

The National Front was the coalition of parties which headed the re-established Czechoslovakian government from 1945 to 1948. During the Communist era in Czechoslovakia (1948–1989) it was the vehicle for control of all political and social activity by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ). It was also known in English as the National Front of Czechs and Slovaks.

Although political control of Communist Czechoslovakia was largely monopolized by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) the political power was technically shared with the National Front and openly influenced by the foreign policies of the Soviet Union.

The Constitution of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, promulgated on 11 July 1960 as the constitutional law 100/1960 Sb., was the third constitution of Czechoslovakia, and the second of the Communist era. It replaced the 1948 Ninth-of-May Constitution and was widely changed by the Constitutional Law of Federation in 1968. It was extensively revised after the Velvet Revolution to prune out its Communist character, with a view toward replacing it with a completely new constitution. However, this never took place, and it remained in force until the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1992.

The Constitutional Act on the Czechoslovak Federation was a constitutional law in Czechoslovakia adopted on 27 October 1968 and in force from 1969 to 1992, by which the unitary Czechoslovak state was turned into a federation.

With the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy at the end of World War I, the independent country of Czechoslovakia was formed as a result of the critical intervention of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, among others.

Ota Šik was a Czech economist and politician. He was the man behind the New Economic Model and was one of the key figures in the Prague Spring.

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic ruled Czechoslovakia from 1948 until 23 April 1990, when the country was under communist rule. Formally known as the Fourth Czechoslovak Republic, it has been regarded as a satellite state of the Soviet Union.

The Action Programme is a political plan, devised by Alexander Dubček and his associates in the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), that was published on April 5, 1968. The program suggested that the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) find its own path towards mature socialism rather than follow the Soviet Union. AP called for the acknowledgment of individual liberties, the introduction of political and economic reforms, and a change in the structure of the nation. In many ways, the document was the basis for Prague Spring and prompted the ensuing Warsaw Pact invasion of the ČSSR in August 1968.

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, officially known as Operation Danube, was a joint invasion of Czechoslovakia by five Warsaw Pact countries – the Soviet Union, Poland, Bulgaria, East Germany and Hungary – on the night of 20–21 August 1968. Approximately 250,000 Warsaw pact troops attacked Czechoslovakia that night, with Romania and Albania refusing to participate. East German forces, except for a small number of specialists, did not participate in the invasion because they were ordered from Moscow not to cross the Czechoslovak border just hours before the invasion. 137 Czechoslovakian civilians were killed and 500 seriously wounded during the occupation.

Czechoslovakism is a concept which underlines reciprocity of the Czechs and the Slovaks. It is best known as an ideology which holds that there is one Czechoslovak nation, though it might also appear as a political program of two nations living in one common state. The climax of Czechoslovakism fell on 1918-1938, when as a one-nation-theory it became the official political doctrine of Czechoslovakia; its best known representative was Tomáš Masaryk. Today Czechoslovakism as political concept or ideology is almost defunct; its remnant is a general sentiment of cultural affinity, present among many Czechs and Slovaks.