Sonnet 153 is a sonnet by William Shakespeare.

Sonnet 41 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a part of the Fair Youth section of the sonnets addressed to an unnamed young man. While the exact date of the composition is unknown, it was originally published in the 1609 Quarto along with the rest of the sonnets.

Sonnet 42 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a part of the Fair Youth section of the sonnets addressed to an unnamed young man.

Sonnet 138 is one of the most famous of William Shakespeare's sonnets. Making use of frequent puns, it shows an understanding of the nature of truth and flattery in romantic relationships. The poem has also been argued to be biographical: many scholars have suggested Shakespeare used the poem to discuss his frustrating relationship with the Dark Lady, a frequent subject of many of the sonnets. The poem emphasizes the effects of age and the associated deterioration of beauty, and its effect on a sexual or romantic relationship.

As the last in the famed collection of sonnets written by English poet and playwright William Shakespeare from 1592 to 1598, Sonnet 154 is most often thought of in a pair with the previous sonnet, number 153. As A. L. Rowse states in Shakespeare's Sonnets: The Problems Solved, Sonnets 153 and 154 "are not unsuitably placed as a kind of coda to the Dark Lady Sonnets, to which they relate." Rowse calls attention to the fact that Sonnets 153 and 154 "serve quite well to round off the affair Shakespeare had with Emilia, the woman characterized as the Dark Lady, and the section of the Dark Lady sonnets". Shakespeare used Greek mythology to address love and despair in relationships. The material in Sonnets 153 and 154 has been shown to relate to the six-line epigram ascribed to Marianus Scholasticus in the Greek Anthology. The epigram resembles Sonnets 153 and 154, addressing love and the story of Cupid, the torch, and the Nymph's attempt to extinguish the torch.

Sonnet 56 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man. The exact date of its composition is unknown, it is thought that the Fair Youth sequence was written in the first half of the 1590s and was published with the rest of the sonnets in the 1609 Quarto.

Sonnet 141 is the informal name given to the 141st of William Shakespeare's 154 sonnets. The theme of the sonnet is the discrepancy between the poet's physical senses and wits (intellect) on the one hand and his heart on the other. The "five wits" that are mentioned refer to the mental faculties of common sense, imagination, fantasy, instinct, and memory. The sonnet is one of several in which the poet's heart is infatuated despite what his eyes can see.

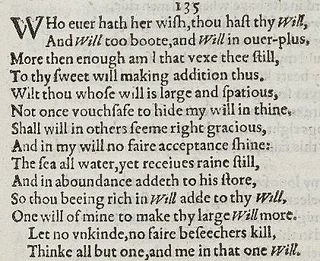

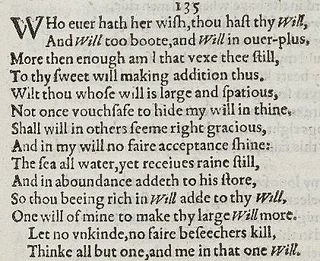

In Shakespeare's Sonnet 135, the speaker appeals to his mistress after having been rejected by her.

Sonnet 134 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English poet and playwright William Shakespeare. In it, the speaker confronts the Dark Lady after learning that she has seduced the Fair Youth.

Sonnet 72 is one of 154 sonnets published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in 1609. It is one of the Fair Youth Sequence, which includes Sonnet 1 through Sonnet 126.

Sonnet 144 was published in the Passionate Pilgrim (1599). Shortly before this, Francis Meres referred to Shakespeare's Sonnets in his handbook of Elizabethan poetry, Palladis Tamia, or Wit's Treasurie, published in 1598, which was frequently talked about in the literary centers of London taverns. Shakespeare's sonnets are mostly addressed to a young man, but the chief subject of Sonnet 127 through Sonnet 152 is the "dark lady". Several sonnets portray a conflicted relationship between the speaker, the "dark lady" and the young man. Sonnet 144 is one of the most prominent sonnets to address this conflict.

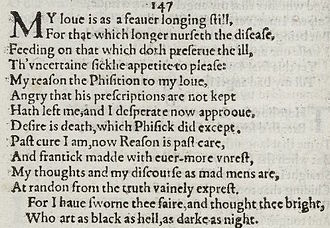

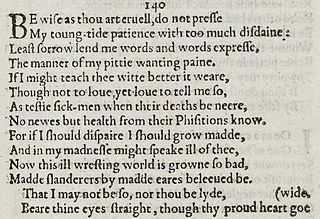

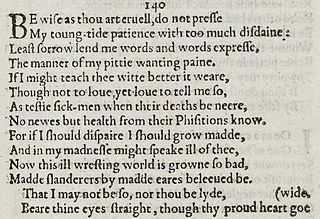

Sonnet 140 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. Sonnet 140 is one of the Dark Lady sonnets, in which the poet writes to a mysterious woman who rivals the Fair Youth for the poet's affection.

Sonnet 136 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare.

Sonnet 133 is a poem in sonnet form written by William Shakespeare, first published in 1609 in Shakespeare's sonnets.

Sonnet 129 is one of the 154 sonnets written by William Shakespeare and published in the 1609 Quarto. It is considered one of the "Dark Lady" sonnets (127–152).

Sonnet 127 of Shakespeare's sonnets (1609) is the first of the Dark Lady sequence, called so because the poems make it clear that the speaker's mistress has black hair and eyes and dark skin. In this poem the speaker finds himself attracted to a woman who is not beautiful in the conventional sense, and explains it by declaring that because of cosmetics one can no longer discern between true and false beauties, so that the true beauties have been denigrated and out of favour.

Sonnet 84 is one of 154 sonnets published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in 1609. It's part of the Fair Youth sequence, and the seventh sonnet of the Rival Poet group.

Sonnet 86 is one of 154 sonnets first published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in the Quarto of 1609. It is the final poem of the Rival Poet group of the Fair Youth sonnets in which Shakespeare writes about an unnamed young man and a rival poet competing for the youth's favor. Though the exact date of its composition is unknown, it has been suggested that the Rival Poet series may have been written between 1598 and 1600.

Sonnet 101 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man. The three other internal sequences include the procreation sonnets (1–17), the Rival Poet sequence (78–86) and the Dark Lady sequence (127–154). While the exact date of composition of Sonnet 101 is unknown, scholars generally agree that the group of Sonnets 61–103 was written mainly in the first half of the 1590s and was not revised before being published with the complete sequence of sonnets in the 1609 Quarto.

Sonnet 102 is one of the 154 sonnets written by English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is one of the Fair Youth sonnets, in which Shakespeare writes of an unnamed youth with whom the poet is enamored. Sonnet 102 is among a series of seemingly connected sonnets, from Sonnet 100 to Sonnet 103, in which the poet speaks of a silence between his Muse and himself. The exact date of writing is unknown, and there is contention among scholars about when they were written. Paul Hammond among other scholars believes that sonnets 61-103 were written primarily during the early 1590s, and then being edited or added to later, during the early 1600s (decade). Regardless of date of writing, it was published later along with the rest of the sonnets of the 1609 Quarto.