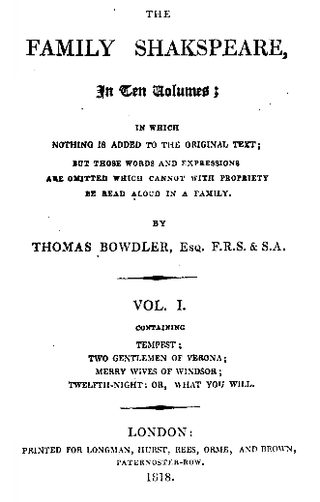

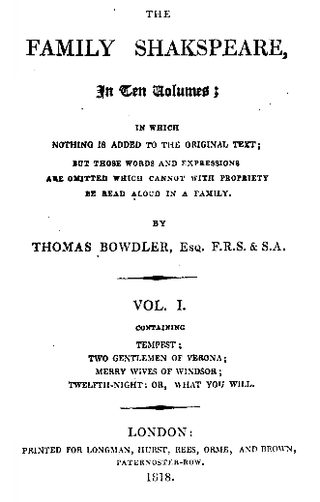

Thomas Bowdler, LRCP, FRS was an English physician known for publishing The Family Shakespeare, an expurgated edition of William Shakespeare's plays edited by his sister Henrietta Maria Bowdler. The two sought a version they saw as more appropriate than the original for 19th-century women and children. Bowdler also published works reflecting an interested knowledge of continental Europe. His last work was an expurgation of Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published posthumously in 1826 under the supervision of his nephew and biographer, Thomas Bowdler the Younger. From his name derives the eponym verb bowdlerise or bowdlerize, meaning to expurgate or to censor something through the omission of elements deemed unsuited to children in literature and films and on television.

William Shakespeare was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon". His extant works, including collaborations, consist of some 39 plays, 154 sonnets, three long narrative poems and a few other verses, some of uncertain authorship. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright. Shakespeare remains arguably the most influential writer in the English language, and his works continue to be studied and reinterpreted.

Cymbeline, also known as The Tragedie of Cymbeline or Cymbeline, King of Britain, is a play by William Shakespeare set in Ancient Britain and based on legends that formed part of the Matter of Britain concerning the early historical Celtic British King Cunobeline. Although it is listed as a tragedy in the First Folio, modern critics often classify Cymbeline as a romance or even a comedy. Like Othello and The Winter's Tale, it deals with the themes of innocence and jealousy. While the precise date of composition remains unknown, the play was certainly produced as early as 1611.

Robert Browning was an English poet and playwright whose dramatic monologues put him high among the Victorian poets. He was noted for irony, characterization, dark humour, social commentary, historical settings and challenging vocabulary and syntax.

David Garrick was an English actor, playwright, theatre manager and producer who influenced nearly all aspects of European theatrical practice throughout the 18th century, and was a pupil and friend of Samuel Johnson. He appeared in several amateur theatricals, and with his appearance in the title role of Shakespeare's Richard III, audiences and managers began to take notice.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1741.

The Parnassus plays are three satiric comedies, or full-length academic dramas, each divided into five acts. They date from between 1598 and 1602. They were performed in London by students for an audience of students as part of the Christmas festivities of St John's College at Cambridge University. It is not known who wrote them.

In his own time, William Shakespeare (1564–1616) was rated as merely one among many talented playwrights and poets, but since the late 17th century has been considered the supreme playwright and poet of the English language.

Victorian literature is English literature during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901). The 19th century is considered by some the Golden Age of English Literature, especially for British novels. In the Victorian era, the novel became the leading literary genre in English. English writing from this era reflects the major transformations in most aspects of English life, from scientific, economic, and technological advances to changes in class structures and the role of religion in society. The number of new novels published each year increased from 100 at the start of the period to 1000 by the end of it. Famous novelists from this period include Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, the three Brontë sisters, Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, and Rudyard Kipling.

English literature is literature written in the English language from the English-speaking world. The English language has developed over more than 1,400 years. The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian dialects brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon invaders in the fifth century, are called Old English. Beowulf is the most famous work in Old English. Despite being set in Scandinavia, it has achieved national epic status in England. However, following the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the written form of the Anglo-Saxon language became less common. Under the influence of the new aristocracy, French became the standard language of courts, parliament, and polite society. The English spoken after the Normans came is known as Middle English. This form of English lasted until the 1470s, when the Chancery Standard, a London-based form of English, became widespread. Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400), author of The Canterbury Tales, was a significant figure developing the legitimacy of vernacular Middle English at a time when the dominant literary languages in England were still French and Latin. The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439 also helped to standardise the language, as did the King James Bible (1611), and the Great Vowel Shift.

