Related Research Articles

Ad hominem, short for argumentum ad hominem, refers to several types of arguments, most of which are fallacious. Typically this term refers to a rhetorical strategy where the speaker attacks the character, motive, or some other attribute of the person making an argument rather than attacking the substance of the argument itself. This avoids genuine debate by creating a personal attack as a diversion often using a totally irrelevant, but often highly charged attribute of the opponent's character or background. The most common form of this fallacy is "A" makes a claim of "fact," to which "B" asserts that "A" has a personal trait, quality or physical attribute that is repugnant thereby going entirely off-topic, and hence "B" concludes that "A" has their "fact" wrong -without ever addressing the point of the debate.

A fallacy, also known as paralogia in modern psychology, is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning in the construction of an argument that may appear to be well-reasoned if unnoticed. The term was introduced in the Western intellectual tradition by the Aristotelian De Sophisticis Elenchis.

A fact is a true datum about one or more aspects of a circumstance. Standard reference works are often used to check facts. Scientific facts are verified by repeatable careful observation or measurement by experiments or other means.

The genetic fallacy is a fallacy of irrelevance in which arguments or information are dismissed or validated based solely on their source of origin rather than their content. In other words, a claim is ignored or given credibility based on its source rather than the claim itself.

Inductive reasoning is a method of reasoning in which a general principle is derived from a body of observations. It consists of making broad generalizations based on specific observations. Inductive reasoning is distinct from deductive reasoning, where the conclusion of a deductive argument is certain given the premises are correct; in contrast, the truth of the conclusion of an inductive argument is probable, based upon the evidence given.

An etymological fallacy is an argument that a word is defined by its etymology, and that its customary usage is therefore incorrect.

The Svātantrika–Prāsaṅgika distinction is a doctrinal distinction made within Tibetan Buddhism between two stances regarding the use of logic and the meaning of conventional truth within the presentation of Madhyamaka.

Proof by assertion, sometimes informally referred to as proof by repeated assertion, is an informal fallacy in which a proposition is repeatedly restated regardless of contradiction and refutation. The proposition can sometimes be repeated until any challenges or opposition cease, letting the proponent assert it as fact, and solely due to a lack of challengers. In other cases, its repetition may be cited as evidence of its truth, in a variant of the appeal to authority or appeal to belief fallacies.

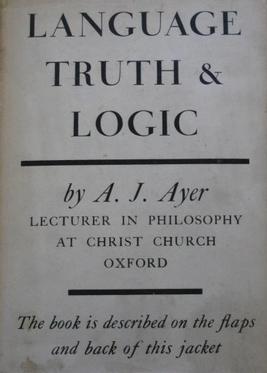

Language, Truth and Logic is a 1936 book about meaning by the philosopher Alfred Jules Ayer, in which the author defines, explains, and argues for the verification principle of logical positivism, sometimes referred to as the criterion of significance or criterion of meaning. Ayer explains how the principle of verifiability may be applied to the problems of philosophy. Language, Truth and Logic brought some of the ideas of the Vienna Circle and the logical empiricists to the attention of the English-speaking world.

Logic is the formal science of using reason and is considered a branch of both philosophy and mathematics and to a lesser extent computer science. Logic investigates and classifies the structure of statements and arguments, both through the study of formal systems of inference and the study of arguments in natural language. The scope of logic can therefore be very large, ranging from core topics such as the study of fallacies and paradoxes, to specialized analyses of reasoning such as probability, correct reasoning, and arguments involving causality. One of the aims of logic is to identify the correct and incorrect inferences. Logicians study the criteria for the evaluation of arguments.

The analytic–synthetic distinction is a semantic distinction used primarily in philosophy to distinguish between propositions that are of two types: analytic propositions and synthetic propositions. Analytic propositions are true or not true solely by virtue of their meaning, whereas synthetic propositions' truth, if any, derives from how their meaning relates to the world.

Persuasive writing is a form of written communication intended to convince or influence readers to accept a particular idea or opinion and to inspire action. A wide variety of writings, such as criticisms, reviews, reaction papers, editorials, proposals, advertisements, and brochures, utilize different persuasion techniques to influence readers. Persuasive writing can also be employed in indoctrination. It is often confused with opinion writing; however, while both may share similar themes, persuasive writing is backed by facts, whereas opinion writing is supported by emotions.

Appeal to the stone, also known as argumentum ad lapidem, is a logical fallacy that dismisses an argument as untrue or absurd. The dismissal is made by stating or reiterating that the argument is absurd, without providing further argumentation. This theory is closely tied to proof by assertion due to the lack of evidence behind the statement and its attempt to persuade without providing any evidence.

The Principle of Nonvacuous Contrast is a conceptual framework and methodological principle that holds significance within various fields such as philosophy, science, linguistics, and epistemology. This principle is fundamentally rooted in the idea that meaningful distinctions and assertions can only be formulated and comprehended when there exists a clear and discernible contrast between different concepts or entities. The principle plays a pivotal role in shaping logical reasoning, meaningful communication, and the establishment of knowledge.

Buddhist logico-epistemology is a term used in Western scholarship to describe Buddhist systems of pramāṇa-vāda and hetu-vidya. Pramāṇa-vāda is an epistemological study of the nature of knowledge; Hetu-vidya is a system of logic. These models developed in India during the 5th through 7th centuries.

The psychology of reasoning is the study of how people reason, often broadly defined as the process of drawing conclusions to inform how people solve problems and make decisions. It overlaps with psychology, philosophy, linguistics, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, logic, and probability theory.

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It studies how conclusions follow from premises due to the structure of arguments alone, independent of their topic and content. Informal logic is associated with informal fallacies, critical thinking, and argumentation theory. It examines arguments expressed in natural language while formal logic uses formal language. When used as a countable noun, the term "a logic" refers to a logical formal system that articulates a proof system. Logic plays a central role in many fields, such as philosophy, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics.

A tone argument is a type of ad hominem aimed at the tone of an argument instead of its factual or logical content in order to dismiss a person's argument. Ignoring the truth or falsity of a statement, a tone argument instead focuses on the emotion with which it is expressed. This is a logical fallacy because a person can be angry while still being rational. Nonetheless, a tone argument may be useful when responding to a statement that itself does not have rational content, such as an appeal to emotion.

References

- 1 2 "Specious Reasoning: How to Spot It and Stop It | Psychology Today". Psychology Today . Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ↑ "On the Origin of Specious Arguments". American Scientist. 2017-02-06. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- ↑ "Sophism | argument | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ↑ "specious | Etymology, origin and meaning of specious by etymonline". Online Etymology Dictionary . Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ↑ "Research vindicates £350m/week claim on side of Big Red Brexit Bus". facts4eu.org. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ↑ Crisp, James (2019-05-16). "Jean-Claude Juncker says £350m bus slogan was a lie as deputy calls Brexit Britain 'Game of Thrones on steroids'". The Telegraph . ISSN 0307-1235 . Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ↑ Cowen, P (1999-12-18). "The price of coffins: specious arguments by eminent doctors against the dangers of tobacco". British Medical Journal . 319 (7225): 1621–1623. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1621. PMC 1127088 . PMID 10600970.

- ↑ Hasan, Mehdi (2023-02-16). "How to Beat Trump in a Debate". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- ↑ "Gish Gallop: When People Try to Win Debates by Using Overwhelming Nonsense – Effectiviology" . Retrieved 2023-07-28.