Sonnet 1 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

Sonnet 130 is a sonnet by William Shakespeare, published in 1609 as one of his 154 sonnets. It mocks the conventions of the showy and flowery courtly sonnets in its realistic portrayal of his mistress.

Sonnet 60 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It's a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young beloved.

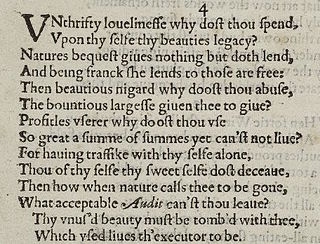

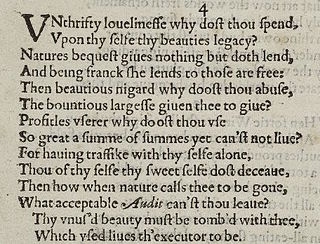

Sonnet 4 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

Sonnet 7 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

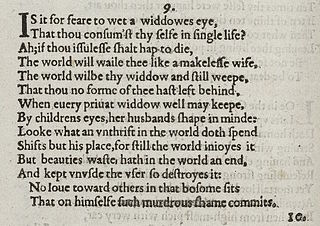

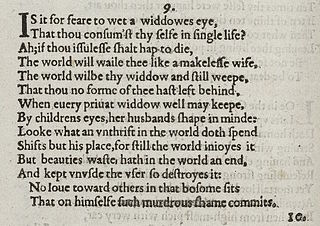

Sonnet 9 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

Sonnet 11 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the 126 sonnets of the Fair Youth sequence, a grouping of Shakespeare's sonnets addressed to an unknown young man. While the order in which the sonnets were composed is undetermined, Sonnet 11 was first published in a collection, the Quarto, alongside Shakespeare's other sonnets in 1609.

Sonnet 15 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It forms a diptych with Sonnet 16, as Sonnet 16 starts with "But...", and is thus fully part of the procreation sonnets, even though it does not contain an encouragement to procreate. The sonnet is within the Fair Youth sequence.

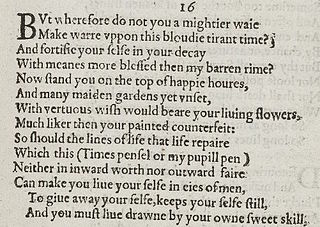

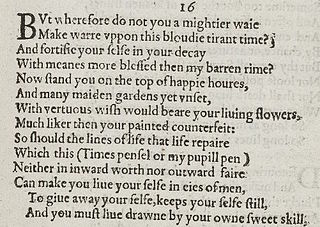

Sonnet 16 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is among those sonnets referred to as the procreation sonnets, within the Fair Youth sequence.

Sonnet 24 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare, and is a part of the Fair Youth sequence.

Sonnet 28 is one of 154 sonnets published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in 1609. It is a part of what is considered the Fair Youth group, and part of another group that focuses on the solitary poet reflecting on his friend. There is a theme of night and sleeplessness, which is a traditional motif that also occurs in Petrarchan sonnets.

William Shakespeare's Sonnet 35 is part of the Fair Youth sequence, commonly agreed to be addressed to a young man; more narrowly, it is part of a sequence running from 33 to 42, in which the speaker considers a sin committed against him by the young man, which the speaker struggles to forgive.

William Shakespeare's sonnet 116 was first published in 1609. Its structure and form are a typical example of the Shakespearean sonnet.

Sonnet 64 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Sonnet 65 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Sonnet 71 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It's a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man. It focuses on the speaker's aging and impending death in relation to his young lover.

Sonnet 136 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare.

Sonnet 127 of Shakespeare's sonnets (1609) is the first of the Dark Lady sequence, called so because the poems make it clear that the speaker's mistress has black hair and eyes and dark skin. In this poem the speaker finds himself attracted to a woman who is not beautiful in the conventional sense, and explains it by declaring that because of cosmetics one can no longer discern between true and false beauties, so that the true beauties have been denigrated and out of favour.

Sonnet 79 is one of 154 sonnets published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in 1609. It is part of the Fair Youth sequence, and the second sonnet of the Rival Poet sequence.

Sonnet 87 is one of 154 sonnets published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in 1609. It is part of the Fair Youth sequence, and sometimes included as the last sonnet in the Rival Poet group.