| Sonnet 135 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

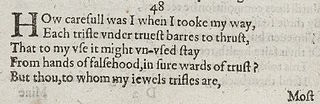

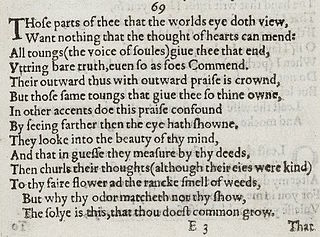

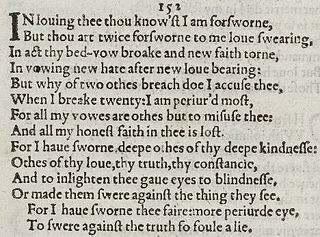

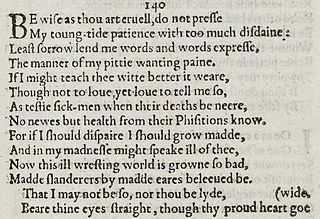

Sonnet 135 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| | |||||||

| |||||||

In Shakespeare's Sonnet 135, the speaker appeals to his mistress after having been rejected by her.

| Sonnet 135 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sonnet 135 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| | |||||||

| |||||||

In Shakespeare's Sonnet 135, the speaker appeals to his mistress after having been rejected by her.

In the first quatrain of the sonnet, the speaker pledges himself to the mistress, while he humbly refers to himself as "I that vex thee." It can be roughly paraphrased as: You have me, and me, and me again.

The second quatrain can be paraphrased thus: Since your will is large and spacious, won't you let me hide my will in yours? Especially since you are graciously accepting others, but not myself?

In the third quatrain, he likens the mistress to an ocean, which would be able to comfortably accommodate an additional quantity of water. Thus, he implicitly gives up the right to an exclusive relationship with the mistress.

There is some debate over the meaning of the final couplet; in her book The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, Helen Vendler supported the interpretation by G. B. Evans (Shakespeare's Sonnets, 1996) as "Let no unkind [persons] kill no fair beseechers."

Sonnet 135 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. Nominally, it follows the rhyme scheme of the form ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, although (unusually) rhymes a, e, and g feature the same sound. It is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 2nd line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / And "Will" to boot, and "Will" in overplus; / × × / × / × / × / More than enough am I that vex thee still, (135.2-3)

The 3rd line (scanned above) features a common metrical variation, an initial reversal; similarly, line 4 has a mid-line reversal. Potentially, line 10 contains an initial reversal, and line 1 a mid-line reversal. Line 8 potentially features a rightward movement of the first ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× × / / × / × / × / And in my will no fair acceptance shine? (135.8)

Lines 4 and 11 also potentially contain minor ionics.

The meter demands a few variant pronunciations: line 5's "spacious" and line 7's "gracious" must each fill out three syllables, while line 11's "being" functions as one. [2]

Counting the contraction wilt as instance of the word will, this sonnet uses the word will a total of fourteen times. Stephen Booth notes "Sonnets 135 and 136 are festivals of verbal ingenuity in which much of the fun derives from the grotesque lengths the speaker goes to for a maximum number and concentration of puns on will." [3] He notes the following meanings used in these two sonnets: [4]

In the 1609 Quarto edition of Sonnets several instances of the word Will capitalized and italicized.

Sonnet 130 is a sonnet by William Shakespeare, published in 1609 as one of his 154 sonnets. It mocks the conventions of the showy and flowery courtly sonnets in its realistic portrayal of his mistress.

Sonnet 48 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Sonnet 49 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Sonnet 51 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is part of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man. It is a continuation of the argument from Sonnet 50.

Shakespeare's Sonnet 69, like many of those nearby in the sequence, expresses extremes of feelings about the beloved subject, who is presented as at once superlative in every way and treacherous or disloyal.

Sonnet 134 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English poet and playwright William Shakespeare. In it, the speaker confronts the Dark Lady after learning that she has seduced the Fair Youth.

Sonnet 152 is a sonnet by William Shakespeare. It is one of a collection of 154 sonnets, dealing with themes such as the passage of time, love, beauty and mortality, first published in a 1609.

Sonnet 150 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is considered a Dark Lady sonnet, as are all from 127 to 152. Nonetheless 150 is an outlier, and in some ways appears to belong more to the Fair Youth.

Sonnet 149 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare.

Sonnet 148 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare.

Sonnet 142 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare.

Sonnet 140 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. Sonnet 140 is one of the Dark Lady sonnets, in which the poet writes to a mysterious woman who rivals the Fair Youth for the poet's affection.

Sonnet 139 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare.

Sonnet 137 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare.

Sonnet 133 is a poem in sonnet form written by William Shakespeare, first published in 1609 in Shakespeare's sonnets.

Sonnet 90 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Sonnet 95 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Sonnet 106 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Sonnet 114 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Shakespeare's sonnet 117 was first published in 1609. It uses similar imagery to Sonnet 116 and expands on the challenge in the closing couplet. Using legally resonant metaphors, the poet defends himself against accusations of ingratitude and infidelity by saying that he was merely testing the constancy of those same things in his friend.