William Shakespeare has been commemorated in a number of different statues and memorials around the world, notably his funerary monument in Stratford-upon-Avon ; a statue in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey, London, designed by William Kent and executed by Peter Scheemakers (1740); and a statue in New York's Central Park by John Quincy Adams Ward (1872).

"Don't throw the baby out with the bathwater" is an idiomatic expression for an avoidable error in which something good or of value is eliminated when trying to get rid of something unwanted.

Note: In compliance with the accepted terminology used within the Shakespeare authorship question, this article uses the term "Stratfordian" to refer to the position that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon was the primary author of the plays and poems traditionally attributed to him. The term "anti-Stratfordian" is used to refer to the theory that some other author, or authors, wrote the works.

On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History is a book by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, published by James Fraser, London, in 1841. It is a collection of six lectures given in May 1840 about prominent historical figures. It lays out Carlyle's belief in the importance of heroic leadership.

The Shakespeare Jubilee was staged in Stratford-upon-Avon between 6 and 8 September 1769. The jubilee was organised by the actor and theatre manager David Garrick to celebrate the Jubilee of the birth of William Shakespeare. It had a major impact on the rising tide of bardolatry that led to Shakespeare's becoming established as the English national poet. Thomas Arne composed the song Soft Flowing Avon for the Jubilee.

The spelling of William Shakespeare's name has varied over time. It was not consistently spelled any single way during his lifetime, in manuscript or in printed form. After his death the name was spelled variously by editors of his work, and the spelling was not fixed until well into the 20th century.

The Shakespeare authorship question is the argument that someone other than William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the works attributed to him. Anti-Stratfordians—a collective term for adherents of the various alternative-authorship theories—believe that Shakespeare of Stratford was a front to shield the identity of the real author or authors, who for some reason—usually social rank, state security, or gender—did not want or could not accept public credit. Although the idea has attracted much public interest, all but a few Shakespeare scholars and literary historians consider it a fringe theory, and for the most part acknowledge it only to rebut or disparage the claims.

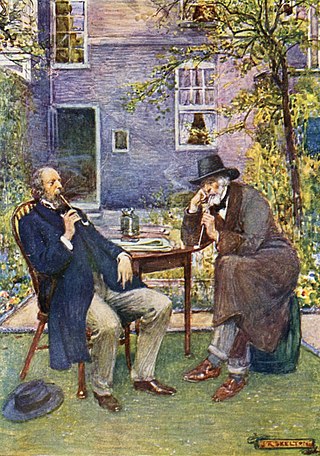

Garrick's Temple to Shakespeare is a small garden folly erected in 1756 on the north bank of the River Thames at Hampton in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Grade I listed, it was built by the actor David Garrick to honour the playwright William Shakespeare, whose plays Garrick performed to great acclaim throughout his career. During his lifetime Garrick used it to house his extensive collection of Shakespearean relics and for entertaining his family and guests. It passed through a succession of owners until coming into public ownership in the 1930s, but it had fallen into serious disrepair by the end of the 20th century. After a campaign supported by distinguished actors and donations from the National Lottery's "good causes" fund, it was restored in the late 1990s and reopened to the public as a museum and memorial to the life and career of Garrick. It is reputedly the world's only shrine to Shakespeare.

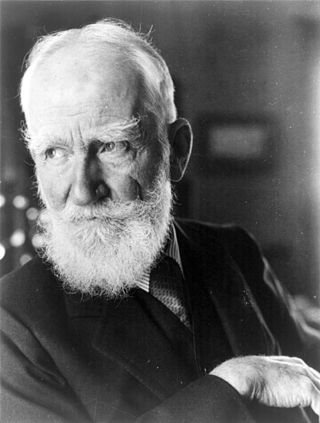

Cymbeline Refinished (1937) is a play-fragment by George Bernard Shaw in which he writes a new final act to Shakespeare's play Cymbeline. The drama follows from Shaw's longstanding need to reimagine Shakespeare's work, epitomised by his play Caesar and Cleopatra and his late squib Shakes versus Shav.

The Shakespeare Ladies Club refers to a group of upper class and aristocratic women who petitioned the London theatres to produce William Shakespeare's plays during the 1730s. In the 1700s they were referred to as "the Ladies of the Shakespear’s Club," or even more simply as "Ladies of Quality," or "the Ladies." Known members of the Shakespeare Ladies Club include Susanna Ashley-Cooper, Elizabeth Boyd, and Mary Cowper. The Shakespeare Ladies Club was responsible for getting the highest percentage of Shakespeare plays produced in London during a single season in the eighteenth century; as a result they were celebrated by their contemporaries as being responsible for making Shakespeare popular again.